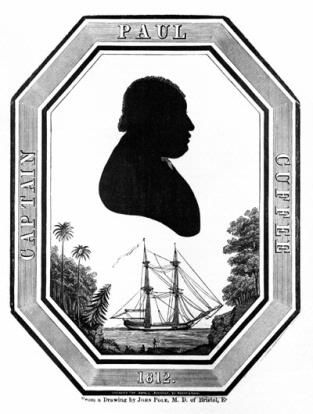

Although I grew up in and around New Bedford, Massachusetts, the first time I heard the name of whaling Captain Paul Cuffe was when I was a freshman in college. I was stunned to learn that there had been a 18th century whaling captain and sea merchant of African and Native-American descent who had walked the same streets as I had and I had never seen a single reference to him or his history.

Although I grew up in and around New Bedford, Massachusetts, the first time I heard the name of whaling Captain Paul Cuffe was when I was a freshman in college. I was stunned to learn that there had been a 18th century whaling captain and sea merchant of African and Native-American descent who had walked the same streets as I had and I had never seen a single reference to him or his history.

New Bedford is rightfully proud of its preeminence as the whaling capital of the world and the richest city per capita in 1850. The beautiful mansions and public buildings attest to that legacy. The streets, schools and parks are named after the Quaker families who built and profited from the whaling history and the textiles that followed.

Every New Bedford child at the time of my own childhood was very familiar with Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and had probably read at least three versions of it before graduation from high school . . . the comic book, the Cliff Notes and one abridged version in senior year. We had read about Ishmael, Starbuck, Ahab, but also Tashtego, Queequeg and Dagoo. As elementary school children we had each made the class trip to the New Bedford Whaling Museum to learn about the city’s past. We learned about scrimshaw and saw oil paintings of stern old whaling captains and their wives. Paul Cuffe was not in their company. In fact there was not a single black or brown face to be seen.

There was, however, one exhibit that resonated with all of us. It was a tiny re-creation of a 17th century Old Dartmouth kitchen with a table and a cradle in front of a brick fireplace. The walls were ancient pine boards from a farm house in Westport, Mass. It was a quiet contemplative place that became our favorite place in the Museum, more so than the half scale whaling ship, the harpoons or the scrimshaw.

Decades later. I’d been away from Massachusetts for college, law school, a career in show business in Los Angeles and New York, and fate drew me back to New Bedford. Times had changed, as has the city. Over those many years I had learned not only of the major contributions of Native Americans, African-Americans and Cape Verdeans to the Yankee whaling industry, I had also discovered something that had been lost in my own family: the knowledge that both my grandfather and great grandfather had been whalers. It was whaling that had given each of them the opportunity to ride the wings of fortune from desolate Cape Verde to Nubetfet.

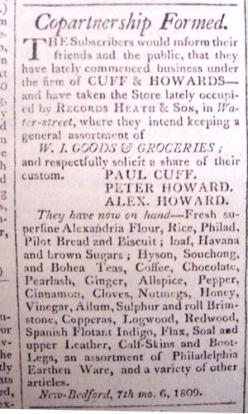

More discoveries have followed since I joined the staff of the Whaling Museum. After revisiting the old kitchen gallery, I was stunned to hear from a former trustee that the pine wall boards in that room had been taken from not just any farm house in Westport, MA, but from one of the homes of Captain Paul Cuffe. At a Cuffe Symposium a year earlier I had learned that Cuffe had also owned a West Indian Import store on Water Street which abuts the Museum. Research since then has indicated that a portion of the Museum is actually built on the site of Cuffe’s store.

All of this culminated in a visit to the Museum by the second graders from the Paul Cuffee (sic) Charter School in Providence, Rhode Island. Those second graders, all so knowledgeable about the life of Capt. Cuffe, shamed me. At their young age, they knew more about Cuffe than I did. When they visited the kitchen it was like visiting a shrine. When they stood on the site of the store, they eagerly asked if Mr. Cuffe was inside to sell them something from the West Indies. They asked me what made Mr. Cuffe so sad that he turned briefly to alcohol? Why didn’t the government let him vote if he was a rich man? Was Capt. Cuffe an Indian or an African-American? There were far more questions than answers.

Their knowledge of local history was more complete than mine. A gallery that was just a period kitchen to me when I was a child, to them was a room that inspired them and testified to the truth that it was possible to be the son of a formerly enslaved African man and a Wampanoag woman and still rise to be a successful merchant and a whaling captain. The pine boards told them that they were in the presence of the greatness of Paul Cuffe, an American original.

In my mind, all this begged the questions of who owns history? Who shapes history? Why are some people left behind and forgotten while others are celebrated as heroes? How could I grow up surrounded by so much history and know so little? For those of us who attempt to preserve and interpret history, what is our collective responsibility? On what basis do we omit or include?

It all came back to a simple kitchen gallery exhibit that means so much more today than it did 40 years ago. Now through the generosity and guidance of Mass Humanities and the inspiration of the Charter School second graders, it has evolved into the Cuffe Kitchen Gallery. There are very few artifacts in the exhibit but few are needed to evoke the legacy of Captain Paul Cuffe and the world he lived in. There are his pipe and his compass. Imagine the years of contemplative thought that flowed through that pipe. Think about the places that compass took Cuffe and how it was his key to a world greater than his hometown, a world that inspired him to challenge the status quo and seek justice for all people, including voting rights for all Americans in 1800, regardless of color, an integrated school for children of all colors and classes.

Now through the generosity and guidance of Mass Humanities and the inspiration of the Charter School second graders, it has evolved into the Cuffe Kitchen Gallery. There are very few artifacts in the exhibit but few are needed to evoke the legacy of Captain Paul Cuffe and the world he lived in. There are his pipe and his compass. Imagine the years of contemplative thought that flowed through that pipe. Think about the places that compass took Cuffe and how it was his key to a world greater than his hometown, a world that inspired him to challenge the status quo and seek justice for all people, including voting rights for all Americans in 1800, regardless of color, an integrated school for children of all colors and classes.

If that Cuffe kitchen could speak we would hear the voice of a wealthy man of color who was denied his place in history because of his background. We would hear the voices of his Native American mother and wife and know of their day to day challenges.

The new Cuffe Kitchen is again one of my favorite places in the Museum. Still, it is a contemplative spot that inspires. These walls do talk.

CAPTAIN PAUL CUFFE TIMELINE

January 17, 1759 Paul Cuffe born on Cuttyhunk to Cuffe Slocum and Ruth Moses. He was born free.

1766 The Cuffe Slocum family moved to Dartmouth, Mass.

1772 Cuffe Slocum died.

1775 At age 16 he signed board his first whaling ship where he learned navigation. In his journal he called himself a “marineer”

1776 17 year old Paul Slocum was captured by the British and held for 3 months during the American Revolution

1778 “Paul Slocum” became “Paul Cuffe”

1779 Paul Cuffe and his brother David built a small boat to ply the nearby coast and islands.

January 6, 1787 Ruth Moses Slocum died

1780 At the age of twenty-one, Cuffe refused to pay taxes because free American blacks did not have the right to vote. In 1780, he petitioned the county government to end such taxation without representation. The petition was denied, but his suit was one of the influences that led the Massachusetts Legislature to grant voting rights to all free male citizens of the state, regardless of color in 1783.Cuffee finally made enough money to purchase another ship and hired crew. He gradually built up capital and expanded ownership to a fleet of ships. After using open boats, he commissioned the 14 or 15 ton closed-deck boat Box Iron, then an 18-20 ton schooner

February 25, 1783 Cuffe married Alice Pequit, Native American and settled in Westport, Mass where they raised their seven children: Naomi (born 1783), Mary (born 1785), Ruth (1788), Alice (1790), Paul Jr. (1792), Rhoda 1795), and William (1799)

Late 1780s Cuff’s flagship was the 25-ton schooner Sun Fish, then the 40-ton schooner Mary.

1795 The Mary and Sunfish were sold to finance the construction of the Ranger – a 69-ton schooner launched in 1796 from Cuffe’s own shipyard in Westport.

February 1799 Cuffe paid $3,500 for 140 acres of waterfront property in Westport.

1800 He invested in a half-interest in the 162-ton Bark Hero.

1801 Paul Cuffe was one of the most wealthy African American in the United States.

1806 His largest ship, the 268-ton Alpha was built, along with his favorite ship of all, the 109-ton Brig Traveller. With his sons in laws, the Howards, in New Bedford, he owned and operated a West Indian import/export business at the “Four Corners” of Water and Union Streets known as “Cuffe and Howards.” He established one of the first racially integrated schools in the United States in Westport.

March 1807 Cuffe joined the fledgling efforts to improve the colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

1809 Cuffe joined the Sierra Leone project

December 27, 1810 Cuffe left Philadelphia harbor and launched his first expedition to Sierra Leone. Cuffe reached Freetown, Sierra Leone March 1, 1811

April 1812 Paul Cuffe met President James Madison at the White House

1813 He donated most of the money to build a new Friends Meeting House in Westport.

December 10, 1815 Cuffe sailed from Westport with thirty-eight Black colonists (18 adults and 20 children ranging in age from 8 months to sixty years). The expedition cost Cuffe expenses of over $4000. Passengers paying their own fares plus a donation by William Rotch a friend of Cuffe.

September 9, 1817 He died in Westport, Mass.