How badly do the candidates running to be Massachusetts’ next governor want the job?

For some, badly enough to sink serious amounts of their own money into their campaigns—in some cases, hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Massachusetts campaign finance law allows candidates to fund their own campaigns in two ways: through loans or direct contributions. Candidates are limited in the amount of money they can loan their campaigns: in the case of gubernatorial candidates, the cap is $200,000 a year for the primary election, and $200,000 for the general election, for a total of $400,000 a year, according to Jason Tait, spokesman for the Office of Campaign and Political Finance. They cannot charge interest on those loans, Tait said, and they can choose to forgive the debt. In addition, candidates are free to donate as much of their own money to their campaigns as they choose.

This election season, incumbent Gov. Deval Patrick’s decision not to run for re-election has led to a particularly crowded field of candidates, some of whom are investing large amounts of personal wealth in their efforts to succeed him—a situation that raises yet more questions about an issue that’s increasingly the focus of public interest: the role of money in electoral politics.

Socking your own money into your campaign does not guarantee electoral success, as history shows. In the 2006 governor’s race, Independent candidate Christy Mihos put $3.7 million of his own money into his campaign, Democrat Chris Gabrieli used $8 million of his money, and Republican Kerry Murphy Healey topped them all, spending $10.3 million of her own money—and Deval Patrick won the election. Of course, other times that kind of personal investment pays off: in 2002, Mitt Romney self funded his gubernatorial campaign to the tune of $6.3 million and won the election.

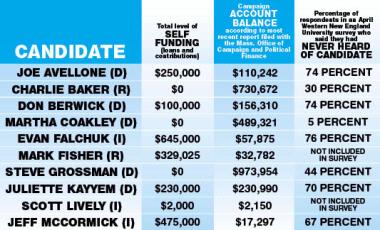

As the accompanying chart shows, in this year’s gubernatorial race, the candidates with the best polling numbers—Republican Charlie Baker, making his second run for the governor’s seat; Attorney General Martha Coakley and State Treasurer Steve Grossman, both Democrats—haven’t put a cent of their own money into the campaigns. Not incidentally, those three have been the most successful fundraisers by far, thanks, presumably, to the name recognition and connections they’ve established at this point in their political careers.

In contrast, lesser-known candidates are much more likely to use their own financial resources to try to jolt their campaigns and raise their profile with voters. So far, at least, that strategy isn’t necessarily paying off: for example, the candidate who’s done the most self funding of his campaign—Independent Evan Falchuk, who, as of the end of March, had donated $645,000 to himself—was unknown to 76 percent of respondents in a Western New England University Polling Institute poll released in April. Fellow Independent Jeff McCormick, the next-highest self funder, has put $475,000 into his campaign, through a combination of loans and contributions; 67 percent of respondents to that poll had never heard of him.

The three candidates with the highest name recognition? Coakley, Baker and Grossman, the only ones whose campaigns have not relied on self funding.

What does this vast level of self funding reveal about our electoral system?

“It’s not a coincidence that the U.S. Senate is made up of virtually all millionaires—multi-millionaires— and many of the governors across the country are also quite wealthy,” said Pam Wilmot, executive director of the good-government advocacy group Common Cause Massachusetts. “The amounts of money to run for office are incredibly high. … If you’re coming in new, the first thing the media looks at is your name recognition. If you don’t have any, you have to raise it by spending money.”

And it’s not just the media that evaluates candidates’ viability on their ease at filling a campaign war chest. “Funders have a harder time backing newcomers unless you have a vast appeal like a Robert Reich,” said Wilmot, referring to the former U.S. Labor Secretary who ran a populist, and ultimately unsuccessful, campaign to be the Democrats’ gubernatorial nominee in 2002. (And even Reich had to dip into his own resources, donating $200,000 to his campaign.)

Wealthy candidates, then, have a leg up, thanks to their ability to jump start their campaigns with their own money. But the benefits of wealth go beyond self funding, Wilmot noted: “Being able to self fund automatically gives you credibility. It also means you have rich friends that can help finance your campaign.” (The relatively low contribution cap in Massachusetts—individual donors are limited to $500 per campaign—forces candidates to broaden their fundraising efforts beyond a small circle of rich donors, although, Wilmot noted, “five hundred dollars is still a lot of money for most people in Massachusetts.”)

Voters, Wilmot said, are “ambivalent” about wealthy candidates’ ability to self finance their campaigns. “On the one hand, it is a terrible travesty that we have this wealth primary, and our officials typically come from a small percentage of our population” who “may have a difference set of experiences than those who come from less-wealthy backgrounds.” But on the other hand, she continued, self-funded candidates can appeal to voters who believe they’ll be independent of the demands of big campaign donors. “It means they’re not beholden to anybody,” Wilmot said.

“Money has become a stand-in for viability,” Wilmot continued. “That’s another reason why we support public financing of elections, with, obviously, some controls on who gets it and who doesn’t—so there’s some sort of measure other than money.”•