In 2006, after Amherst College's Natural History Museum had been housed for nearly 70 years in the stately Pratt Gymnasium, the College invested $10 million to build it a new home. It is the fifth location for the college's ever-expanding scientific collections. With several stories of plate-glass windows, the new exhibition spaces are flooded with natural light and the room to explore and linger over discoveries. Since opening, the new facility has gone from welcoming 3,000 guests a year to hosting over 20,000.

The building itself is a handsome brick and glass edifice, but with a campus of fine architecture to compete with, it's been designed to emphasize what's inside: standing guard at the doors are two giant mastodon skeletons surrounded by other prehistoric creatures.

After 180 years of professors and alumni collecting in the field, as well as donations and purchases, the museum's inventories of carefully preserved animals, minerals and vegetables are rich and vast. Along with the grand displays of its most magnificent collections, hundreds of cupboards and drawers containing a multitude of smaller, more delicate treasures line the walls. Visitors are welcome to open them and study.

While the majority of what is on display are objects that provide scholars tangible examples from the physical universe that is and was—such as meteorites, fossilized branches and bones, and much fine taxidermy—the museum's most important collection, and largest of its kind, is not made up of nouns, but rather verbs. Not objects, but moments in time. Examining the objects contained within the Hitchcock Ichnology Cabinet—ancient markings left in hardened mud—is a lot like trying to interpret text on a page torn from an ancient book. Without knowing the authors or their intentions, students are left with only a brief temporal record of the scribe to interpret. Just scratches on a page, hieroglyphics on a tablet.

These days, even most four-year-olds would recognize the markings instantly as "dinosaur footprints," and their proud parents would commend them.

"Actually, not quite," Professor Edward Hitchcock might say if he were on hand to hear such an exchange (unlikely, as he's been buried for nearly 150 years). "Footprints, yes. Dinosaur: no."

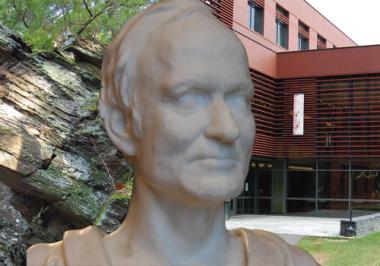

Hitchcock began amassing many of the giant slabs of rocks with strange, fossilized imprints on them in 1835, seven years before the d-word had been invented. He, for one, never accepted it. Though he was a man of strong convictions, who was respected around the world for his brilliant scientific mind and had the leadership abilities required to save the college from bankruptcy during his term as its president, Hitchcock was foremost an educator. His students and neighbors in Amherst, including a young Emily Dickinson, admired and loved him. He would have likely explained his reasoning to the child he'd corrected.

"That term, introduced by my esteemed colleague, Sir Richard Owen in England, is derived from the Greek, and it means 'terrible lizard,'" he might say. "While I will differ to Sir Richard's judgment as to the beast's temperament, my analysis strongly suggests the species was avian, not reptilian."

The father of American geological studies spent his life building a collection that he believed proved giant turkeys once stalked the Connecticut River Valley, long before pioneers ever arrived.

Prior to Hitchcock, there had been tracks found elsewhere in the region, and even a few bones had cropped up during excavation projects. While they were recognized as oddities and prized sometimes by those who found them, the Amherst College professor was the first to collect, study, and attempt to classify the tracks.

British scientists wrote the first chapter in the history of dinosaur discovery a few years before Hitchcock. Comparing fossilized bone fragments found in English ground with specimens collected from across the global empire of the United Kingdom, they extrapolated that their island once was tropical and occupied by long-extinct lizard-like creatures. The size of the specimens suggested to their discoverers that they came from fat, lumbering creatures that walked on all fours and dragged their tails.

Hitchcock wrote the second chapter, making similar leaps of imagination with his much more circumstantial evidence. When he started, he had nothing other than turkeys with which to compare the three-toed prints in the stone. He was aware of his colleagues' work and hypotheses, and he corresponded with them and others about his investigations, but when he died, he and they could not align their visions. If the Brits' creatures were sluggish belly-crawling beasts, his sometimes sprinted with great, leaping strides or meandered, but almost always on two feet. Some traveled in single file, others swarmed in flocks. If they had tails—only a few fossils have traces of a dragging appendage—Hitchcock's creatures kept them in the air.

Soon after Hitchcock died, more than just bone fragments were discovered by the first breed of scientists to consider themselves devoted to the new field. First in Belgium and then in the American West, full skeletons were unearthed of creatures far more exotic, dramatic and lethal than anything walking the Earth today. It required much more imagination to conjure a prehistoric beast by identifying a series of faint 18-inch-long dull impressions in a slab of rock than it did when you were standing beneath the assembled chassis of a loping 18-wheeler-long brontosaurus (75 feet) or the lurking menace of a 13-foot tall, 43-foot long tyrannosaurus with Nosferatu eyebrows.

As the dust settled from the excavation of trainloads of skeletons and fragments from across the globe to better endowed museums, the layers of fine rock dust buried both Edward Hitchcock's vision and nearly his ichnology cabinet, too. Along with his resistance to the d-word, he also wasn't enamored of the notion of an ice age, and he still hadn't warmed up to Darwin's radical thinking. Though still regularly mentioned in modern history texts, his copious writings, some of which came out in many editions during his lifetime, are now mostly over a century out of print, and until recently there has been no substantive biography.

The crowning success of the new Amherst College Natural History Museum is its resurrection of Hitchcock's amazing collection from the dark, dusty basement of the Victorian Pratt building. In their new home, the stone pages reside in a permanent gallery where they are displayed in a way that allows for the best interpretation. Rather than a cemetery, the room feels like a scrapbook of captured moments.

*

In October, 2009, paleontologists in China announced the discovery of a new kind of pterosaur, or fossilized flying reptile. Thus far pterosaurs have fallen into two distinct categories: the earliest had small heads and long tails, and their much larger descendants had short tails and much larger bodies and heads (these are more commonly known as pterodactyls). Until now, the fossil record showed no intermediary step between the two. In honor of the bicentenary of Darwin's birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his On the Origin of Species, this new pterosaur was dubbed Darwinopterus. As reported in Science News, researchers had anticipated finding pterosaurs with medium-length tails, heads and bodies to fill in the gap, but instead Darwinopterus had both a long tail and a large neck and head on a smaller body.

Dave Unwin of the University of Leicester in England, who coauthored the paper, said, "It's as if someone said, 'Let's nail these two together and make a sort of chimera, that'll really confuse everybody.'"

Metaphorically speaking, Edward Hitchcock could be seen as a similar kind of chimera philosophically linking together two world views that are seen today as wholly incompatible by those who espouse them: Christian creationists and scientists who adhere to Darwin's theories of evolution fueled by natural selection. The Amherst scholar was a devout Congregationalist who only ever intended his work and his collection to reflect God's majesty. Yet his discoveries and eon-spanning insights laid the groundwork for generations ahead to reconsider, and in some cases dismiss, the word of the Bible as authoritative.

*

Amherst College was established in 1821, primarily for training Congregationalist ministers to spread the Gospel across the world.

After two years as president of Deerfield Academy, the hometown school he also attended as a student, Edward Hitchcock abandoned aspirations of being an astronomer, and after studying at Yale for some months, he became a Congregationalist minister in the same year the college was founded.

He spent several uninspired years preaching to a parish in Conway until in 1825 he joined the college staff as professor of chemistry and natural history, a post he held for 20 years. He spent the next 19 years teaching under the title of professor of natural theology and geology. Before discovering the fossilized footprints that would lead him to establish the science of ichnology, Hitchcock was a geologist, another term that came into being after he'd been practicing it a great while. He was also the author of one of the first American textbooks on geology.

In 1832, Hitchcock published the first geologic map of Massachusetts and Rhode Island, traveling over 5,000 miles back and forth through the regions and climbing every mountain to record where mineral deposits lay. In part, his work, sponsored by the state, was an attempt to take an inventory of available resources, but the study of minerals, rock formations and geography meant much more to Hitchcock.

In his book Reminiscences of Amherst College, he wrote, "But I have found in geology a still higher source of gratification and one not expected. It has deepened my convictions of the truth not only of natural but of revealed religion… It has illustrated and confirmed many truths denominated evangelical. What are called the Doctrines of Reformation, which I adopted on the testimony of the Scriptures, I could not now give up without discarding geology also."

It was as a geologist that he was first consulted over a series of tracks discovered in Greenfield. Walking home from church on Sunday in March, 1835, W.W. Draper spotted strange impressions in the flagstones of a new sidewalk. His friend, Dr. James Deane, wrote Hitchcock, calling them "the tracks of a turkey in relief."

Initially, Hitchcock wasn't interested, but after Dr. Deane sent him plaster casts, the Amherst professor got on his horse, and a lifetime fixation began.

He had the sidewalk tiles loaded into his wagon so that he could study them at his leisure. That summer, he began scouring the region for more. He found other examples in Northampton's sidewalks, and this led him to the quarries where the stones had been harvested. The quarrymen in Gill were familiar with the tracks, which they also called "turkey tracks." They agreed to let him know if they came across any more.

Others pointed him to South Hadley where in 1802, a slab had been unearthed by Pliny Moody which contained a set of four three-toed tracks walking across the stone face. They were the first documented footprints found in America, but for 30 years the specimen had been treated as a curiosity and used as a fieldstone. As the markings were clearly ancient, locals suspected they derived from the time of the last great geological event they were familiar with—the Flood—and they were dubbed footprints from "Noah's Raven." Hitchcock convinced the owner that it deserved a place in his ichnology cabinet so it could be studied and preserved for future generations, and there it still resides, along with the sidewalk tiles themselves.

Stocking his cabinet became one of Hitchcock's life's chief goals and achievements, as he described in his Reminiscences:

"…As soon as I had turned my attention to Ichnology I commenced the accumulation of specimens, and from that day to the present I have never ceased to gather in all which I could honestly obtain. For no other part of the cabinet have I labored so hard or encountered so many difficulties. True, for some years at first I had the field essentially to myself, and had I then been fully aware of its richness and extent, I might have secured a large amount of specimens at a reasonable rate. But the subject opened upon me gradually, and the disclosures made by my writings attracted others into the field who became uncompromising competitors in the way or collecting, and with some it became a matter of trade. The consequence was that the value of specimens rose to almost fabulous prices."

Hitchcock made many of his own discoveries, climbing over exposed rock formations in Gill and Turners Falls with a hammer and chisel, and he became adept and finding and following layers of rock that were most likely to contain fossil traces.

Hitchcock reasoned that the rocks where the tracks were found were once comprised the muddy banks of a great lake or basin that filled what has since become the Connecticut River Valley. Creatures walking across the mud, plants falling into it, or water running across the embankments left impressions in the soft surface, and under the sun it hardened, preserving the marks. Layers of sediment covered the hardened mud, creating a new layer, and new impressions were made on top of that layer. Over millions of years, the layers became rock, and in cliff faces and in broken boulders, like the rings of a tree, the prehistoric mud seasons can be seen as strata. Splitting open these sheets of rock reveal what was written inside. The tracks left by the heaviest creatures sometimes made impressions several layers deep.

"…As I pried open, one after another, the folded leaves of this ancient record," Hitchcock wrote, "it revealed a marvelous history of the ancient Fauna of this Valley. It was a new branch of Paleontology, whose title-page had scarcely been written in Europe, but I had stumbled upon materials enough almost to fill the volume. Up to this hour I have been trying to spell out the hieroglyphics; and even now, I presume the work is only begun."

Some of the challenges Hitchcock faced collecting in the field were from competitors. "Suppose on your arrival at a locality of footmarks," he wrote, "one had preceded you with whom you were on friendly terms, but who was so anxious to prevent your obtaining any specimens that he had mutilated the good ones that were accessible, which he had not time to remove! Alas, if I had not known this vandalism practiced several times by professedly respectable naturalists, I should not mention it." On one occasion, while in New York City, he found an impression in a sidewalk tile on Greenwich Street, and he "requested a moulder to take a plaster cast of them, which he did." Returning a day later, he heard that someone else had also taken a cast of the impressions, "although he could not have known they were of any value… it shows how prone men are to follow an example."

When he returned to Amherst, hauling his new finds in his own business wagon, he typically arrived in the evening, "because, especially of late, such manual labor is regarded by many as not comporting with the dignity of a professor."

To spare his dignity he often purchased items for his collection, both from local auctions and overseas, and many of his Reminiscences are detailed accounts of how he managed to raise funds and negotiate auctions so that he could win the best samples for his college's collection. When he visited Europe late in life, he returned with many fine samples which still are in the collection.

*

Over time, Hitchcock began to realize that the creatures that left the impressions were probably something different than overgrown turkeys. One creature left a footprint so deep he could fill the impression with a gallon of water. Some skitted lightly across the mud on all fours with a long, thin tail dragging behind. A cast he brought back from Germany seemed to have the toes of a frog. He came to identify more than 90 different species in the rocks he collected—recent efforts have narrowed the number down to under a dozen—and while he accepted his British colleagues' analysis that their fossils represented lizard-like creatures, the American creatures he looked at were always birds to him.

Until he left the country late in life, Hitchcock lived his entire life in the Connecticut River Valley, and he never saw a lizard. To a certain degree, he resisted the dinosaur idea out of a sense of distaste: the descriptions he read of the giant iguana-like animals that excited Owen's imagination sounded repulsive to him, and not worthy of his creatures. But this wasn't just obstinacy and prejudice. Along with the tracks, Hitchcock found coprolites, dinosaur droppings. He sent a chemist colleague the samples he dug up from the Chicopee Falls, and the scientist was able to isolate enough uric acid in the find—which is what birds excrete, as opposed to urea in mammals—to support Hitchcock's hypothesis. Also, in 1839, explorers in New Zealand discovered the remains of a recently extinct bird, the moa, whose clawed foot offered a near match to some of the tracks in Hitchcock's cabinet, and he felt it offered proof such creatures could have also lived in prehistoric New England.

*

To celebrate the 150th anniversary of Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species, which occurred on November 24, an evangelical group published 100,000 free copies of the book to be distributed on college campuses. While Darwin's text is presented without edit, Ray Comfort, the group's leader, provided a 50-page introduction that challenges the famous biologist's conclusions about evolution fueled by natural selection, arguing that the two beliefs deserved to be considered in tandem. CNN reported that atheist biologist Richard Dawkins had sneered at the effort, saying, "There is no refutation of Darwinian evolution in existence. If a refutation ever were to come about, it would come from a scientist, and not an idiot…. Hunches aren't interesting, hunches aren't valuable. What's important is scientific evidence."

In Nancy Pick's rich biography of Hitchcock, Curious Footprints, the local author points out that prior to the publication of Darwin's book in 1859, the idea of evolution had been floated by other scientists. Darwin's advance was explaining the mechanism, natural selection, that made evolution work. Hitchcock believed in none of it, and debated points in letters with Darwin and others. Pick writes, "Hitchcock embraced the notion that has so oddly made a comeback in recent years: intelligent design. Under this rubric, nothing was random. There was no place for a cruel, mechanistic device like survival of the fittest. Hitchcock believed that God had created (and destroyed) successive generations of animals, in separate acts of creation. Each species was designed to perfectly fit the niche in which it lived."

The Amherst theologian and scientist lived a long and distinguished life, allowing both disciplines to influence his work and vision of the world's vast geological history. Reconciling his faith with his scientific observation of the world was not a matter of conflict, but philosophy and linguistics. Working with the original Hebrew, Hitchcock offered a wily new interpretation of the first line of Genesis, allowing for creation to take thousands of years rather than a few days.

In his diary, he asked that after his death, should the college "fall into the hands" of those who did not share his faith (he had a list of acceptable branches of Christianity), ownership of his track collection would revert to his family. He wrote of such an infidel leader, "…if he adopt another Gospel I do not wish to aid him in promoting it."

Hitchcock was living proof that scientific fact and religious faith could be contained comfortably in one brilliant mind, and despite Dawkins' protestations, Hitchcock's hunches were both interesting and invaluable.

After Darwin published The Voyage of the Beagle in 1839, Hitchcock sent him a copy of his Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts. With it, he included news of his tracks. In a letter, Darwin thanked his colleague in Amherst for the book. Of the fossil discoveries, he wrote respectfully that while they were sure to be "one of the most curious of the present century," he did not share Hitchcock's suspicions that they were made by avian-like creatures. "[T]heir structure branches off toward the Amphibia," he hypothesized.

Though no one has proved conclusively whether the creatures that made tracks in the Pioneer Valley had feathers or not, 150 years later, paleontologists are beginning to attribute avian characteristics to the species they study. In museums across the world, dinosaur models are starting to sprout feathers. Raptors, the creatures represented as giant, cunning lizards hunting children through an industrial kitchen in Spielberg's Jurassic Park, are now seen as having a fringe of feathers hanging from their upper arms and possibly plumage on their heads. Track discoveries in the decades since Hitchcock's point to flocking behaviors.

Because Hitchcock sided with a pedagogy that fell out of favor, even work that would later be embraced was largely forgotten for generations. As vehemently as he hoped his work would not fall into the hands of people he considered heretics (such as atheists), today some of the scientists who rule the roost sneer at faith and reject the validity of beliefs they don't share.

Yet both sides will continue to share a life-consuming passion for describing entities they will never see and imagining worlds they will never visit.

The Amherst College Natural History Museum is free and open to the public Tuesday through Sunday, 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. Thursday nights it's open from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m.

Curious Footprints by Nancy Pick, the most in-depth biography of Hitchcock, is available at the front desk of the museum for $20.