In a lengthy and widely cited cover story for theJanuary/February 2010 issue of The Atlantic magazine that serves as the conceptual framework for Mass Humanities’ seventh annual fall symposium and is paradoxically entitled “How America Can Rise Again” (I say paradoxically because his conclusion is that we probably cannot rise again – but that’s okay because we really haven’t fallen behind in any important respects), national correspondent James Fallows makes a number of interesting and provocative arguments.

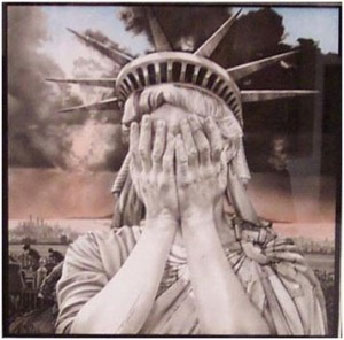

Lamentations over a Fallen Republic are a venerable (and useful) political tradition in American history, predating even the establishment of the republic itself. Entire books have been written on the subject (several of which are cited in Fallows’ essay). Predictions of national decline are nothing new. But for all that, they may still be true.

There are two different ways in which the rise or fall of America can be measured: externally–whether we are performing better or worse relative to other nations, or internally–whether we are living up to our own ideals. The fact that the American economy, the largest and most robust in the world since the end of World War II, will sooner or later be overtaken by China, and perhaps by India and even Brazil, is inevitable and not particularly worrisome. We should be much more concerned about the structural soundness of our economy, and about what we are producing, than about the relative size of our economy.

Fallows does not address this issue, except with a passing glance, but American military hegemony must come to an end also, both because we can no longer afford such a vast and wasteful presence of U.S forces across the globe (according to one prominent expert, the U.S. has some 700 military bases in foreign countries and military forces operating in about 150 of the world’s 193 countries) and because we are passing from a unipolar to a multipolar world order. Increasingly, other nations do not want their destinies to be controlled by the United States. This is probably a blessing in disguise. Repatriating tens of thousands of troops ill-trained for civilian jobs will, however, place an additional stress on an economy still lingering through a jobless recovery. This is a burden, not a blessing.

America’s unchallenged strengths, according to Fallows, are (a) the best universities in the world that attract talented people from all over the globe (except, of course, talented people from the Muslim world who cannot get visas); (b) an openness to immigration (except, of course, from the Muslim world and for poor people from Latin America); and (c) a culture that places a high value on innovation, reinvention and “crowdsourcing.” These make American society remarkably resilient.

Fallows recognizes that America is falling short in all sorts of ways domestically (e.g., the failure to invest in infrastructure maintenance and improvement, the loss of middle class jobs, etc.) and while he overvalues our progress in some important areas (e.g., race relations – so what if the life prospects for young black males in this country are as bleak as they were under Jim Crow, hey, we have a black president! – and human rights more generally), and ignores serious problems in other areas (e.g., the rapid and unconscionable accumulation of wealth at the very top of the income scale, the rising cost of higher education), he nevertheless hits the nail right on the head in diagnosing our most serious problem. Solutions to virtually all of our problems abound, but we have an antiquated and dysfunction political system that is incapable of acting in the best long term interests of the people and is utterly resistant to reform. Our society is fine. Our polity is broken.

Fallows recognizes that America is falling short in all sorts of ways domestically (e.g., the failure to invest in infrastructure maintenance and improvement, the loss of middle class jobs, etc.) and while he overvalues our progress in some important areas (e.g., race relations – so what if the life prospects for young black males in this country are as bleak as they were under Jim Crow, hey, we have a black president! – and human rights more generally), and ignores serious problems in other areas (e.g., the rapid and unconscionable accumulation of wealth at the very top of the income scale, the rising cost of higher education), he nevertheless hits the nail right on the head in diagnosing our most serious problem. Solutions to virtually all of our problems abound, but we have an antiquated and dysfunction political system that is incapable of acting in the best long term interests of the people and is utterly resistant to reform. Our society is fine. Our polity is broken.

Fallows singles out the United States Senate for special abuse – and the Senate is a deserving target. (See, for example, George Packer’s darkly hilarious exposé in the August 9 issue of The New Yorker.) But the presidency (see Todd Purdum’s, “Washington, We Have a Problem,” in the September issue of Vanity Fair), the Supreme Court (see Adam Liptak’s New York Times article on the polarization of the Robert’s Court – which, in a stunning, shamelessly partisan, and ultimately tragic overreach of its authority anointed George W. Bush President of the United States ), and the House of Representatives (where Minnesota Republican and certified nutcase Michele Bachmann spent almost $9 million to win a House seat–chump change compared to the $42 million Connecticut Republican Linda MacMahon spent losing a Senate seat) are also dysfunctional if less undemocratic. The total amount spent in last month’s Congressional elections was a staggering $850 million. What good did all this money produce?

But our problem goes deeper than antiquated political institutions, the corrupting influence of money in politics, and politicians who care more about maintaining power than they do about solving the nation’s problems. The really fundamental problem in America is the lack of a shared social vision without which political solutions to these problems are simply unattainable. With a shared social vision come mutual trust and respect. These too are absolutely necessary and sorely lacking in our politics today.

This is why the humanities are so relevant to the current conditions of our national life. For where do we find the values and beliefs, the ideals and aspirations out of which a shared social vision may be constituted except in the humanities? History, literature, philosophy, the arts–these are the great fonts of wisdom and self-knowledge in any civilization. The founders of our republic were deeply grounded in the tradition of thought and learning we call the humanities. Indeed, they are now themselves an important part of that tradition.

This is why the accelerating trend in our colleges and universities toward devaluing the humanities is so shortsighted and even dangerous to our democracy. The recent brouhaha over the University of Albany’s decision to eliminate five humanities programs is only the most public and egregious example of this devaluation. It has been going on quietly and incrementally at most universities for decades.

Sadly, our society does not value the humanities per se, but I believe it does value the skills, capacities and habits of mind that derive from the study of the humanities: the power of imagination; the ability to distinguish fact from opinion, and to marshal and assess evidence; the respect for truth; empathy, cultural sensitivity, intellectual humility, critical reading, critical thinking, clear and persuasive writing, and the ability to think “outside the box.”

These capacities are crucially important to almost every aspect of our society–from business to the professions and politics. In a nation like ours that is self-governed, developing these capacities should be seen as a responsibility of citizenship, and a university, a government or a free people that devalues the humanities is indeed in decline.