In 2001 I traveled across the war-blackened villages of Kosovo and saw first hand the evidence of Serbian atrocities carried out against the region’s indigenous Kosovar Albanian population. All of these horrors had been carried out in blatant disregard for established norms that the US and all civilized countries officially abided by. The world understood that the Serbs were beyond the pale of civilization and NATO forcefully ended their campaign of ethnic cleansing with a UN mandate (resolution 1244).

But try telling the pariah Serbs that. When I returned to London where I was teaching at the time I subsequently met a group of Serbs who were unwilling to accept that their country’s forces had engaged in ethnic cleansing in Kosovo or Bosnia. I remember asking them if they thought the UN and the entire world from Guatemala to Thailand had just imagined their country’s war crimes.

I will always remember one of their replies to my inquiry, “We don’t need the world and don’t believe in their conspiracies against us. They hate us because we are Serbs.”

I recall thinking at the time, “Thank God I’m an American, a citizen of the country that has worked to create global consensus and alliances such as NATO and New York-based UN. My country would never be so perversely dismissive of the rest of the world’s opinion,” I thought at the time.

One thing I thought the US would have learned from the horrible images of Americans falling out of the burning World Trade Centers is that other people’s perceptions of us are not irrelevant. Our need to win over others and burst the bubble of isolation from the rest of the world through alliances was never clearer than on that day.

But in the build-up to the US invasion of Iraq, the magic moment of 9/11 was lost, and with it the hearts and minds of many of our allies and those neutrals we sought to win over. A unilateralist “you are with us or against us” mood swept the country as we surveyed the world with newfound distrust. Convinced of the uniqueness of our victimhood and infallible righteousness of our struggle, dissenting opinion from historic allies came to be defined as a betrayal.

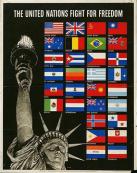

When the UN (which many in the Middle East have long accused of being a US tool), dared to suggest that it had uncovered no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, it was seen as being “against us.” When the French (the same ones who sent troops to Afghanistan and helped us gain independence) expressed similar skepticism of the rationale for invading sovereign Iraq, millions of Americans came to consider France to be an archenemy. Turning our back on the UN and NATO allies like Germany, France, Turkey and Belgium that had voted in the UN against our unilateral invasion, we launched Operation Enduring Freedom. The message to our NATO allies, the UN, and the world was clear: we did not need them.

our back on the UN and NATO allies like Germany, France, Turkey and Belgium that had voted in the UN against our unilateral invasion, we launched Operation Enduring Freedom. The message to our NATO allies, the UN, and the world was clear: we did not need them.

Fast forward to September 11, 2007. With over 3,700 dead soldiers in a war that has out-lasted our involvement in World War II, the US-led Coalition (which includes such “powers” as Palau, Micronesia, Tonga, and Eritrea, but is missing the support of such Cold War stalwarts as Germany, France, and Turkey) is desperately in need of allies. We could use the help of our NATO allies who were with us in Afghanistan (Germany, Turkey, France etc) but not in Iraq.

We could also use the blue-helmeted UN soldiers from the Arab world to train the Iraqi security forces and patrol dangerous Iraqi neighborhoods where Americans (who don’t speak Arabic) are defined as “infidels.” And God knows we could use the economic support of the European Union countries, which Donald Rumsfeld contemptuously dismissed as “Old Europe” to help rebuild Iraq. In other words, we could use the sort of international support of the sort we marshaled for the first Gulf War but spurned in the 2003 rush to invade Baathist Iraq.

It is time to put aside the “your against us” rhetoric of the early days of Operation Iraqi Freedom and reach out to such pro-American leaders as France’s new president Sarkozy, to the UN (which was right about the lack of WMDs) and other countries that were "against us" when confronted with our belligerent unilateralism in Iraq.

And John Hill is correct. We must learn from our mistakes. When we reject the criticism of our allies and the very institutions that we helped build to create global consensus, we run the risk of becoming like those Serbs who claimed, “We don’t need the world and don’t believe in their conspiracies against us. They hate us because we are Serbs.”

While the world will always be filled with those who resent us for being on top, we cannot afford to make enemies out of friends. Especially when we are engaged in a two-front war in Iraq and Afghanistan against an enemy our president claims “hates us for our freedom.”

–Brian Glyn Williams, Assistant Professor of Islamic History, UMass Dartmouth