Standing at the empty lot at 686 Main St. in Holyoke, it's easy enough to imagine a trash transfer station at the site.

The land, ringed by a chain-link fence, sits in the city's designated waste management district. On one side of the two-plus acre parcel is Holyoke's wastewater treatment facility; on another side, just across Berkshire Street, is the city's yard-waste drop-off site, where a pile of discarded Christmas trees awaits recycling. The immediate neighborhood is largely industrial in nature, dominated by oil companies, paper companies, printers.

But travel just beyond that ring of buildings and the nature of the neighborhood changes again, to include modest single-family homes, rental properties and the pride of the neighborhood, Springdale Park. Morgan Elementary School is half a mile from the site; Holyoke High and Dean Technical High are both within a mile and a half. It's a fragile neighborhood, one that struggles with high poverty rates, public health problems, language barriers (many residents speak Spanish as their primary language), ailing schools. The last thing it needs, many in the area say, is to add trash into the mix.

But that's what could happen, if a proposal to build a 22,575-square-foot trash transfer station at 686 Main St. succeeds. The project, proposed by United Waste Management, Inc., based in Bolton, Mass., would be a drop-off site for solid municipal waste, collected from neighboring communities, and for construction and demolition, or C&D, waste. The waste would be consolidated and then transported to landfills.

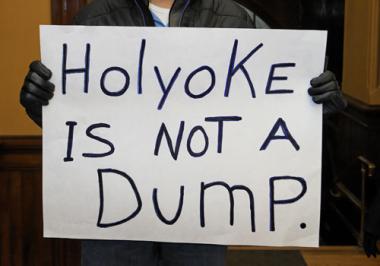

Angry residents are organizing against the project, citing worries about pollution, increased traffic and noise. Proponents of the project counter that the station would bring jobs and tax revenue to a city that could use more of both, and say fears about the project are off the mark.

And while neighbors have the backing of city councilors and a dedicated coalition of activists, they face an uphill battle: Right now, they have little legal standing in their fight to stop the project.

City Councilor Diosdado Lopez has represented Ward 2, which includes the proposed transfer station site, for 17 years. Like other opponents, he says the project snuck up on the neighborhood, with little public notification or opportunity for input.

"This whole project has been like a secret," Lopez says. "Even though I represent the area where the project is being proposed, I never got any information until I found out through the Planning Board. That usually never happens."

But once he got wind of the idea, Lopez lost no time trying to kill it. He and others opposed to the project see numerous potential problems: Pollution, generated by as many as 225 trucks a day, carrying up to 750 tons of trash to the transfer station, in a city where asthma rates are already higher than average. Noise created by the trucks and by train cars, running on tracks adjacent to the site, that would carry some of the trash from the transfer station. The wear and tear on the streets caused by the increased traffic, which they also worry could cause jams that would make it hard for emergency vehicles to get through. Declining property values for homeowners who suddenly find themselves neighbors to a trash drop-off site. Concerns about the materials at the site, including the potential for toxins like asbestos and mercury in the construction and demolition waste.

"It doesn't make sense to put something like this project in the neighborhood," Lopez says. "We don't deserve it, due to all the problems we have in the area."

Last fall, Lopez struck what looked to be a debilitating, if not fatal, blow against the transfer station project: In October, the City Council unanimously approved his proposal for a 12-month moratorium on any new waste processing or trash transfer facilities in the city.

Ginetta Candelario, a Smith College sociology professor who lives in Holyoke's Highlands neighborhood, was one of the residents who came to the council meeting that night, waving signs and wearing medical masks to symbolize their concerns about the health effects of the transfer station. "We left feeling very satisfied that we had managed to at least put the brakes on this project," Candelario recalls.

The victory was short-lived, however; within a week, the city's Law Department declared that the moratorium was not legally valid. In an Oct. 22 letter to Mayor Michael Sullivan, who had requested her opinion on the legality of the moratorium, City Solicitor Karen Betournay wrote that "the order as adopted was not in proper legal form." The moratorium, she wrote, amounted to an amendment of the city's zoning ordinance, but the Council had failed to follow the legal process, including public notice and a hearing, necessary to amend an ordinance. In addition, Betournay cited a Mass. General Law that prohibits municipalities from banning a waste disposal facility on a site already zoned for that use.

The city solicitor did note that the Council could vote to require a transfer station to obtain a special permit imposing conditions on the project. "[I]t is my opinion that a Court would not uphold the [moratorium] order, should United Waste challenge it in Court," Betournay wrote. "Rather than allowing this project to be forced upon the City through the Court system, the City should work with United Waste Management to address residents' concerns during the permitting process."

In light of Betournay's opinion, Sullivan did not sign the moratorium order, effectively vetoing it. Opponents, however, have not given up the fight: Lopez still hopes to legally impose a moratorium; barring that, he hopes to pass an order that would require United Waste Management—or any company looking to open a transfer station or recycling facility in the city—to apply for a special permit. Right now, UWM doesn't need a special permit, since the land is already zoned for waste management.

"If indeed it's going to go in, let it go in with some conditions," Lopez says. That might mean limiting the hours of operation (according to UWM documents about the project, the station would be open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, except for six major holidays a year) or reducing the maximum amount of trash allowed at the site. The permit could also require that the center, which is now pitched as a regional facility, only accept trash from within the city, Lopez suggests. "Holyoke shouldn't be a dump for any other cities or towns," he says.

Holyoke would not, in fact, serve as a dump for other communities; the project proposed for 686 Main St. would be a transfer station, where waste would be dropped off, consolidated, and then sent out to landfills.

But symbolically, opponents—who've formed a group called Holyoke Organized to Protect the Environment, or HOPE—see the project as dumping on an already beleaguered community. "We have not had a real conversation about any of this, and consequently it feels like they're trying to push something through," says Candelario.

A moratorium would create an opportunity for that conversation, she says. "What we basically want is a pause. We want to really assess the costs and benefits of a transfer station, and is this the best location. We don't think it is," she says.

"You're talking about hundreds of tons [of trash] coming in every day," Candelario says. "That's a huge amount of waste coming into the city and, sadly, coming into the ward that has the highest poverty rate, the highest asthma, high diabetes. You're talking about the most vulnerable population in Holyoke … made even more vulnerable."

William Aponte is an environmental organizer with Nuestras Raices ("Our Roots"), a community organization focused on environmental issues and economic development in Holyoke. He's also co-director of an "environmental justice" grant Nuestras Raices received, with Mount Holyoke College, from the federal Environmental Protection Agency to assess the risks posed by toxins in the city and develop community partnerships to address the problem.

"We have many environmental problems here—diesel trucks and buses driving through the community, brownfields and abandoned buildings, the river is contaminated, the outdoor air pollution—you name it," says Aponte.

Adding a transfer station, Aponte says, runs counter to the work his organization is trying to do. "Why can't we focus on the problems we have here and try to find solutions to that, and bring healthy businesses to the community?" he asks. "Why bring a transfer station to a downtown community?"

Candelario agrees. She points to the city's ambitious Canal Walk project, which aims to revitalize the canal district with a pedestrian mall, an "arts corridor," retail and museums. "And three blocks south of there, you're going to have hundreds of dump trucks bringing trash in and out of the city?" she asks. "This is literally the gateway to Main Street." (The transfer station site sits three-quarters of a mile from the southernmost point of the Canal Walk project.)

"Holyoke has enormous potential," Candelario says. "It's a beautiful city. It's got character, architecture and history. And this just seems like a giant step backwards."

Scott Lemay, CEO of United Waste Management, says there are a lot of misconceptions about the transfer station project. That's not unusual; waste management projects tend to trigger people's worst fears, says Lemay, who's been in the industry for more than 20 years.

"People think there's pollution, and you're dumping on them," he says. But, he points out, a transfer station is not a dump or a landfill; it's a place where waste material is temporarily stored while loads brought in by smaller vehicles are consolidated to be carried out by larger trucks or by train. The material is not burned or processed, and it doesn't remain there long enough to decompose, he says.

"The reality is, you're dumping in a closed building," Lemay says. "Everything that goes into the building goes out of the building."

Lemay describes the project as having numerous benefits for the city of Holyoke. "For starters, it will create jobs, good-paying jobs," he says. Lemay estimates the facility would need about eight workers on site, such as heavy equipment and scale operators, in addition to office staff such as accounting personnel and the truck drivers and rail workers who would transport the material. "We definitely will give preference to Holyoke people," he adds.

Another benefit—one that's caught the attention of some in City Hall—is the tax revenue the project would bring to Holyoke. "You have an industrial piece of property there right now that is clearly distressed," Lemay said. Developing the property would bring in property taxes as well as excise taxes on the equipment; while the specifics of the building are still being sorted out, Lemay describes the station as a "multi-million dollar facility" that would yield "hundreds of thousands" in taxes. In addition, he says, United Waste Management is willing to negotiate a "royalty" payment to the city, which is not mandated by law but is standard in the industry for larger-scale projects.

"We're committed to making sure there are benefits to the city," he says.

Lemay contends that many of the community concerns are not as bad as opponents suggest. The facility would generate an average of 150 vehicles trips a day, with a maximum capped at 225. The site's proximity to I-391, he says, means the trucks would not be on city streets for long. And plans to move material from the facility by rail would mean fewer trucks on the road and would make it easier to move the trash to larger regional landfills, to relieve stress on already overburdened landfills in the area.

Lemay says it's unclear yet how many communities would be served by the transfer station, although he says it would serve "the immediate communities. … People would not long-haul waste from far-away communities."

Lemay says he understands residents' fears about the transfer station, especially given the history of the site, which has, at times, hosted an incinerator and a composting site. A transfer station, he says, would not create the same odor and pollution issues.

"People need to realize that this isn't some toxic waste dump," he says. "We're talking about their trash, the surrounding communities' trash. It's no different than what you look at in your waste barrel or in a dumpster out in the city."

The concerns of residents who oppose the transfer station extend beyond environmental and traffic issues to include politics and public process. Some suggest that the project is being pushed through because it's in a heavily poor, mostly Latino neighborhood. "I believe it's like a racial project," says Nuestras Raices' Aponte, who notes that many affected residents speak Spanish as their primary language, which makes it harder for them to be engaged in the public process or to weed through technical documents that are available in English only.

And while the City Council unanimously passed the moratorium last fall, project opponents say that doesn't necessarily mean they've got city government on their side. "The mayor is basically selling this idea that he's neutral, which I don't believe," says Diosdado Lopez, who contends Sullivan is quietly backing the project.

Not so, counters Sullivan. "I really haven't taken any position one way or another," the mayor says. "I try and be fair about the advantages to the city and the disadvantages."

But, Sullivan adds, he also has to make sure the city doesn't overstep its legal rights. He didn't sign the moratorium, he says, because the Law Department made it clear it was not legally sound. He says he also has to keep in mind that, as things now stand, UWM has a legal right to build the transfer station, since the land is already zoned for that use.

"We also are very cognizant and very aware of people's land rights, and the process. This is privately held land. Taking a position one way or another would be imprudent, because that's how litigation starts," Sullivan says. "If United Waste thinks that it's unfair to them one way or another, or the residents do, it may lay the ground for a suit down the road."

While Sullivan says he's not taking a position on the project, he appears to consider its building a likely possibility and is already considering ways to mitigate potential problems. "Certainly, there are concerns," the mayor says, pointing, for instance, to increased traffic in the area. But, he says, the project might be an opportunity to get UWM to help improve traffic flow in the neighborhood, especially at I-391.

"The city engineer and I don't feel [the traffic concerns are] insurmountable, and we feel there probably would be a benefit for the greater good if we could make improvements in that area," says Sullivan. Plus, he adds, a local transfer station would mean fewer trucks heading through the city to the West Springfield facility where Holyoke now sends its trash—provided the city contracts with UWM to handle its trash.

After discussions with Lemay and with the city's DPW head, Sullivan feels many neighborhood fears about the project are unfounded. "From an environmental aspect, there's a lot of misinformation out there," he says. UWM would have control systems to handle dust and odor, he says, and the trash sorting would all take place within the building. "That's far better than what we had there before, which was an odorous nightmare," says Sullivan, referring to the former composting facility.

Sullivan objects to suggestions that Ward 2 is being treated unfairly, and that the project would never happen in a more affluent neighborhood. The fact is, he says, the project is targeting this community because it's already zoned for waste management.

"Every neighborhood has to put up with some aspect of quality of life," says Sullivan. People in the Ingleside area are bothered by mall traffic; residents of West Holyoke complain about snowmobilers; in the Highlands, they're unhappy about the coal-burning plant and the Mount Tom quarry. Given a choice, "they'd probably take the transfer station," Sullivan says.

"People don't like these things," he says of the transfer station. "They need them, but they don't like them."

One other thing Holyoke needs, the mayor adds, is revenue. While he doesn't yet know how much the transfer station would generate in taxes, he says, "I think it's safe to say it would be more than [the property] does now." The project could generate other income for the city, too, such as tipping fees.

"That money is going to go to our schools, our police, our fire. Like every community, we're starving to find new sources of revenue," Sullivan says. He even raises the specter of something that has caused much turmoil in Holyoke's biggest neighbor to the south: "I'm not saying it will, but this project may be the difference between Holyoke continuing to have free trash pick-up and having a fee like Springfield does."

Freshman City Councilor Rebecca Lisi wasn't in office when the moratorium was passed last fall. But she supports Lopez's new moratorium effort, to allow the city and residents time to evaluate the project and to make sure there's a fair process in place for evaluating such proposals in the future.

If the moratorium fails, Lisi supports requiring transfer stations to get a special permit from the City Council. "In the end, the special permit is a fallback. As a last resort, the special permitting process is there to make sure it's not interfering with the lives of the residents," she says. "It's reasonable to impose conditions about things like hours, noise control and traffic control."

Transfer stations can have positive benefits, such as encouraging recycling, says Lisi. But, she asks, "Is this the place to put it? … No one puts a transfer station on Main Street USA."

She adds: "I definitely sympathize with [Lemay] on a few points—there's a lot of misunderstanding about what a transfer station is. But it's his responsibility to communicate with residents and make clear his proposal."

That, Lemay says, is what he was doing at a public hearing last month on the special permit and moratorium proposals. (That heavily attended hearing was continued to Feb 26, at 6:30 p.m. in City Hall.) At the hearing, Lemay spoke out against a special permit, which he says is redundant, given the numerous requirements already imposed at multiple levels: The state Department of Environmental Protection has an extensive review process for such projects, and UWM would also need the OK of several city bodies, including the Board of Health and the Building and Fire Departments. "There already is a very well-detailed, scrutinized process," Lemay says.

UWM, he adds, is willing to work with the city to address public concerns. "We want this project to create benefits for the community," Lemay says. "To the extent that an issue comes up that we feel needs to be compromised, we're open to discussion. …

"We intend to have a very, very open process. We're proud of the things that we do. We want the people to have the information," adds Lemay, whose company details its proposal on a website: www.uwmholyoke.com.

Lemay believes city residents are starting to feel more comfortable with the project. "We're starting to open people's eyes," he says. "I think people that weren't that receptive in the past are starting to talk about the issues more, as opposed to just being against it."

But not everyone is ready to get on board with the project—starting with Diosdado Lopez. In addition to the special permit and moratorium proposals, he's also looking into other ways the city might stop the project, such as refusing UWM an easement to the property. He's also working with HOPE to consider other recourses, including raising money for a legal fight. "I'm hoping we don't let this guy go in without a fight to the end, even if we have to go to court," Lopez says. The group is also considering splashier tactics, such as picketing outside Lemay's home in eastern Mass., the councilor adds.

"This is a big project for the neighborhood, and I haven't found any support in the neighborhood," Lopez says. "With this project, we're going back 20 years."

—mturner@valleyadvocate.com