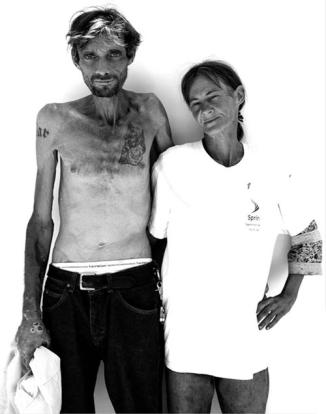

Photo by Lynn Blodgett, from his book, Amazing Grace: The Face of America’s Homeless (Earth Aware Editions, 2007)

In 1999, Give US Your Poor received a pre-production grant from Mass Humanities towards a feature length documentary on homelessness. That grant allowed us to convene experts addressing homelessness, service providers, homeless people, and government officials to map out essential themes in addressing homelessness in the U.S. and to engage humanities scholars. Our vision of a full length documentary never came to fruition despite having great storylines, great humanities scholars involved, Academy Award-winning filmmakers, and celebrity supporters. The big funding remained elusive despite our coming very close to securing it a couple of times.

As we searched for film funding, along the way we developed a humanities-based classroom curriculum, and later a multi-media writing curriculum, each of which proved to have a life of its own. We convened numerous community forums that brought together diverse stakeholders to look at creative ways to collaborate in addressing homelessness; engaged a large number of partner organizations and individuals nationally; developed college scholarships locally and nationally with partners for homeless students; promoted a holistic, systems thinking approach to ending homelessness with policy makers; and we developed a college course on the history of homelessness. In 2007, we released with Appleseed Recordings a music CD featuring homeless musicians and celebrity musicians (including Bruce Springsteen and many other great artists), and held related concerts with artists from the CD. In 2009-2010, we came full circle, releasing a documentary film short that played in 37 film festivals across the U.S. Slowly we had evolved from just a film project, to what we are now, a national campaign housed at the University of Massachusetts Boston’s McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies.

Through this evolution we have remained true as an organization to the mission that started with the film. It is two-fold: (1) to dispel myths about homelessness and (2) promote structural solutions.

Since this is a humanities forum, a word about homelessness and history: We’ve learned a lot about addressing the issue of homelessness with different audiences in the past 10 years. For one thing, the subject (whether for donors or audiences) can be touchy. It’s not always a happy subject (over a million homeless children; ever-increasing homeless veterans, overall numbers rising dramatically with increased foreclosures and unemployment, etc.). Also with increased unemployment, foreclosures, high healthcare costs, and two prolonged wars, many people are peering at the edge of homelessness who were not before. This has always been the case in poor economic times in the U.S., but more significantly when there has been economic transition.

Many people have told me that there was not really a history of homelessness, that this is a modern phenomenon. But that is simply not true. Historian Ken Kusmer, author of Down And Out reminds us that we have had periods of homelessness in the past besides the well-known homelessness conditions of the Great Depression. In the 1980’s (the start of modern homelessness) we saw the shift from a manufacturing economy to a service/information economy. Kusmer describes a similar shift in the late 1880s when the nation moved from an agricultural economy to a manufacturing one. Both shifts meant upheaval for many workers that were left extremely vulnerable and, in the worst cases, without a home. That left many people more vulnerable, and when combined with illness, injury, strained social networks, the combination became a type of homelessness cocktail.

The stigma of having no home in that era, true today as well, is evident in Stephen Crane’s, “An Experiment in Misery,” which first appeared as an article in the New York Press (1894) and was later released as a book (1896).

He was going forth to eat as the wanderer may eat, and sleep as the homeless sleep. By the time he had reached City Hall Park he was so completely plastered with yells of “bum” and “hobo,” and with various unholy epithets that small boys had applied to him at intervals, that he was in a state of the most profound dejection.

War veterans have also been overrepresented among homeless people in American history. In the modern era, Vietnam veterans and veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars may return with psychological and physical scars that extend the war beyond the battlefield, can lead to drug addiction and/or isolation from others, and for many, homelessness. A number of Civil War veterans were also homeless. Many became accustomed to traveling, living on the road as soldiers, and once the war ended in 1865 continued doing that either for economic reasons, afflicted by the war, or because they had nothing to go back to.

Why is a historical lens on homelessness important? There is a belief that homelessness is tied to modern times and economic recession. When the economy declines, some people are left homeless. It seems logical enough. But history shows us that this is not the case. Other forces are at play. In the early 1980s when Ronald Regan took office, the economy was horrible and homelessness was becoming visible in ways that were new, including an upsurge of homeless families. When the economy recovered and soared for many in that decade, rates of homelessness continued to rise. It rose through the Bill Clinton 1990s, during the dot.com explosion, and it rose through the economic downturns of 9/11 and the Great Recession of 2008-2009 during George W. Bush’s presidency. Latest federal data indicates rates of homelessness are currently holding steady. We’ll see if that is accurate.

Today our challenge is not to get stuck with the same old models, not play the blame game across ideological sides, and not to assume a rising tide will lift all boats. Instead we need to take a holistic, systemic look at homelessness. We need to collaborate across federal departments more than ever, and across sectors. And through our work we need to always maintain a humanistic—especially historic—perspective.

When we think of ourselves as Americans at our best, we think of the inscription at the based of the Statue of Liberty, in Emma Lazarus’s 1883 poem, “The New Colossus” from which our organization derives its name. It’s a vision of America symbolically reaching out to those in need of comfort and offering welcome, and, implied, a home.

Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refused of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

If you are concerned about homelessness in Massachusetts or elsewhere in the U.S. and would like to join our campaign, please visit our website at www.giveusyourpoor.org to (1) sign up for our newsletter, (2) make a donation, (3) engage your company, (4) host a house party, or (4) volunteer in other ways. Thanks!

For further reading on homelessness and history, click here for a piece that Howard Zinn wrote for Give US Your Poor and the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities.