Julius Caesar is perhaps Shakespeare’s most masculine play. Only two women in the thing, each appearing in early cameos before giving way to the all-male worlds of the Roman Senate and the battlefield. So what happens when the play is turned on its macho head by an all-female cast?

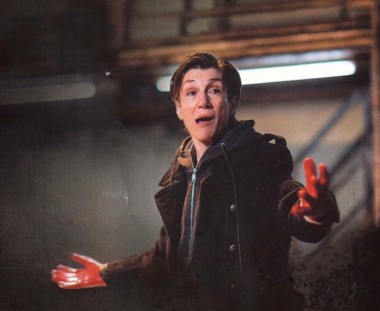

Phyllida Lloyd’s production for London’s ever-adventurous Donmar Warehouse, which came to Brooklyn this fall, is set not in ancient Rome but in a contemporary women’s prison. The theater’s steel-and-stone lobby became a prison yard, raked by searchlights, in which Shakespeare’s tragedy of conspiracy, loyalty and war was enacted by women in prison-issue fatigues (gray, not the newly fashionable orange).

From the start, I sensed a metaphor: the murderous resentment against power-hungry Caesar by Brutus and the other noble Romans reflecting the prisoners’ own desire for revenge against the guards who boss them and the system they’re trapped in. Some of the ancient/modern parallels were adroit, like the Soothsayer’s warning to Caesar, “Beware the ides of March,” read from a newspaper horoscope, and the assassination, with Caesar (Frances Barber) seated in the audience, making us complicit in the murder. Others were strained or simply peculiar, like the Soothsayer represented as a creepy little girl on a tricycle.

The actors, playing convicts playing Shakespeare, delivered the muscular verse in a variety of accents, from Cockney to Scots to West Indian—with the jarring exception of Royal Shakespeare Company veteran Harriet Walter, whose Brutus was as plummy as any old-school Shakespearean.

This was no ladylike performance, but fully as fierce and violent as any testosterone-charged action movie. And to that extent it was fascinating and even at times thrilling, with its sense of women, beaten down by circumstance and bad choices, suddenly freeing their downtrodden spirits and pent-up rage. But for all the high-concept and high energy, the metaphor didn’t quite stick.

I saw this show with a group of Chester Theatre Company patrons on one of their regular theater-going excursions to the Big Apple. Nagging questions about the framing concept came up in the discussion afterward. As Chester’s director, Byam Stevens, put it, “How did this setting serve the play?” If Julius Caesar is about rebelling against arrogant authority, why were the prisoners allowed to perform it? If it’s about the inevitable defeat of rebellion, why would they want to?

In this sense, then, the production was an example of concept overwhelming the material rather than illuminating it. On the other hand, the object of Chester’s upcoming January outing is, by contrast, an example of a concept dexterously and magnificently reanimating its classic text. Twelfth Night, from another London company, Shakespeare’s Globe, is performed by an all-male cast, the way an Elizabethan audience would have seen it.

The astonishing thing about this production, which I caught on Broadway last month, is that while it’s painstakingly authentic—from the hand-sewn costumes to the candlelit stage to the live music on period instruments—it’s not a bit mannered or musty. Indeed, it’s one of the most giddy, inventive, brilliantly acted and consistently delightful Shakespearean renditions I’ve ever seen. And here, men in women’s roles, in a play that centers on a girl masquerading as a boy and wooing a woman on behalf of the man she herself secretly loves, makes the gender-switch doubly delicious in a way Shakespeare’s audience would have appreciated.•

Chris Rohmann is at StageStruck@crocker.com and his StageStruck blog is at valleyadvocate.com/blogs/stagestruck.