I was on a book tour around the publication of my fourth novel when I learned that I would be teaching an introductory course on writing fiction to undergraduates in the spring. Although I was in the midst of giving readings and talks in academic settings (as I have done for years), this was to be my first experience teaching a course. I have spent decades working with others around their writing: as a writing group member; as a consultant, coach and editor for individual writers; and, for the past four years, as Writer in Residence at our local public library. But I had never taught a college class.

The semester has been over less than two weeks now. I found teaching to be intense, demanding, productive and beautiful. One of the most the striking things about my first experience of teaching has been how central the practice of community was to every aspect of the course.

My friends who are teachers and writers were generous with suggestions, tools and advice for preparation. Being part of such a community is one of the biggest gifts of my impractical choice to make writing fiction a central activity of my life. I tried to emphasize this to my students: that the single most important thing you can do in support of your own work (besides actually writing it) is to be a good, respectful, active colleague to your peers. Responding to each other’s work, thinking through problems together, showing up to readings, trying to share access to opportunities with other writers and creating new ones when you can help shape your world into a place where both the work you want to write and the work you want to read can thrive.

This happens in concrete ways. The friend who had arranged my West Coast tour stayed up late piecing together a curriculum vitae for me out of my decades of scattered experience. I had a long conversation with another old friend who was putting me up after a reading she had organized, this one in New York City. Syllabi and guidelines for critiquing were shared over email. I got help with negotiating the institution. Great stories to teach from were painstakingly sent to me, one pdf at a time. There were conversations over lunch, over tea, in a car on the way to another reading in Boston. I want to say the names now, and give ways to find some of these writers and teachers, because the act of the reading their work expands the community to include the reader. Judith Frank. Kelly Link. Lynne Gerber. Lesléa Newman. Amity Gaige. Sarah Van Arsdale.

Then, fifteen students and I put the classroom chairs into a circle every week and strove to create a working community ourselves. We spent a few weeks doing writing exercises, reading some of those outstanding stories, and talking about elements of craft with the guidance of Annie Lamott and John Gardner. After that, we spent most of our time responding to student work. Every student wrote a letter to the writer of every story. The letter described the theme of the story; gave specific, concrete praise; raised questions and offered suggestions for revision. The conversation about the story followed this format as well, with the writer listening in silence until the end. The students were excellent readers of each other’s work, both rigorous and kind. The collective critique was always better than the written critique that I handed to each writer. Their writing got deeper, more embodied, more empathetic. The community of the workshop supported the individual writers in their tasks.

One reason this works, I think, is because writing itself is about creating connection. Here’s Annie Lamott on the question: why write?

Because of the spirit. Because of the heart. Writing and reading decrease our sense of isolation. They deepen and widen and expand our sense of life: they feed the soul. When writers make us shake our heads with the exactness of their prose and their truths, and even make us laugh about ourselves or life, our buoyancy is restored.

The week the course ended, I watched the Wim Wenders movie Wings of Desire, in which angels in overcoats move through Berlin, listening to people’s thoughts and trying to comfort them. At one point in the movie, an angel leans back, closes his eyes, and hears the great chorus of voices rising from a library full of books. At its best, getting to teach fiction writing felt a bit like standing quietly and intently next to a writer like an angel in the library. That does not happen in isolation, but as part of overlapping communities of teachers and students, writers and readers, developing the muscles to offer each other powerful – and I would say sacred – acts of attention.

Images:

Photo of Susan Stinson at Amherst College by Jeep Wheat

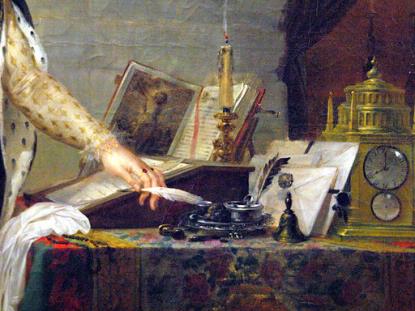

Philippe-Jacques van Brée, Marie Stuart, reine d’Écosse et prétendant au trône d’Angleterre, au moment où l’on vient la chercher pour aller à la mort, 19th c. Louvre; File from Wikimedia Commons