One of the great and beautiful mysteries of art is its timelessness. How we view it, of course, has changed through the centuries—we’ve gone from caves to churches to museums, from worshiping masses singing together to silent museum-goers, each with an audio program whispering in his or her ear. And certainly, the art looks different. Sometimes, in fact, it doesn’t look like anything at all.

And yet it continues to move us, touching us on some level unreachable by almost anything else—love and death might be the only other things that have access to that part of our hearts. A three-minute pop song can bring out our tears as readily as the most grandiose symphony, and while a Rothko and a Rembrandt may seem worlds apart, I’d gladly stand for an hour in front of either of them. Each, in some indescribable way, taps into some deeply elemental well inside of us, and it’s primal enough that we can pair a 19th-century tone poem with space exploration—just ask Stanley Kubrick, who did it, famously, in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

He might also tell you that few of our arts are more immediate than film. When we see another human on the screen, we feel the movement as they walk down a street or struggle under a weight. A first kiss on film is somehow more alive than that same kiss in a novel, or even, paradoxically, on stage; something about the sheer scale of cinema—those towering faces in the dark!—makes it at once more familiar, more intimately felt, then it is anywhere else. For all its glamour, cinema has always essentially been about reminding us what it feels like to be alive.

All of which leads me to Final Cut—Ladies and Gentlemen. This film, from Hungarian director György Pàlfi (Taxidermia), is both unlike anything that has come before it, and exactly like those things. It is, in fact, a film made up entirely of other films.

Drawing on over 450 films that span the entirety of cinematic history, Pàlfi’s finished piece pulls these tiny snippets—sometimes just a few seconds of film—into one coherent story of Boy Meets Girl. Over the course of his film those two characters are “played” by just about every film icon you can imagine. It’s an idea used, on a much smaller scale, to great comic effect in Steve Martin’s 1982 film Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid: in that movie, the old clips were used more as straight men for Martin’s inspired riffing on the hardboiled detective tropes of film noir.

In Final Cut, the clips are still used to tell a story, but this time—it’s a hard feeling to describe—the story is our own. In the trailer alone (which you can view at vimeo.com/71065220), the male lead is shared by Charlie Chaplin, Robert De Niro, Jon Voight, Woody Allen and many others. Yet so seamless is Pàlfi’s editing that it reads as the same character seen through shifting lenses, an everyman in changing fashions. He might be Rembrandt or he might be Rothko, but in the end the name doesn’t matter: he is us.

And now for the bad news: you may never get to see this film. Although it has popped up now and again at film festivals over the last year, it has a fatal flaw: due to the insurmountable paperwork, financial obstacles, and general drudgery of bureaucracy, Pàlfi has never secured the legal rights to use these film clips, virtually guaranteeing that it will never have a for-profit run anywhere. For now, it is a catch-as-catch can affair, so I tell you, if you have the chance to see this film, grab it.

****

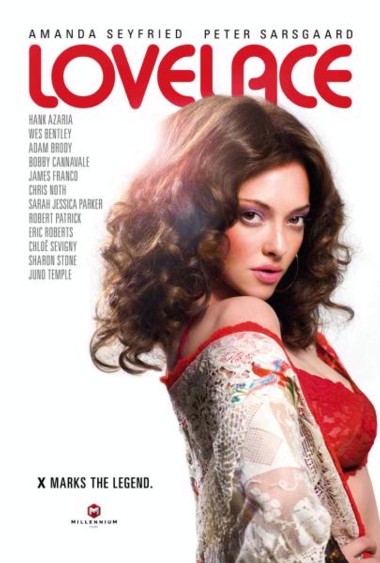

Also this week: Amherst Cinema screens Lovelace, the story of pornography’s first big-screen star. It features Amanda Seyfried (Les Misérables) as Linda Lovelace, who shot to fame after the unlikely success of Deep Throat. That film—a scripted, theatrical (if pornographic) feature that seems almost quaint by the anything-goes standards of today’s Internet age—landed like a bomb in 1972, becoming such a pop culture touchstone that the name was adopted for Woodward and Bernstein’s famous Watergate informant.

For Lovelace—born Linda Susan Boreman, the religious daughter of a New York City policeman and a controlling mother—her brief fame was an unhappy affair. While she at first embraced her newfound celebrity, becoming an outspoken advocate for sexual freedom, she would later charge that her husband at the time, Chuck Traynor (a porn hustler played here by Peter Sarsgaard), had in fact been an abusive pimp who forced her at gunpoint to perform the acts that made her famous. “When you see the movie Deep Throat, you are watching me being raped,” she would later testify.

By the 1980s she had turned her back on the industry and become a leading voice in the anti-pornography movement, but problems in her personal life continued to plague her, leading to a second divorce, hepatitis and a liver transplant, and an early death at age 53.•

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.