Michael Kogut and Mark Mullan have spent the past several months traveling around Springfield making their case for why city voters next week should reject MGM’s proposed $800 million casino in the South End. Often they find themselves in the casino company’s shadow.

When the two went recently to speak to a neighborhood association, they learned that MGM had sponsored a community cookout for the group not long before. On June 25, the day of the special Senate election, company representatives were at polling sites handing out doughnuts and lemonade and bottles of water bearing MGM labels.

The company says it’s held hundreds of community meetings around the city, and it’s donated tens of thousands of dollars to civic causes, from the South End Community Center to last week’s Fourth of July fireworks. Then there’s the sheer volume of public relations material and advertising MGM has paid for in the city, and the free promotional help it’s receiving from City Hall, which says the casino’s promise of thousands of jobs and millions in tax revenue will transform the struggling city.

To describe a lopsided contest as a David-versus-Goliath battle is to employ the hoariest of political clichés. But sometimes even the stalest cliché is right on the mark: MGM Resorts International owns and operates 20 casinos in the U.S., including some of Las Vegas’ largest, and another three in Asia; it reported $6 billion in revenue in 2011.

In April, the Boston Globe reported that the company had already spent $10 million on its Springfield campaign, including $1 million on advertising—and that was before its recent intense push leading up to next week’s ballot question. It’s hired political lobbyists and media firms to advance its cause, including top Boston firms and former Springfield state representative Dennis Murphy. (MGM, through a spokesperson, declined to comment for this story.)

On the other side of the battle is Citizens Against Casino Gaming, an all-volunteer group working with a budget that Kogut describes as “a few grassroots thousands.” (The group, a ballot question committee, does not have to file campaign finance reports until January.) Working with a handful of like-minded organizations, including the Greater Springfield Council of Churches and the Episcopal Diocese of Western Mass., it’s swimming against a tide of pro-MGM rhetoric to get out its message: that rather than save Springfield, a casino would only exacerbate existing socioeconomic problems in the city, and create a host of new ones.

“I just see this as something that’s going to kill the city,” said Mullan, a doctor who grew up in the city and practices in the North End.

On July 16, Springfield voters will be asked to approve a host community agreement negotiated by City Hall with Blue Tarp reDevelopment, MGM’s development arm for the Springfield project. (In negotiating the MGM deal, the Sarno administration simultaneously rejected a competing proposal from Penn National to build a casino in the North End. A third company, Ameristar, which had its eye on an East Springfield site, had already dropped out of the running several months earlier.)

The MGM agreement calls for an 850,000-square-foot project that would include, in addition to casino space, a 250-room hotel, adjacent retail, office and restaurant space and a public skating rink. It promises 2,000 construction jobs and another 3,000 operations jobs, 2,200 of them full-time, once the casino opens, with quotas for hiring women, minorities and veterans.

MGM pledges to fill at least 35 percent of those jobs with city residents and to provide job training programs and subsidized, on-site daycare for workers. It also commits to various payments to the city, including alternative tax payments and development grants. In total, the agreement calls for $15 million in advance payments to the city and projected annual payments totaling $26 million. (A link to the full agreement can be found at www.springfield-ma.gov. The opponents’ website is www.citizensagainstcasinogaming.com.)

Mayor Domenic Sarno, who is leading the pro-casino “Yes for Springfield” campaign, recently said at an MGM rally that the project would bring “good jobs, a revitalized downtown and a better tomorrow for Springfield.” Sarno did not respond to an interview request from the Advocate.

The City Council approved the agreement, with minimal debate, shortly after its release. But state law requires that city voters approve the plan, too—hence next week’s ballot question.

If the project wins at the ballot box, it will compete with two other proposals—one in Palmer, the other in West Springfield—for the sole casino license to be awarded in Western Mass. by the state Gaming Commission. Still, the Springfield proposal has garnered by far the most attention, in large part due to City Hall’s enthusiasm for bringing a casino to the city. The project also has strong backing from organized labor, and a number of community groups, including the South End Citizens Council, have endorsed MGM’s plan.

This is not to say that there’s universal support for a casino among city residents by any means. But there hasn’t been the same degree of organized opposition there was the last time Springfield grappled with the casino question, back in the mid ’90s. In 1995, city voters elected the pro-casino Mike Albano as mayor but defeated a casino ballot question. Ultimately, it was a moot issue, as the state didn’t pass a bill legalizing casinos until 2011.

Kogut, a lawyer who once worked in the Mass. Attorney General’s office, began organizing against a casino last fall. He was frustrated, he said, by the lack of balanced information about the project reaching the public—a problem heightened by the fact that the city’s daily paper, the Republican, had a financial interest in Penn National’s proposal.

Instead, Kogut said, residents have been fed a steady stream of “fluffy advertising” from the media and City Hall alike. “It looks like the city has been bought and sold by MGM,” he said. “We have a mayor who’s absolutely giddy over this.”

He and Mullan also criticized the mayor for incorporating $5 million in payments from MGM in the recently approved fiscal 14 budget—$4 million of which is not guaranteed unless the company wins a casino license. Without that money, Sarno said, the city would have to lay off 100 employees and cut services—a rather pointed warning that many see as an attempt by the mayor to strong-arm residents into approving the ballot question.

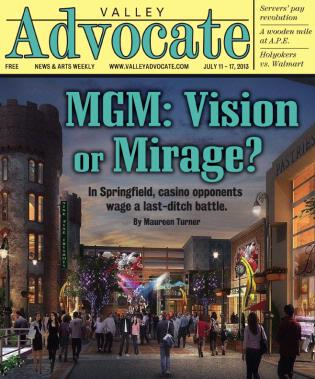

As the election looms closer, Springfield residents are being swamped with gorgeous images of the prospective casino, with shiny new buildings, old-fashioned trolleys running down Main Street, beautifully landscaped courtyards, smiling people strolling along impeccably clean streets.

But Kogut and Mullan offer a different, and darker, vision: a scaled-down “box” casino cut off from the neighborhood. And, perhaps eventually, a vacant building.

“This financial model is going to fail,” Mullan said bluntly. For one thing, he noted, New England and upstate New York are fast becoming saturated with casinos and “racinos.” Meanwhile, the two oldest casinos in the region, Connecticut’s Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun, are struggling. In light of that competition, he and Kogut question whether MGM will ever be busy enough to support the number of jobs and the level of adjacent development it’s promised, or profitable enough to provide the financial bonuses it’s offered the city, from underwriting support for local theaters and sports teams to contributions for projects such as improvements at Riverfront Park.

Stiff regional competition would also mean that the casino would not draw out-of-towners to Springfield, as many hope, but would instead rely on business from local residents—specifically “the people who can least afford it,” including the elderly, the poor and unemployed, Mullan said.

“I’m very against an urban casino, especially in a city like Springfield, with all its socioeconomic problems,” Kogut said. Gambling is a “parasitic industry,” he said, and a Springfield casino would lead to increased crime and gambling addiction and lower property values. It also would hurt local businesses, the opposition says; while MGM has vowed to encourage casino visitors to patronize nearby stores and restaurants, Kogut and Mullan are highly skeptical, noting that the typical casino model is to draw in customers and keep them there to spend their money at the casino’s restaurants, theaters and shops.

The MGM project also poses a threat to the city’s broader economy, they say. “The city’s economic development is virtually paralyzed because the mayor had chosen to make this his one and only economic development project,” Kogut said. Not only is the city not courting other businesses, he said, but those businesses are unlikely to want to move to downtown Springfield until they see what comes of the casino project. The casino, Mullan added, also would dissuade middle-class people from moving downtown—one of the main priorities identified in a revitalization plan done for the city by the Urban Land Institute a few years back.

As he talks to people about the ballot question, Kogut said, he doesn’t come across many “rabid proponents,” outside elected officials and others with a stake in the project.

Instead, he said, he sees many people simply resigned to the inevitability of a Springfield casino—a feeling that’s intensified by the lack of critical analysis of the project on the part of city officials. Mullan described the meeting where city councilors approved the MGM agreement as “truly a dog and pony show.

“They didn’t even question it,” he added. “They were more concerned about getting home to watch the Bruins game.”

That lack of engagement, coupled with the Sarno administration’s aggressive promotion of the project, leaves many people unwilling to stick their necks out to oppose the plan publicly, Mullan suggested. But in the privacy of the voting booth, he and Kogut hope opponents will make their voices heard.•