Eight or 10 pages into Holly Black’s just-released young adult novel The Coldest Girl in Coldtown, you will be happily doomed. Black does a masterful job of making an unimaginably weird world seem viscerally real, and by the end of the second chapter she’s raised the emotional stakes to fever pitch. Good luck putting it down, no matter your age.

It bears noting that yes, there are vampires. Plenty of them. But this is no Twilight melodrama, no ’50s saga of caped Transylvanians. This is instead a story of childhood giving way to adulthood, of teenagers making their way through a complex and dangerous world. Black delivers a powerful elixir, mixing inner landscape with the curiosities of a world gone undead with such a deft hand you won’t even notice as the teeth sink in.

For Black, vampires are a longstanding obsession, one that dates back to her seventh and eight grade years. Though it may seem like a tough time to ride the vampire train now that some of the blood-sucking fervor of recent years has subsided, Black takes the long view. “There’s never been a good time to write about vampires. They’re either so over you’d be crazy to do it, or so popular you’d be crazy to do it. Vampires are always re-inventing themselves—it’s what they do.”

It also seems true that a highly original take such as hers is not dependent on the waxing and waning of trends.

Black’s deft conjuring of her book’s fantastical world is not just a happy accident. Ask her about it, and she delivers well-considered, sharply defined ideas. “I think you have to wind up describing the real world, such that when you’re describing the fantastic world, the weight is right,” says Black. “One of the things I noticed, particularly when I gave a reading with other YA [Young Adult] writers—both fantasy writers and realistic—is that fantasy writers have a lot more description. A fantasy world must be described well—if you don’t describe the fantastic world the same way as the realistic world, it doesn’t feel as right. It’s also a matter of not making it too perfect, making the world a little dirty, a little messy.”

And it is indeed that kind of messiness that offers a ring of truth and draws you helplessly in. Early on, she offers a glimpse into the thoughts of the protagonist (Tana) that places her firmly in a familiar world: “When Tana was six, vampires were Muppets, endlessly counting, or cartoon villains in black cloaks with red polyester linings. Kids would dress up like vampires on Halloween, wearing plastic teeth that fitted badly over their own and smearing their faces with sweet syrup to make mock rivulets of cherry-bright blood.”

Passages like that, passages that would work equally well in a work of realistic fiction, provide the kind of investment into Tana that allows episodes of the fantastical to seem just as real: “Tana remembered the way it felt, the endless burn of teeth on her skin. Even though they weren’t fully changed, the canines had still bit down like twin thorns or like the pincers of some enormous spider. There had been the soft pressure of a mouth, and pain, and there had been another feeling, too, as though everything was going out of her in a rush.”

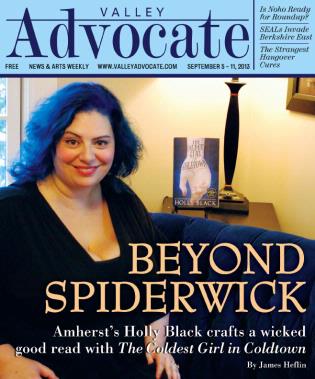

Holly Black projects just the kind of image you might hope she does if you’ve read any of her many works of darkly fantastic fiction for young adults or middle-grade readers. She and husband Theo Black inhabit a smart Tudor-esque house on a hill in Amherst, and the place possesses a woody, comfortably Gothic charm. As she chats in an imposing chair in her living room, a gold skull wearing headphones looks on. A hairless, exceptionally friendly Sphinx cat brushes by.

Black speaks quickly, with only the slightest occasional hint of her native New Jersey in her voice. She’s got a ready laugh and an energetic eagerness to talk books. Her hair’s blue, her dress black.

Black seems to echo the nimble magic of her many works, from the blockbuster Spiderwick Chronicles she co-created with Amherst illustrator Tony DiTerlizzi to her Curse Workers series for teens.

She may have left her teenage years behind, but Black’s prose reveals a writer who seems to easily slip into a mindset that resonates with young adult readers. She says doing so is, for her, a relatively simple process: “It’s no different than inhabiting anybody’s mindset—you have to put yourself into a place where you can remember what it was like. I don’t think it’s any different.”

She adds, “Sixteen- to 18-year-olds are really living an adult life, just freshly.”

Further, she says, “I think teenage readers know what they want. They’re great readers—they read a ton, and they’re not at all shy about being clear about the things they want. They’re not shy about when it doesn’t work, not shy about when they really love stuff. Teenagers are going to school—they’re an intelligent, thoughtful audience. They’re used to having to be thoughtful about books.”

The cliches of teens staring unceasingly at tiny screens may hold some truth, but Black, like many writers, believes the changing manner of reading books is less important than the exciting role books currently play in young lives. “I think there’s always going to be a place for physical books and bookstores,” Black says. “I have an e-book reader, but it usually means I wind up double-buying so I can have the book in both forms.

“I don’t know what the future of publishing is going to look like. But I know when I was a kid we didn’t talk about going to midnight book events. There’s a generation of readers now for whom the release of books is a major event. That’s huge for me, and really exciting.”

If you’re not immersed in the booming literary worlds of science fiction or fantasy, it’s easy to find the sheer quality of Black’s prose startling. She is quick, however, to dispel the notion that her work is an exception on the fantasy shelf. “I think certainly the expectations of genre are different—there are a wide range of priorities in genre. There’s plot-heavy fantasy, there’s literary fantasy. To people outside the genre, it probably looks pretty monolithic. It probably looks like a lot of wizards and dragons,” Black says. “Once you’re inside it, you realize there’s an enormous amount of variation in the genre, and also people who transcend the genre, like Neil Gaiman and Connie Willis and [Northampton’s] Kelly Link who are read by people who don’t even know they’re reading fantasy, because of our ideas of what that means.”

In the past couple of decades, the Valley has become a remarkable center of writers and illustrators who work in kids’ and young adult books. The Blacks, like others, were drawn to the area by friends in the same field. “One day one of our friends emailed me a picture of this house and said, ‘Why don’t you guys buy this house and move here?’ We bought the place without seeing it until the final inspection.”

Black says that living here has brought her a great sense of community with other writers. “We get to keep each other honest, keep each other on track.”

In another sense, she says, it can be tougher. “You go to the grocery store, and it’s like, ‘Hey Jane Yolen, hey Mo Willems! Sorry I’m in my sweatpants!’”

Black decided to become a writer early on, in fourth grade. “Everybody draws and tells stories as a kid. I think writers are the ones who just didn’t stop, who didn’t get the memo.”

With her earliest book, 2002’s Tithe, Black explains that she didn’t necessarily think she was writing a YA novel. A children’s librarian told her the genre was no longer what she remembered from childhood. Black’s explains that YA isn’t a genre in exactly the same sense as something like Westerns or spy novels.

What demarcates YA is instead who it’s about: teenagers. For Black, the genre is sometimes further defined by what it’s not: “It’s not elegiac, not nostalgic, and not didactic.”

In a recent panel discussion, Black says, the issue of what can’t be done in YA arose. “You can’t do boring. Probably not explicit, to a certain extent. It’s not a question of content, but of treatment.”

She thinks it’s vital to “reflect the realities of teenagers, not to impose.”

Black continues, “There are high stakes in YA. It’s all about firsts—about the first time falling in love, the first time being brave. It’s a time when you make huge decisions about who you’re going to be.”

With The Coldest Girl in Coldtown, those high stakes are apparent from the first pages. Things seem huge because they truly are: Black’s protagonist, Tana, wakes up in the bathtub after an all-night party, only to find most of her companions dead in a bloody vampiric massacre. In a bedroom, she finds her ex-boyfriend tied up, and a vampire chained. High stakes indeed.•