One hit from a Taser sends 50,000 volts of electricity coursing through the body. Oliver Rich, of Hatfield, sustained far more than that one night in 2010. Following a traffic stop in Greenfield, Rich was tased at least five times over the course of a few minutes.

The officers treated the weapons like “new toys,” he says.

In September of that year, Rich, now 36 and co-owner of Tea Guys in Whately, was driving near the Route 2 rotary in Greenfield when he saw two of his friends walking along the street around 8 p.m. He stopped his car and backed up along the Route 91 southbound ramp to give them a ride. A Greenfield officer in a cruiser spotted Rich’s move and pulled over. Officer Scott West told the friends to pile in Rich’s car and asked Rich for his license and registration. West, who is on military leave from the department and was unavailable for comment, discovered Rich’s license had expired.

From that point on, the situation escalated quickly.

In the Greenfield police incident report, West says he informed Rich of the expiration. In an interview with the Advocate, Rich says he disputed that charge and asked for his license back multiple times. In the incident report, West says he held onto Rich’s license because he was concerned Rich would drive away with it. In court documents, West says Rich “belligerently” continued to ask for his license back and had an “angry demeanor.” West asked Rich to get out of the Volkswagen he was driving and go to the back of the car. Once there, West told Rich he was under arrest and to put his hands behind his back-up. West says Rich refused to put his hands behind his back and continued to ask for his license. West radioed for back up and, in court documents, says he was beginning to think Rich had an “altered mental status.” West drew his Taser and continued to order Rich to put his hands behind his back. West claims Rich dared him to fire the weapon.

When his back-up arrived, West reholstered the Taser and the other officer attempted to physically place Rich under arrest, but according to the incident report, Rich refused and started flailing his arms. West was struck in the face, he says. At that point the officer stepped back, yelled a warning to his partner and fired the Taser.

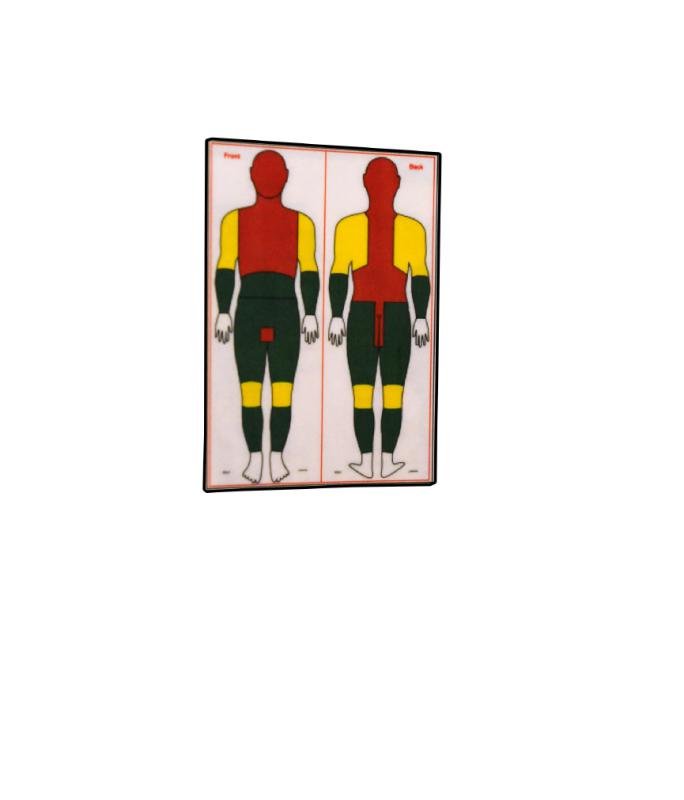

That’s not what Rich says happened. According to Rich, without warning, West held the Taser against his groin. As Rich saw three other police officers approach them, he says, West fired the stun gun into his groin. Rich says he was then tased as many as seven times by several officers in the groin, back of the arms and wrists.

In his report, West says he first tased Rich in the chest, but the darts didn’t stick, so he attempted to tase him again and again and again. According to the incident report, West tased Rich five times with various levels of success.

“I could’ve died,” Rich says.

Rich was arrested and charged with resisting arrest, assault and battery on a police officer, unlicensed operation of a motor vehicle and operating to endanger. The charges were later dropped. In September of 2013, Rich filed a lawsuit against the Greenfield Police Department in federal court claiming assault and battery and a civil rights violation. In December, Greenfield and Rich reached an out-of-court settlement — the city’s insurance company, Trdient Insurance Co., awarded Rich $87,500.

Greenfield Mayor William Martin told The Recorder last week that after the 2010 incident the city began looking closely at police procedures, that the suit was one of several lodged against the Greenfield Police Department at the same time. The complaints, according to Martin, had been “similar to the Rich one” and additionally involved “sexual harassment and other issues.”

Though the litigation was long and trying, Rich says he wanted people to know what happened to him.

“It almost destroyed my business and my family,” Rich says. “It’s been tough. It was really intense.”

Greenfield Police Chief Robert Haigh says he was not part of the department at the time of the incident and so declined to comment on the matter. He says Tasers are a good tool to have and there’s no way to prevent every issue.

“I think there is a risk for anything — you have to train the officers as best you can,” Haigh says.

According to Rich’s lawsuit, Greenfield revised its policy on Taser use the year after the 2010 encounter. The new policy specified, among other things, that Taser darts should only be fired “as a defensive tactic … in response to an assaultive person” and that Tasers should not be directed at the genital area.

About 10 years ago, Massachusetts legislators made it legal for police officers, with at least four hours of training to carry the controversial stun guns, which can temporarily immobilize suspects with a surge of electricity.Tasers, electronic weapons manufactured by Taser International, have been haled by police for their ability to avert greater injury. But they have killed 540 people in the U.S. since 2001, according to a 2013 report by Amnesty International.

Municipal departments across the state have made decisions based on liability, efficacy and finances whether to arm officers with the new equipment. Springfield is the latest department to opt for arming officers with Tasers. Police Lt. Trent Hufnagel says the city decided to go with Tasers to better protect officers and end stand-off situations more quickly and without fatalities. They are drafting a use-of-force policy that incorporates Tasers.

Some departments have embraced them, like Westfield, which was among the first department in Massachusetts to put Tasers on cops. Others keep their distance. In Northampton, for example, police have an arsenal of non-lethal weaponry.

There are troubling stories to be told, such as Rich’s, but there are also instances in which the weapons protect officers. It was this notion of protection that encouraged West Springfield to invest in Tasers about two years ago. West Springfield Police Chief Ron Campurciani says one night, in the winter of 2012, someone tried to steal a water truck. Two officers found the thief and tried to remove him from the vehicle. They almost got run over in the process.

“It just became this fight for life,” says Campurciani of that night.

“That was just crazy. I thought, ‘Somebody’s going to get killed.’ A Taser would have ended that in two seconds,” the chief says.

Campurciani says to prevent overuse, he doesn’t allow any of his officers to carry Tasers unless they are willing to be tased first. But not every department require cops to get blasted with 50,000 volts. According to state law, the training they must receive before carrying Tasers includes a review of device mechanics, the medical ramifications of using the weapons, a demonstration of how to use the tool and practice shooting it, and review of a state-approved use-of-force policy.

Having worked cases relating to Taser misuse, attorney Marissa Elkins who represented Rich during his legal battle with Greenfield, says she’s not sure that minimum police training requirements are enough. She says the devices have a lot of power and she’s seen officers running around with stun guns and inadequate training.

“There are departments in this area who have had unsuccessful implementations of Taser programs and that has led to abuse,” says Elkins, president of the Hampshire County Bar Association and an active member of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “If additional departments are taking them on I hope they will be mindful that these are devices that have caused significant pain and/or death.”

Westfield Police Department Captain Michael McCabe — who’s been a Westfield cop for 30 years — says Tasers have significantly reduced the number of injuries sustained by officers and the individuals they must contend with. McCabe, who is also a professor of law enforcement and community policing at Westfield State University, says a lot of people don’t realize how difficult it is to arrest someone. Many subjects, he says, don’t submit without some sort of struggle.

“It’s not all rainbows and unicorns,” he says.

McCabe says the Tasers themselves are not difficult to use, but the tricky part is calculating when their deployment is appropriate. Everyone’s perception of danger is different, he says.

Northampton Police Capt. Jody Kasper compares the continuum of force to two ladders standing side by side. The officer, she says, must always stay on the same rung of the ladder as the subject she is dealing with.

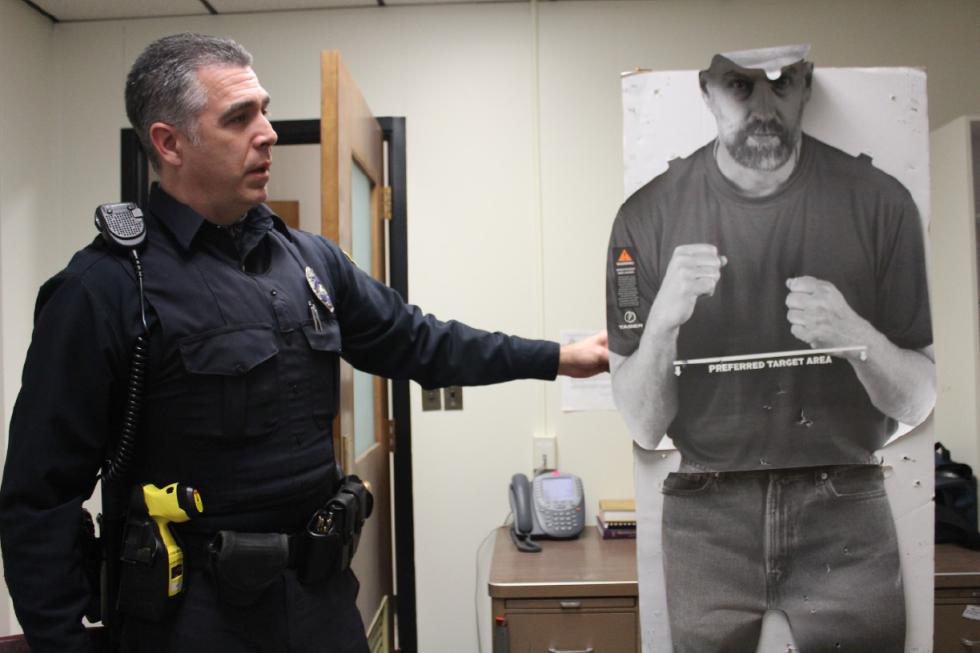

In general, says West Springfield’s Officer Joseph LaFrance, police shouldn’t tase someone unless that person is resisting and actively pulling away from being arrested. At that point an officer should deploy a “drive stun,” he says, a jolt that is delivered to a person when a Taser is held against them. The needle-like darts are not deployed. This move is meant to create pain, but not incapacitate a person. The next level of Taser response would be delivered to a person who is being assaultive and resistant. In this situation, LaFrance says an officer can use “dart mode” and fire the barbs at the target. This method is meant to incapacitate.

LaFrance says that with 20,000 service calls a year, the department has deployed Tasers six times in the 13 months they’ve had them.

Tasers themselves don’t kill people, Capt. McCabe says, but they can exacerbate existing medical conditions, resulting in fatalities. All in all, he says Tasers spare more harm than they cause and there’s only so much that officers can do when a subject becomes unruly.

“You’d hate like heck for it to happen,” McCabe says, referencing Taser-related fatalities. “But sometimes it happens.”

Northampton Police Chief Russell Sienkiewicz says Tasers just don’t make sene for his department. They’re too expensive at $2,000 or more each, there’s a lot of risk and the other non-lethal weapons the department has, he says, are equivalent in efficacy.

“When you look at the totality of the advantages versus the shortcomings, it hasn’t seemed worth the investment,” Sienkiewicz says.

Department Detective Sgt. Victor Caputo, defensive tactic instructor, and Kasper say their continuum of force does not include Tasers. Instead, officers in Northampton deploy pepper spray, batons, pepperball guns, and 40mm less-lethal launchers, which fire foam baton rounds. Caputo and Kasper say officers often resort to pepper spray and many have grown accustomed to being exposed to it themselves as the spray wafts around.

“We get sprayed a lot,” Kasper says.

Sienkiewicz says many of the resistant individuals Northampton officers deal with suffer from mental and emotional disorders, so he requires officers to receive mental health training from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. The training, he says, enables officers to deal with sensitive populations using as little force as possible.

“That’s a big piece of the puzzle,” he says.

LaFrance, West Springfield’s training officer, says the department uses Tasers as deterrents more than weapons. The Tasers’ bright yellow exterior, contrasting against officers’ dark uniforms, is enough to catch attention. LaFrance says people fear the pointed Taser darts enough to take a step back, especially when the weapon is unholstered.

“We don’t want to have to use them but we want people to know that we have them,” LaFrance says.

Campurciani says that whenever officers have to tussle with a subject, it never looks good and often results in injury. He references the many feather-ruffling Internet videos of cops making arrests, saying that Tasers can enable officers to avoid going hand-to-hand. At one point, he had 16 officers out at one time for injuries sustained on-duty — concussions, blown knees and elbows. Not only is that bad for the officers, he says, it’s bad for taxpayers who end up paying overtime to cover for officers out due to injury.

LaFrance says Tasers are catching on — that more departments are recognizing the benefits and that more career criminals are thinking before resisting.

“They’re building momentum,” LaFrance says. “People know what they are; they know what they do and they don’t want to tangle with it — the deterrent factor is enormous. Now that we’ve had them over a year, there’s no denying they’re saving injuries.”•

Amanda Drane can be contacted at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.