During the July 23 CNN/YouTube Democratic presidential debate, Hillary Clinton was asked if she would describe herself as a liberal. A serious enough question you might say, but the audience laughed. Why? Mainly, I think, because “liberal” has long been such an effective political pejorative we can hardly imagine a major presidential contender embracing the label. The laughter anticipated an almost certain evasion. How will she wiggle out of this one?

“It is a word that originally meant that you were for freedom,” Clinton responded. Fair enough. Back in the 19th century, liberals championed individual rights, limited government, and the freedom of capitalists to operate without regulation—closer to the libertarians of today. “Unfortunately,” Clinton added, “in the last 30, 40 years [liberal] has been turned up on its head and it’s been made to seem as though it is a word that describes big government.”

Actually, it’s been “made to seem” a lot more than that. The caricatures of liberals glibly dispensed by Fox News and Ann Coulter may not represent a majority view, but they date back at least as far as Ronald Reagan’s presidency and have helped make the word such a nasty and distorted epithet that any rebuttal is almost guaranteed to sound incomplete and defensive. We’ve all heard some version of the charge that liberals are elitist, unpatriotic, blame-America-first appeasers who support gays, prisoners, terrorists, illegal aliens, and abortionists while happily raising taxes on hard-working, church-going, “average” Americans to bankroll ever larger and more inefficient government bureaucracies.

No wonder Clinton wouldn’t even utter the “L”-word. “I prefer the word ‘progressive,’” she said, “someone who believes strongly in individual rights” and “working together” to “find ways to help those who may not have all the advantages in life to get the tools they need to lead a more productive life.” “Working together” sounds appealing, but offers no guidance on the specific role of government. And while Clinton identified herself with the progressives of the early 20th century she did not remind us that those reformers and the New Deal/Great Society liberals of the 1930s and 1960s believed the federal government had a responsibility to check corporate wrong-doing and provide some assistance to (among others) military veterans, the elderly, the unemployed, and the poor. The basic idea of 20th century liberalism was that government should intervene to remediate capitalism’s grossest failures and the failures of local authorities to protect constitutional rights. Liberalism was not an endorsement of “big government” for its own sake, but a claim that government is crucial to social and economic stability and the promotion of a more humane society.

During the high water mark of liberalism in the mid-1960s, many Democrats and a fair number of Republicans proudly called themselves liberals and routinely took credit for virtually every landmark reform from the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Perhaps an unabashed defense of liberalism is just what the doctor ordered. That, at least, is the aim of recent work like historian Kevin Mattson’s When America Was Great: The Fighting Faith of Postwar Liberalism (Routledge, 2006) Mattson sets out to buff up the reputations of once famous liberal icons such as Arthur Schlesinger, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Adlai Stevenson.

Projects like this may achieve a worthy political end—demonstrating that liberals have a significantly better record representing the interests of most Americans than conservatives. But Mattson and others have had difficulty answering the critique of liberalism that came not from conservatives like Goldwater and Reagan, but from political activists in the civil rights movement and New Left of the 1960s. One of their best known criticisms is that liberal anti-Communists were at least as responsible for the disaster of the Vietnam War as their conservative counterparts, a charge that has its counterpart today in criticisms of the Democratic Party for sanctioning the Iraq War and moving too slowly to condemn it.

Perhaps even more significant to the present, the Left of the 1960s attacked liberals for their political timidity, for embracing modest reforms where fundamental change was required. Liberals, they said, were so invested in the status quo they would offer only band-aids to patch gaping wounds. When push came to shove, they would support social order over social justice.

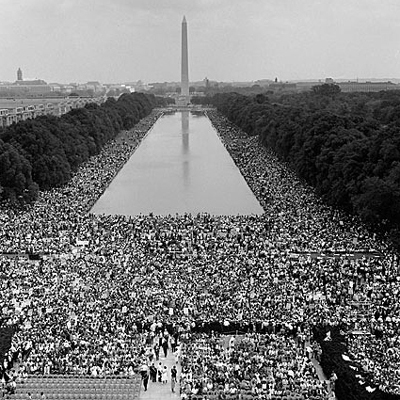

Real change, activists argued, would only come from the political mobilization of ordinary citizens. As Martin Luther King wrote in his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (1963), “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.” Can we recall a significant liberal reform that has not come in response to years of organization and protest by workers, women, blacks, students, or other groups of citizen activists? I can’t.

Yet political leaders rarely acknowledge those movements as central to historical change. To cite only one example, think of Al Gore’s documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. Gore praises a few scientific experts for documenting global warming, but fails to credit the environmental movement for pushing the issue to public attention. Omissions like that reinforce the view that liberal politicians believe only in top-down, expert-controlled, “progressive” reform.

If real change is to come (national health care, for example), the government will have to assert itself in concert with a mobilized public. It’s hard to be optimistic. but here, for me, is a sliver of hope. In one of his standard stump speeches, Barack Obama says the civil rights movement is a celebration not of African American history, but American history, “because at every juncture in American history, that’s how change happens—by people coming together and deciding we’re going to have a better America. . . . change has always happened not from the top down but from the bottom up. And that’s exactly how you and I will change this country.” Obama’s call to “come together” may prove as empty as Hillary Clinton’s “working together,” but if either one has the political courage and conviction to build on a bottom-up understanding of change, we might be led toward an era of liberalism our history of activism deserves.

–Christian Appy, Professor of History, UMass Amherst