In contrast to many other types of archaeology, the historical archaeologist often has at his or her disposal a rich collection of written records such as letters, plots, and account books to add to their interpretation of a site. In some situations, there is little written documentation of a site and the archaeological data must fill in the gaps to help answer the researcher’s questions. Other times, the opposite is true and one must rely more heavily upon the documentary record to understand what transpired at a site at a given point in time. In some lucky circumstances, the archaeology and written record come together and allow us to capture a glimpse of a brief moment in time. The assistance of these two forms of data can help us see, albeit briefly and with a little imagination, what life may have been like for people in the past. It is very easy to lose sight of the fact that a historical reference or a small pot shard in the ground represents people who were in many fundamental ways just like us: individuals who had real lives and emotions, fears, and senses of humor. Archaeology gives us a tangible link to the past and the following article will focus on two examples from eighteenth-century Massachusetts in which that connection is revealed.

In 2006 a small archaeological excavation took place at the site of a mid-eighteenth-century French & Indian War-era fortified farmstead in Charlemont, Massachusetts.

The initiative, known as Taylor’s Fort Archaeological Project, revealed artifacts and architecture from the history of Western Massachusetts spanning from as much as 3,000 years ago up to the present day.The  focus of the project was the Taylor family and their lives during the 1750s conflict

focus of the project was the Taylor family and their lives during the 1750s conflict between Great Britain and France that forced the early settlers of the surrounding townships to fortify their homes. Though the history of a given time and place is often concentrated on the broad political or social trends of the day, historical archaeology can offer us a glimpse into everyday life as it was lived.

between Great Britain and France that forced the early settlers of the surrounding townships to fortify their homes. Though the history of a given time and place is often concentrated on the broad political or social trends of the day, historical archaeology can offer us a glimpse into everyday life as it was lived.

One such moment was revealed through both the archaeological and documentary records. In August of 1756 came an account “from Cherlymont” with news that Othniel Taylor’s son had “fell out of ye mount and hurt himself” which resulted in Taylor traveling on horseback to Deerfield “to Git the Dockter to go to his Child”.[i] At the time, Deerfield was the closest source of many things, in this case most importantly a physician. In the 1750s, the resident was Thomas Williams, whose home still stands on the main street of Old Deerfield. While Taylor’s Fort had a palisade and housed a militia, it was first and foremost two households composed of families. From the account it is very tempting to imagine the young Taylor climbing among the wood staging of the watchtower like any child would. With the young militiamen about, taking turns at their post or playing games within the palisade walls, it is not a stretch to propose that the boy may have been attempting to impress the men with his daring. As is often the case in similar situations, an accident occurred. Though the record is silent, the boy’s father traveled to Deerfield and was accompanied home by Dr. Williams who saw to the child’s injury. This assumption can be made because archaeological evidence of the administration of medicine and ointments was recovered during the excavation, including small blown glass bottles that would have held various cures of the day.[ii] Though we cannot say that these bottles represent the remedy for this specific injury, they almost certainly indicate medicines prescribed by Williams during the period.

Another small moment in the lives of Taylor’s Fort occurred right around the same time in the summer of 1756. During that period, the fort and others like it in the neighboring townships were designed to protect small farmhouses and give advance warning of enemy troop movements in the region. The year before, two men had been killed and two others were taken captive just a few miles to the west in Charlemont. The subsequent heightened sense of alarm led to the following event. One morning, the residents of Taylor’s Fort heard a volley of musket shot from Rice’s Fort a few miles to the west. This was the way in which this chain of forts could give advance warning of an attack to the larger communities like Deerfield; upon hearing the alarm blasts, the next fort would shoot off their weapons and the alarm would be passed. The account shows that upon hearing this, Deerfield had mustered 50 men that had quickly “gonto ther sistenc” in Charlemont.[iii] This story, however, had a more humorous ending, for the same document revealed that “the a larom began at Hawkses [Fort] by 3 men shutting at Ducks”.[iv] Though the Deerfield men may have  been a bit annoyed by the false alarm, relief and perhaps a bit of hilarity at

been a bit annoyed by the false alarm, relief and perhaps a bit of hilarity at the circumstances may have been the dominant sentiments. Evidence of firearms and hunting activity was also revealed at the site of the fort. These weapons served crucial roles in the fortified farmstead. The inhabitants needed to bring in fresh venison and other meat, used their rifles to hunt various species for their pelts that would later be traded for cash or credit at Deerfield. Inhabitants were prepared to use their weapons to resist French soldiers or their Native American allies, and as we learn from above, to send an alarm (albeit false) to their far-flung neighbors.

the circumstances may have been the dominant sentiments. Evidence of firearms and hunting activity was also revealed at the site of the fort. These weapons served crucial roles in the fortified farmstead. The inhabitants needed to bring in fresh venison and other meat, used their rifles to hunt various species for their pelts that would later be traded for cash or credit at Deerfield. Inhabitants were prepared to use their weapons to resist French soldiers or their Native American allies, and as we learn from above, to send an alarm (albeit false) to their far-flung neighbors.

A great deal was learned about life in Taylor’s Fort during the 1750s and 60s through the documentary research and archaeological excavation. The project focused on many broader questions regarding the material culture of the site. However, it is the small things that are often most successful in transporting us back in time. It is these events and small material cues that help us imagine what little aspects of life may have been like for these people on the Massachusetts frontier.

Photos:

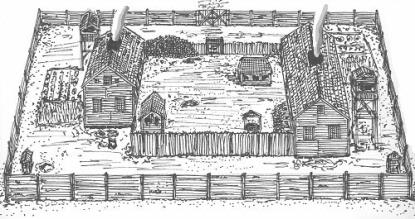

Image 1: Conjectural illustration of Taylor’s Fort as it may have appeared in the 1750s

Image 2: Late Archaic projectile point dating from approximately 3,000 years ago

Image 3: 1853 US half dime

Image 4-5: Pharmaceutical glass bottle fragments

Image 6: Flintlock musket flint during excavation

Image 7: Lead musket ball

[i]See, John Hawks (1756-1757) Diary of John Hawks. Photocopy at Memorial Library: Deerfield, MA. Reproduced from the collections of the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[ii] Identical bottles were found during archaeological excavations at the Williams’s House in Deerfield. See, Brooke S. Blades (1976) Cultural Behavior and Material Culture in Eighteenth-Century Deerfield, Massachusetts: Excavations at the Dr. Thomas Williams House. Submitted to Historic Deerfield Inc. Photocopy at Memorial Library: Deerfield, MA.

[iii] See, Hawks (1756-1757)

[iv] Hawks Fort was another Charlemont fortification. See, Hawks (1756-1757)