In the summer of 1774 yeoman farmers, craftsmen and other members of the colonial middle classes throughout Central Massachusetts became incensed at their government–the Royal Parliament of Great Britain. Their actions would spark one of the largest political demonstrations of the Imperial Crisis and, without firing a shot, end British authority throughout most of Massachusetts.

These common farmers and tradesmen were outraged over the legislation that Parliament passed in retaliation for the destruction of tea belonging to the East India Company on December 16, 1773, what we now refer to as the Boston Tea Party. This legislation, called the Coercive Acts by those in England and the Intolerable Acts by Americans, closed the port of Boston and fundamentally changed the government structure on all levels throughout the colony. Shutting down Boston harbor caused great economic hardship. It denied not just Boston residents the “winds and seas” but merchants throughout the colony, including the Salisbury brothers who ran a thriving mercantile business with branches in Boston and Worcester and who now had to bring their goods in via Marblehead harbor at considerably greater expense.

But it was the Massachusetts Act that was the greatest threat to people everywhere in the province. This act abolished the Massachusetts Charter of 1692 and put in its place a government largely controlled by the Royal Governor who now had the authority to appoint all court officers and the Council (the upper branch of the legislature). This new legislation even restricted the holding of town meetings to once a year and required that all agendas be submitted to the Governor for approval before the meeting convened. People throughout the province were convinced that the Massachusetts Government Act was unconstitutional and designed to enslave them.

To combat these measures, most towns appointed special committees of correspondence to communicate with other towns what measures they were taking to protest the Royal government and in turn report on the actions of the Royal authorities. With these committees of correspondence, colonists created a large grassroots political system that spread beyond Massachusetts, gaining support throughout the thirteen colonies. They created and signed non-importation agreements or covenants by which they pledged not to buy or use any goods imported from the mother country. They also forced most Royal-appointed councilors to publicly resign their commissions. And they attacked the most visible representation of the government outside of Boston: the courts.

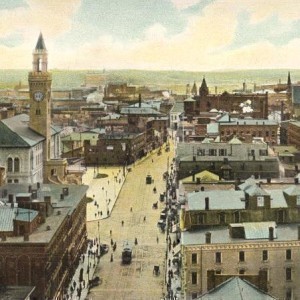

In each of the rural counties, militiamen shut down the Royal Courts. On September 6, 1774, 4,622 militiamen from 37 towns throughout the region came into Worcester, the shire town, and barred the courthouse. They also demanded that each Royally appointed official resign from office by publicly reciting a special pledge. All 25-court appointees were forced to repeat this pledge, hat in hand, so that all the members of each militia unit present could hear it. After this massive act of defiance, British authority would never return to rural Massachusetts. Instead the people would govern themselves through their own town meetings, the committees of correspondences, and through the Provincial Congress composed of delegates from each of the towns in the province. In essence the American Revolution had already begun some seven months before shots rang out in Lexington and Concord.

Now a consortium of historic organizations is commemorating this significant yet largely unknown event in our history. The organizations involved in this project called Worcester Revolution: 1774 include: the American Antiquarian Society; Preservation Worcester; American Revolution Round Tables; Second Massachusetts Regiment; Assumption College; Sons of the American Revolution; Daughters of the American Revolution, Massachusetts Society; the Tenth Regiment of Foot; Old Sturbridge Village; and the Worcester Historical Museum. Many of the original 37 towns are also involved in what is shaping up to be a region-wide celebration with lectures, exhibits, reading and discussion groups, reenactments and theatrical presentations. Programming is taking place now and will culminate in a festival of events on Sunday, September 7, 2014 in Worcester.

Some of the programming underway includes a public lecture on May 13, at 7:00 p.m. at the American Antiquarian Society and featuring Holy Cross historian, Thomas Doughton who will discuss the role people of color in Central Massachusetts played in the Revolution. The Lunenburg Historical Society will feature a talk by Barbara Fleming entitled “Pathways to Revolution” on June 5, 2014, at 7:00 p.m. which describes how Lunenburg was supporting the patriot’s cause prior to the battles of Lexington and Concord. Folks from the town of Oakham are also planning on walking into Worcester following the path that the militiamen took in 1774.

We have also organized a community-wide reading and discussion of Ray Raphael’s book The First American Revolution, which details the events of the summer of 1774. Eleven communities including Clinton, Fitchburg, Milford, North Brookfield, Paxton, Spencer, Sturbridge, Sutton, Upton, Uxbridge and Worcester are participating in this program.

And in June we launch a twenty-first century version of a committee of correspondence linking people, institutions and towns together through digital and social media.

These are just a few of the many activities planned to celebrate the Worcester Revolution of 1774. For more information about this project and a complete list of events as they take shape please go to www.revolution1774.org/