Amongst Zen Buddhist lore, there is a mendicant monk who goes from village to village collecting useless things. He hauls them in a large cloth sack, wherefore his name, Hotei, meaning “cloth bag.” When he comes around, children follow him. When he sees ones who shine, he gifts them with objects from the bag. The adults shake their heads, but the children run off, delighted: riding an imagined horse, sailing a ship, bearing a crown, and heads full of ideas.

Amongst Zen Buddhist lore, there is a mendicant monk who goes from village to village collecting useless things. He hauls them in a large cloth sack, wherefore his name, Hotei, meaning “cloth bag.” When he comes around, children follow him. When he sees ones who shine, he gifts them with objects from the bag. The adults shake their heads, but the children run off, delighted: riding an imagined horse, sailing a ship, bearing a crown, and heads full of ideas.

Artists find Hotei appealing. He is often shown, arms raised, singing or laughing at the moon. The bag on the ground is often painted with the same perfect circular brushstroke that depicts the moon. It is as though it is imbued with a share of the lunar power. Maybe artists see there their own moments of inspiration, and themselves as equivalent transformers of shamanic powers.

In the actual art making though, those initial lunatic flashes are often fleeting. Substantive work is most likely to come from subsequent heavy hauling. The true magical transformation, in fact, is at that second moment: when the art is passed on, perceived and received. The viewer, then, becomes the active co-creator of the art. Hotei passes it on to the children, some artists like to pass it on to discerning collectors, some struggle and are glad to touch a handful, and others, choose to give voice to those without much voice – satisfactory all. I am more of the last, and can speak most from there.

Several years ago, I was asked to do a public art piece in Yakima, Washington to help bring together its various people: European descendants, Yakama Indians and Mexican and other immigrants. As representatives from the groups discussed, the marker became a 6,500-sq.ft. sculptural plaza, in the city‘s downtown, for people to congregate. Its ¾-million-dollar budget got raised locally. I spent over a year there, conversing with people, listening to stories, exchanging ideas, and making it real. When completed, it functioned and provided space for a 9/11 ceremony, months of weekly anti-war vigils, the first Cinco de Mayo celebrations, First Nights, and beer fests.

Along the way, there was much pleasure, and there were also complexities.

On the plaza, we decided early on, to place bronze-cast tools on pedestals in tributes to work in the Yakima Valley. The selected 7 objects included a saddle, a short-handle hoe, an Indian basket, a Singer sewing machine, and, as the area centers on apple growing, there is a harvesting bag, worked mostly by migrant workers.

selected 7 objects included a saddle, a short-handle hoe, an Indian basket, a Singer sewing machine, and, as the area centers on apple growing, there is a harvesting bag, worked mostly by migrant workers.

These bronze castings were to be sponsored by the city’s denizens, and the owner of a large orchard was committed to supporting the harvest bag. A plaque was to be placed next to each bronze to describe its labor. For apple picking, it included: “When the bag is full, the picker… slides the fruits through the open bottom into a collection bin. Each bin holds 840 pounds, or about 25 bagfuls. A good worker can fill a bin in less than an hour.” When it was shown to the sponsor, even though the facts were correct, he threatened to withhold financing. For that one, the plaque never got mounted.

When I visited the spot sometime later, a migrant family was there. They were laughing with each other and stroked the bronze bag with some familiarity. For that family at least, the wordings might have been superfluous.

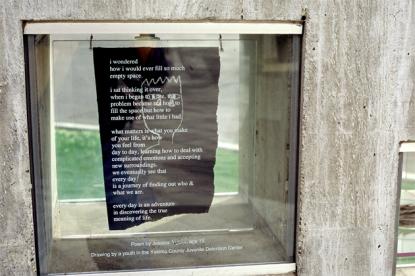

Another component of the plaza was to have 2 concrete walls with 39 windows which hold artifacts that express the community. Looking for those objects, I went to a juvenile detention center to do a workshop. A girl, 15-year-old, shuffled in late, head bowed, as per prison rules, hands behind back as though bound by cuffs. As the workshop progressed, others spoke up, she maintained a blank look. When addressed directly, she said that she had a poem in her “pod”; but was not allowed to go get it. The warden said, no problem, she would get it to me.

Months passed. Deadlines approached. I called the prison to enquire. The girl was long-released, and may not be approached directly. I left a telephone number; she called 10 minutes later. No longer having the poem, she said that she was not averse to writing another. That evening I went to her house. A blank man budged from the TV to open the door. The girl handed me the passage on a blue-lined sheet. It ended with: “Every day is an adventure / in discovering the true / meaning of life.” Later, the poem was inscribed on glass on a window on the plaza. I hope she got to see it.

Months passed. Deadlines approached. I called the prison to enquire. The girl was long-released, and may not be approached directly. I left a telephone number; she called 10 minutes later. No longer having the poem, she said that she was not averse to writing another. That evening I went to her house. A blank man budged from the TV to open the door. The girl handed me the passage on a blue-lined sheet. It ended with: “Every day is an adventure / in discovering the true / meaning of life.” Later, the poem was inscribed on glass on a window on the plaza. I hope she got to see it.

Such moments can be joyful, although “joyful” is not a satisfactory word. This is when I find being a cultural vagrant has certain benefits.

I left China before I came of age, so I never picked up the adult words for sex. When advanced enough to be curious, the available English words felt like barbs of marauders from across angry seas – faulty for more tender moments. As I gained in practice, the French word, la jouissance, for orgasm, entered my head, and it took. Later I discovered that Lacan worries about it, Roland Barthes looks for distinctions with it, and Duras writes to attain it. So, I say, why not, we can also take jouissance for those small wonders of bliss (no need for Hitchcockian fireworks or hand clapping down the runway) when things come together in art: when the viewer possesses the artist through the artwork, and the artist is transmigrated beyond the self.

Curiously, la jouissance is also a judicial term in French, meaning: to have the rights to enjoy one’s property.

So, a fantasy dances in my head: Walking home, after a good day’s work making art, humming a tune to the moon, to a rose-garden cottage with a sign by the gate, that says: “Ma jouissance”

IMAGES:

(1) Hotei Reaching for the Moon, after Sesson Shukei (Japanese, 1504-158)

(2) Wen-ti Tsen, Millennium Plaza, Yakima WA – general view

(3) Wen-ti Tsen, Millennium Plaza Yakima WA, poem by teenage girl

inscribed on one of the community object windows