The book Whitey begins with a scene that sounds like something from a Scorsese movie. Authors Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill use court records and other sources to construct the story of a murder, invoking the point of view of the victim, Debbie Davis.

The setup they describe was brutal. Davis, longtime girlfriend of Boston mob boss Whitey Bulger’s confederate Stevie Flemmie, was invited to an empty house Flemmie had just bought for his parents. Flemmie arrived for their rendezvous with Bulger, who’d long found Davis problematic—she knew a lot of the details of Flemmie and Bulger’s activities, including the name of an FBI agent they’d corrupted, and talked about what she knew too freely.

Bulger strangled Davis while her boyfriend watched.

With that story, Lehr and O’Neill immediately establish the depravity of their subject. To those of us who reside in the Bay State (and remember Whitey’s brother Bill as a state politician and president of the UMass system), it can be easy to forget that Whitey Bulger’s story is more than a homegrown tale—that his shadow looms large on the national stage, too.

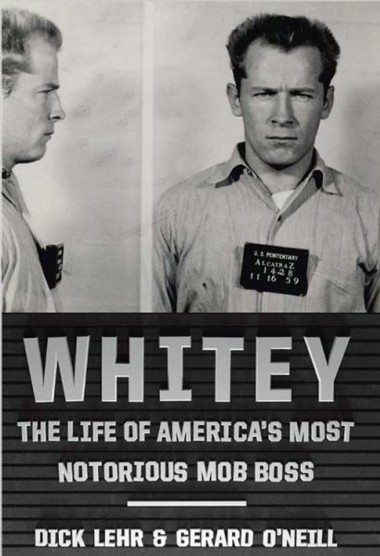

Whitey is a monumental book of research and storytelling, delivered by two writers who are long-established as experts on Boston history. Lehr, a journalism professor at Boston University, is a former Boston Globe reporter, and Pulitzer Prize winner O’Neill was editor of the Globe’s investigative team. With Whitey, the pair complete a trilogy about Boston’s organized crime world. All the same, this exhaustive volume stands alone for all but those who want every gory detail of a long and sordid career in crime. One of the pair’s earlier volumes, Black Mass, details Whitey Bulger’s remarkable corruption of the FBI’s Organized Crime Squad, which, for almost two decades, left Bulger unrestrained in his activities, from mere bookmaking to a slate of murders.

Though the jacket flap copy sensationalizes Bulger in stark, cartoonish terms—he’s a “monster” with an “insatiable hunger for power and control”—Whitey is an engaging read that employs both deft storytelling and more standard biographical approaches. The amount of information in its pages is staggering, and no wonder—at 83 years old, Bulger boasts a story that takes a while to tell.

The book begins with Bulger’s earliest days, when he went from school dropout to being a Southie tough known for existing outside the constraints of the law. It’s hard not to think, again, of Scorsese’s Goodfellas as you read tales of a young man flaunting new cars in a neighborhood where no one owned cars, showing up with snazzy clothes and the girlfriend all his peers wanted.

Lehr and O’Neill have to sift through viewpoints in those and other stories as they search for fact, and they explain their choices in extensive notes and references at the end of the book. The facts they dig up don’t seem to support the Robin Hood-esque, misunderstood hero version of Bulger’s story that once reigned. Instead, they portray him as ruthless and psychopathic, a criminal primarily obsessed with keeping himself out of harm’s way.

Not surprisingly, it’s the scenes of mayhem that Lehr and O’Neill dramatize that draw the reader through a book. There’s something hard to pin down that makes amoral characters fascinating, and that fascination gets a workout in Whitey.

Take, for instance, the book’s description of the killing of a Bulger associate named Tommy King. The hit was a mind-twister; King was given a gun full of blanks to help with the supposed killing of another gangster. Instead, “…before the car even reached the rotary at Preble Circle, Johnny Martorano quickly shifted forward and put his pistol to the back of Tommy King’s head. Tommy King pitched forward into a heap. He was dead, and the car’s interior on his side was spattered with blood and brain matter. Whitey hated messes, but by using a stolen ‘boiler’ the mess was someone else’s, not his.”

The stories go on seemingly ad infinitum; Bulger’s long career was, despite his distaste for messes, a messy one. The book is solidly grounded, but well dramatized. Its prose is not flashy, but is perhaps all the more effective for its description of a life spattered with blood and unhindered by morality. Similarly, its reliance on precise descriptions of Boston streets and neighborhoods makes it ring true as a Massachusetts tale. Bulger is drawn as a thorough Southie, the product of his place and time, a place and time that’s just down the road.•