“The first rule is this: you can’t say ‘I liked it’ or ‘I didn’t like it.’ This isn’t useful information—useful to you, but not to anybody else.

“And you can’t say ‘I disagree’ with what someone else just said. This is not a debate. There’s no right or wrong in the play. We don’t want to start arguing, we want to hear what everybody feels and thinks.”

Byam Stevens is standing in the aisle of a chartered bus heading back to the Valley from a playgoing day trip to New York City. He’s addressing 33 patrons of the Chester Theatre Company, prepping them for a discussion of the show they’ve just seen. Apart from the unusual venue, this is something that happens after every CTC performance during the summer season, and after each show during the company’s annual theater junkets to London and Dublin.

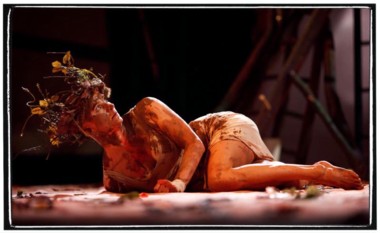

“We’re obviously not going to a Broadway show,” Stevens, CTC’s artistic director, told me on the drive down, referring to his company’s—and his audience’s—preference for small-scale, large-issue contemporary theater. “We’re going to see something that most people probably wouldn’t find on their own.” That something is The Wild Bride, a wildly applauded production by Kneehigh, an English company rooted in physical theater and collective creation. It’s a free (very free) adaptation of the Grimm (very grim) fairy tale known as “The Handless Maiden,” relocated to the rural South of Depression-era America, drenched in country blues and narrated by the Devil himself.

Stevens begins the dialogue by asking, “What was the first thing you saw when you came into the theater?”—in this case, an open stage dominated by an abstract tree topped with a large round mirror. These first impressions, he says, are keys to the tone and style of a play. “This is theater,” he says this set was telling us. “We’re not going to try to fool you. No, we’re going to engage your imagination.” One of the bus riders chimes in, “The mirror tells us it’s going to be a fantasy.” Another adds, “And a reflection of ourselves.”

With these and other leading questions, Stevens is prodding his audience to be alert to all aspects of a production. “How do sets, costumes, music and so forth tell us what the play’s about before we hear any text?” This is part and parcel of an initiative he launched at Chester a couple of seasons back called Freeing Your Inner Audience—talkbacks-cum-symposia on “the bones” of a production, from sets and lights to staging and style.

Sure enough, Stevens’ ground rules produce a deeper exploration of responses to the play—“a richer tapestry,” as he puts it—than a simple airing of opinions. The discussion ranges over themes of good and evil, suffering and resilience, why the title role was played by three different women, the function of storytelling in our culture and the importance of visual storytelling in this production.

On the latter topic, one patron comments, “It captures the child in us. And my child was delighted.”•

The next CTC New York trip will be on May 11, to see the American premiere of These Halcyon Days by the acclaimed Irish playwright Deirdre Kinahan. 413-354-7771 or chestertheatre.org for info.

Contact Chris Rohmann at StageStruck@crocker.com.