It’s a typical day in the affectionately named “Nerdodrome,” the Hampshire College headquarters of Bit Films, which describes itself as “in part, an attempt to bridge the gap between academia and industry” in the field of computer animation. Comprised of a central suite where staff, student interns and visiting artists labor for untold hours and a neighboring “render farm”—essentially a room full of processors from which you can almost smell a tangy, smoky effluence of silicon working overtime—the whole of the place is warm and low-key, not quite the sterile bat-cave one might expect to find at such a hub of pixel-powered geekdom.

The Bit Films program, essentially a student/intern-staffed digital animation studio, was founded in 2002 by Associate Professor of Media Arts Chris Perry, a San Francisco native and former technical director and programmer with Pixar Animation Studios and Rhythm & Hues Studios. With its intense internship program for aspiring animators and other digital artists and producers, Bit Films has seen alumni move on to professional positions at industry giants like Pixar, DreamWorks and Weta Digital, among others. In-house, Perry and his transient waves of would-be dream-weavers have produced independent shorts including Catch, Displacement, The Incident at Tower 37 and Caldera, all of which have been or will be screened at a whopping number of international film festivals, and in the process racked up an impressive number of awards (watch them at www.bitfilms.com). Caldera, the most recently released short principally created by Perry and former students Evan Viera and Chris Bishop, premiered this year at Austin’s SXSW Film Festival and has also won the Prix Ars Electronica Award of Distinction and Best Animated Film at the Rome International Film Festival (RIFF). It was also screened May 10 at Amherst Cinema to a sold-out crowd, and is headed for more festivals in the U.S. and Europe over the summer.

A couple of the aforementioned visiting artists, independent producers named Bassam Kurdali and Fateh Slavitskaya, founded a company called URCHN (urchn.org/), an animation production studio that has, between occasional paid commercial/industrial B2B (business-to-business) video assignments, been quietly but mightily helping to advance a global movement in “open film production.” Both UMass alumni, the two are currently helming a roughly 10-minute animated short called Tube, a project that, even at its modest length, is being created by 56 artists in 22 countries—including countries technically at war with each other. The labor, the division of which is greatly enabled by high-speed Internet connections, is delegated to dedicated team players from Berlin to Cape Town to Buenos Aires. They collaborate to provide conceptual art, modeling, design, rigging, rendering, lighting, compositing, animating, texturing and many other functions—much like a team working on a commercial film production.

The primary difference here is that, other than a small amount of seed funding from Kickstarter pledges (which, as of this writing, are up to a fairly robust $30,000), and what Slavitskaya calls a “massive in-kind donation” in the form of Hampshire’s allowing them to use its render farm in exchange for mentoring students, no one’s getting paid. Much of the project’s goal is purely academic—allowing aspiring animators to get in thousands of digital push-ups and absorb, replicate and perfect the hundreds of techniques available to them within the tool palette of a rigorous combination of art and technical prowess. As URCHN’s mission statement puts it, among its primary goals is to “explore the versatile medium of animation independent of typical commercial pressures that restrict it to genre.”

“One of our middle-term goals is to create more public subsidy, connecting non-profits to either students or other people who want to take on a new multimedia toolset based in free/libre and open source software,” she says. “In Europe there’s funding to support that training so that students don’t have to pay out of pocket if they want to develop their careers. Here in the States—and in many other parts of the world—it’s much more difficult, so I would like to collapse that barrier wherever possible.”

The open source software she’s referring to, which Kurdali has worked with for more than a decade and become a preeminent expert in, is called Blender. Like some of the better-known open source products like the Internet browser Mozilla Firefox and the GNU/Linux operating system (which also spawned the mobile Android platform), Blender is a free, downloadable suite of programs that has evolved largely through user input, thanks to its publicly available source code. Originally developed by Ton Roosendaal while he was in the employ of the Dutch animation studio NeoGeo, Blender briefly existed as shareware in the late ’90s until Roosendaal’s NaN company went bankrupt in 2002. In the wake of NaN’s bankruptcy, Roosendaal waged a campaign to raise approximately $100,000 from the public, upon receipt of which his creditors allowed the Blender source code to be released under the GNU General Public License.

Since then, enthusiasts like Kurdali have propelled the software forward exponentially, taking it to heights that Roosendaal probably could never have dreamed of had it remained the property of a company who considered the product’s source code its primary value. Bassam began using Blender back around 2000, when it was a much more primitive set of tools than it is today, but because he was one of the pioneers of the process, his work attracted interest when seen by Roosendaal at the roving annual computer graphics trade show SIGGRAPH. The Blender creator expressed admiration for Kurdali’s relative mastery of the medium, and the two joked about how cool it would be to make a movie with the software.

“I was doing animation in Blender very early, when no one else was, and when Blender wasn’t really very good for doing animation,” Kurdali recalls. “It was actually very hard to do animation with Blender—you had to do everything using undocumented hotkeys—there were no menus like there are now. It was very much like ‘press a key on your keyboard and see what happens,’ but I was just motivated to do it at the time.”

Thinking their Sigraph conversation was mostly just a pipe dream, Kurdali returned home, but was surprised when, a short time later, Roosendaal contacted him.

“I got an email from Ton saying, ‘Hey, I got the funding—when can you start?'”

Such funding is not so scarce in places like Europe or Canada, where government budgets aren’t as strained as they are in the U.S., and aren’t in constant competition with, say, the Defense Department, for government support. Many pioneering and groundbreaking projects in the arts are frequently incubated with government money outside the States, and the results can be surprisingly successful.

“This year,” Bassam tells me, “I think three out of the Oscar-nominated [animated] film shorts were funded by the Canadian National Film Board.”

*

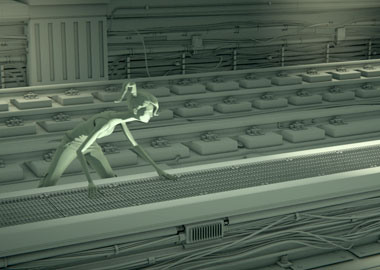

So, for a time, Kurdali was off to Amsterdam, where he became the director and principal animator of his first film short, Elephants Dream, the first HD DVD printed in Europe. Produced by and for the Blender Foundation, the film was released in 2006 and served as a mighty resume item for Kurdali and his collaborating animators and as a demonstration of the software’s much-improved features and capabilities. The modern version is a complete 3D modeling and animation suite with additional tools including a game engine. It has been used to generate finished content and/or animatics (rough, animated storyboards) for The History Channel, Spider-Man 2 and the 2010 feature The Secret of Kells, which was nominated for an Oscar for Best Animated Feature. Elephants Dream, because of its open license, has wound up in other software companies’ trade show displays, on television and even in a distinguished MoMA exhibit called Design and The Elastic Mind, a show curated by architecture and design guru Paola Antonelli (http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2008/elasticmind/).

Other projects have been incubated within the Blender Foundation community, including the shorts Big Buck Bunny and Sintel (produced by Roosendaal and directed by Pixar artist Colin Levy). A new open movie project, Mango, was announced by the foundation in the fall of 2011.

Kurdali is a big proponent of open models in both source code and distribution, especially for animated shorts.

“I really like short animation as a format and a medium,” he states. “Maybe better than feature animation, and it’s sort of the perfect place to start with this open concept, because with almost anything else, you’re going to encounter this resistance—there’s an established way of ‘this is how you’re going to make money with this stuff, this is how you’re going to distribute it,’ et cetera. Short animation kind of follows the same model, but with one exception: it doesn’t make money. They’re mostly calling cards and not a goal unto themselves, and yet people still try to distribute them through traditional means—which isn’t really distribution at all, it’s restriction, if you’re not just putting it out there on the Internet—but still for no profit.

“It seems suicidal to me, and if we can establish a sustainable model where productions like this are crowd-funded prior to doing the work, we might be able to make the medium into something that’s actually profitable.”

*

Tube, the first open movie animated project to be produced outside the Blender Foundation’s umbrella (“outside the mothership,” Slavitskaya says), is based on the Epic of Gilgamesh, a Mesopotamian poem that’s one of the oldest surviving examples of literature. Originally told in Sumerian and later Akkadian and Babylonian, the story is recorded on stone tablets that date back past 2,000 B.C., and contains many direct parallels to later biblical stories like the Garden of Eden and the Great Flood.

“I’ve been collecting translations of Gilgamesh for a while,” Bassam says. “There are a few things that I find really fascinating about it. One of them is just the way it gets to us—the whole story of having this big thing that comes to us on these little fragments of tablets that are in a language no one understands, and all these translators put it back together. That story in itself is super fascinating.

“The other thing I find to be really gripping about it is that it pre-dates biblical stories, but it almost seems more… modern to me, in some ways. There’s this king, Gilgamesh—who’s a demi-god, actually—who’s seeking the secret to eternal life, which is somehow in the possession of this Noah-like character, and then he just… doesn’t get it. He has it in his grasp numerous times, and then he just kind of fumbles it.”

“It’s also seeded a lot of things,” Fateh adds. “We know elements of it from the Bible, Hercules mythology, The Odyssey—its story is implicit as well as explicit.”

Bassam and Fateh have debated whether the story is more mythical or humanistic, whether historical or presciently utopian. Fateh says the tyrannical king Gilgamesh (in the story), whom the common people have “inflicted their friendship upon” is forced, through having to confront his own mortality, to “join humanity instead of setting himself apart from it or above it.”

They generally agree that the object of the story is not in fact the object of the protagonist’s quest; it’s more a by-product of it. It is this subtlety of author intent that endears the tale to them and perhaps what makes it feel more “modern” to their sensibilities.

“It’s a tale where the hero actually fails in his quest instead of succeeding,” Bassam reflects, “but that failure is somehow the important thing.”

If all goes according to plan, Tube will be finished by December or January. Slavitskaya describes their work on it as being done in “almost all of our time, [while] doing paying work in our spare time, as absolutely necessary.”

Back at the Nerdodrome, the topic of conversation shifts to the technological superstructure behind Bit Films and URCHN.

“This work requires a lot of computing power, and a render farm—giant racks of machines to do the computing labor that is required,” Slavitskaya says. “All of us have the shared problem of how to make independent animation, so the idea is that this is a space that can foster that kind of activity, and [Hampshire] offers us its facilities… in exchange we conduct our work here and take on students, and it’s a very kind of… fertile space. In traditional funding terms, just the use of the render farm could be equivalent to—oh, $50,000 worth of budget or so.”

Chris Perry lays out the specs of Hampshire’s render farm or “cluster,” describing the aggregate beast as 332 cores with a total processing power of 384 GB of RAM. “Helga,” a customized, web-based production management system, allows multiple people to log in from anywhere and track where various parts of the project are at in production. It also helps keep track of what are known in the animation biz as “assets,” essentially giant chunks of already-processed information that, in open source communities, can be used again in different projects. An asset might include all the modeling, animating, texturing, lighting, rigging and rendering information that goes into an object or scene in a game or movie production.

“Assets like Tube’s train car [a notable animated object in the short], for example, are really valuable, and I think that’s a big part of why its Kickstarter campaign has been so successful,” Perry explains. “The rewards it gives out [to encourage Kickstarter funding pledges] include this information [on a DVD], these assets, and there’s a big community of animators out there to whom these things are very desirable.”

Even though building a library of such assets can theoretically shave thousands of “human-hours” from a project, Perry cautions that because of the speed with which animation software evolves, there’s only so much you can rely on what he calls a “digital backlot.”

Kurdali agrees, explaining that because some of the assets use advanced, cutting edge features of the most current versions of the software, they tend to “break” with software updates.

“It’s the one downside of open movies. You have these character rigs—they’re kind of like puppets, so they’re complex machines that make the character workable by an animator, and they depend on these tiny little mathematical things that sometimes change, though sometimes you can update and fix them.”

“Data is not immortal,” Slavitskaya summarizes, with the patient smile of someone who’s had to shrug off losing gigabytes of data or hundreds of hours of work many times before. “You have to keep making new work.”

Is Blender executable on a typical, 10-year-old laptop? Absolutely, say Fateh and Bassam.

“A lot of my commercial work I do all on my old Thinkpad,” Bassam says. “As long as you keep it somewhat simple, it’s doable.”

“And there’s a thing out their called renderfarm.fi—we love the Finns—that’s basically a crowd-powered render farm,” Fateh tells me. This still relatively new experiment, essentially a hive-mind CPU-sharing platform, allows 3D artists to use a network of computers’ processing power to do their heavy lifting on renders, rigging and other RAM-intensive tasks. “It’s kind of like SETI at Home [a network that looks for extraterrestrial life in the universe], if you’ve heard of that. Basically, when you’re not using your computer, it goes onto the network as available RAM.”

*

The 3D modeling aspect of software like Blender, combined with the open source concept, also touches on 3D printing, also sometimes known as additive manufacturing. The open source model, if extrapolated into this cutting edge universe, might ultimately result in some sort of global architectural Wikipedia of three-dimensional designs where people anywhere can access and produce things without the cost of designing them or having to assemble them in any traditional sense. The implications are mind-boggling.

“We live in a digital age, where there’s this zero-cost copying,” Slavitskaya expounds, “so we’re interested in creative models that are based on the ease of reproduction rather than fighting it [as many ‘anti-piracy’ movements have attempted]. We think that this could actually be really significant if we do things that really invest in the commonwealth and encourage the growth of a kind of repository of tools and data that people can do all kinds of things with.”

Bassam describes his experience of designing a 3D snake swallowing its own tail that was 3D printed/manufactured by a surprisingly affordable printer. Fateh mentions that another of their Kickstarter “rewards” for helping to fund Tube is actually a 3D print of Gilgamesh.

“Actually,” she says, “a little while ago we took a tour of the M.I.T. media lab. Now, not only can you make prototypes from metal as well as plastic with no injection molding, you can 3D print entire working machines like a clock, with all its pieces and gears, and you don’t have to assemble it.

“The guy we were with showed us a flute they had made—an actual musical instrument—but he said it didn’t work because of a ‘resolution problem,’ and I just had this… kind of a moment. I’m going to remember this as a crystallization of our modern condition, where physical objects have resolution problems.”