It was a spontaneous idea: climb the scaffolding against the north wall of the cathedral that was unvisited by residents and tourists, enter the cathedral, and take whatever could be easily grabbed. Tag the sculpted golden stones with an irreverent and cryptic signature in spray paint for good measure. Lithe and daring, they figured they could scale the wall and walk ledges to the lowest point of vulnerability: the Chagall windows that dominated the choir chapels. They would remove a square of glass just large enough to squeeze through, cut through any metal in the window with bolt cutters, and then shimmy down to the immense, dark space. There was no alarm system. They would quickly gather the pieces that were removable and small: brass crowns from sculptures of saints, medallions displayed in cases in the crypt: anything loose and metal. It was bound to be worth something.

It was a spontaneous idea: climb the scaffolding against the north wall of the cathedral that was unvisited by residents and tourists, enter the cathedral, and take whatever could be easily grabbed. Tag the sculpted golden stones with an irreverent and cryptic signature in spray paint for good measure. Lithe and daring, they figured they could scale the wall and walk ledges to the lowest point of vulnerability: the Chagall windows that dominated the choir chapels. They would remove a square of glass just large enough to squeeze through, cut through any metal in the window with bolt cutters, and then shimmy down to the immense, dark space. There was no alarm system. They would quickly gather the pieces that were removable and small: brass crowns from sculptures of saints, medallions displayed in cases in the crypt: anything loose and metal. It was bound to be worth something.

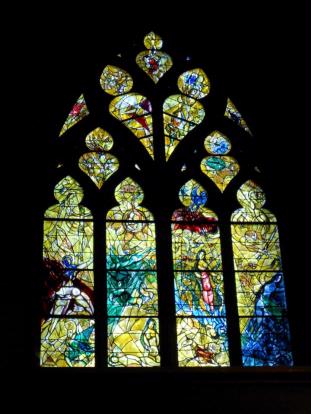

Perhaps. But not worth anything close to the damage they had inflicted on the famous Chagall stained glass window depicting, mostly in yellow glass, the story of Adam and Eve and original sin.

The culture ministry of Metz (for it was, indeed, the Saint-Etienne Cathedral in Metz where this had taken place one night in August 2008) assured the press that “experts would be able to repair the window from the fragments recovered on the site.”

Who are the experts who can reliably piece together a precious stained glass window designed by a world renowned artist? This is not verified by research, but the illustrious Jacques Simon Workshop in Reims would have been the natural choice, as this workshop was the chief collaborator with Marc Chagall—the fabricators of his designs—for major stained glass projects he was working on in various countries from 1957-1974, including Notre Dame Cathedral in Reims, the Peace Window at the United Nations in New York, the Church of Tudeley in England, the Chapel in Union Church at Pocantico Hills in New York, and the windows designed for the Cathedral at Metz.

The respected Atelier Jacques Simon has been in business since 1640 and is the seventh-oldest family firm in France. It is run now by 12th generation artists in the medium of stained glass (vitraux). The workshop’s collaborations with twentieth-century artists began in the late 1950s and were spearheaded by Brigitte Simon (daughter of Jacques Simon). Their first work of this nature brought to glass the imagery of painter Jacques Villon (also in Metz Cathedral).

The studio technique used on the windows by Villon and Chagall is acid etching on flashed glass, which is clear glass with a veneer of colored glass. The etching process for glass is basically the same as the process used for metal plates in printmaking: an acid-resistant ground is applied to the glass, and a design is carved, drawn with a tool that will scrape away the resist. This is then placed in an acid bath, and the acid eats away at the exposed carved areas. Subtle tonality—color fields representing the spectrum of transparent color between the color of the veneer and the clear base glass–can be achieved with extremely skilled and careful monitoring of the process. Black enamel paint is used on the Chagall and Villon windows for the detailed work (a technique of monochromatic painting called grisaille).

The short film A Palette of Glass: The American Windows of Marc Chagall (c. 1977) features Marc Chagall and Charles Marc, a principal and lead glass artist from the previously mentioned Jacques Simon workshop, on windows designed for the Chicago Art Institute and dedicated in 1977. Charles Marc on the making of the stained glass begins at about 10:42, footage with Chagall painting on the constructed windows begins 17:27.

And what of the Biblical subject matter of Chagall’s four-paneled lancet windows in Metz Cathedral? The dominantly yellow series chronicles the story of Adam and Eve and their expulsion from Eden.

The dominantly blue series depict more scenes from the Old Testament: Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac, Jacob wrestling with the angel, Jacob’s dream, and Moses and the burning bush:

And how interesting that an iconic Jewish artist of the twentieth century, one who fled to the U.S. from Nazi-occupied France during World War II, would return to France and create monuments of Christian art (in the Reims Cathedral, the windows’ subject matter includes the Madonna and child and the crucifixion). Perhaps the entire Judeo-Christian religious tradition had validity for Chagall; or possibly his artistic soul worked in a less specific way to illuminate the animating principle of life. In Chagall’s own words:

“For me a stained glass window is a transparent partition between my heart and the heart of the world. Stained glass has to be serious and passionate. It is something elevating and exhilarating. It has to live through the perception of light. To read the Bible is to perceive a certain light, and the window has to make this obvious through its simplicity and grace . . ..”

1962, from the dedication of the his windows designed for Hebrew University’s Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem.

If I were a novelist I would be tempted to recreate the story of the petty thieves in 2008 who crept into the cathedral via the broken masterpiece. One might get an infection from a glass shard of a particularly toxic blend of “ancient blue” made from cobalt and lead. One might be haunted by dreams of serpents and apples. Or would I reach back further and learn more about the art of the cathedral and its illustrious makers? Here’s hoping that Geraldine Brooks has at it.

Images, top to bottom:

Chagall’s Adam and Eve window, Metz Cathedral, photo by Hayley Wood

Detail from Chagall’s Adam and Eve window, Metz Cathedral, photo by Hayley Wood

Chagall’s Old Testament stories window, Metz Cathedral, photo by Hayley Wood

Sketch by Chagall, preliminary design for window at Chichester Cathedral in England, courtesy of the Jacques Simon Workshop web site