When I was a budding science fiction fan, I stepped into a con — a science fiction convention — for the first time. I was into SF, you know, for the books. The convention, it soon became clear, was about the spectacle of science fiction as delivered via other media. Somehow I came home with a pair of rubber Spock ears, some Ral Partha lead figurines, and a Klingon’s phone number. Once the crippling Mountain Dew hangover passed, I told myself I’d never do that again. And in fact, I haven’t gone near another such gathering since.

So when, a few years ago, a fantasy writer friend suggested I check out Readercon, an annual SFF (science fiction/fantasy) convention in Boston, visions of prosthetic foreheads danced in my mind. I wasn’t sure. My friend told me it wasn’t like that, that I would likely spot exactly zero Klingons. And, to be sure, the moniker “Readercon” sounds pretty sedate.

I warily agreed, and headed eastward. What greeted me wasn’t as sedate as the name suggested, but neither was it the alien-filled salad bar line of my nightmares. This year, I went again, for Readercon’s 26th iteration. The costume community, those who engage in the unsettling neologism “cosplay” by dressing up as the characters they admire, was represented, if only just, by one woman in a particularly dashing tophat. Other than that, it was only the sea of hipster eyeglasses that gave the gathering away as a science fiction convention.

What happens at Readercon is all about the books. No videos play, and no gaming appears on the schedule. What’s more, the many writers who visit Readercon are mostly inhabitants of New England. The Valley once again proves its mettle as a colony of scribblers by claiming a large number of those writers. This year — and it’s probable a Valley resident or two could go unnoticed on such an extensive list — local writers at Readercon included Mira Bartok, Jedediah Berry, John Crowley, Francesca Forrest, Gavin Grant, Kelly Link, Allen Steele, and, if you count Brimfield, Elizabeth Bear.

It all raises a couple of questions. Why bother, in a genre filled with dazzling visual spectacle and rabidly nerdy fans, trying to deny the apparent nature of the beast? Why have a science fiction convention that’s mostly a bunch of writers on panels discussing esoterica and tradecraft, you know, like a regular literary conference? Can that even work?

For Readercon’s current chair, Rachel Borman, the “why bother” part is straightforward. Readers of science fiction tend to be loyal fans of the genre, and the con presents an unusual opportunity for these serious readers: “To me, there’s the idea of a heightened sense of community,” Borman says. “We’re getting to know people who would otherwise just be names on the page. That’s front and center here.”

And indeed, Readercon includes kaffeeklatsches in which fans can have small-scale, relaxed conversation with writers they admire. It’s that kind of comfortable intimacy that distinguishes the experience. At Readercon, there are panel discussions in which writers hold forth in front of large audiences, but with a sprawling, four-day schedule, the event also puts readers and writers in such close proximity that you’re likely to find yourself accidentally having a bagel alongside the likes of John Crowley, a crafter of spectacular prose widely known for his unusual fantasy powerhouse of a novel Little, Big. Crowley says that for SFF writers, Readercon attendees provide a particularly broad-minded audience. He adds, “Genre is like the mafia. Everybody loves you until you want to get out. If I say that, I could find myself at the bottom of the river.” That mafia seems to mostly steer clear of Readercon.

Crowley has managed an interesting maneuver since the 1970s, when he first published. “At first,” he says, “I wrote science fiction because a genre novel was the easiest way to get in — you follow the rules, you get published.”

His reputation as a writer’s writer of SFF has remained in place since those days, however, he says, he hasn’t, in a certain light, written in the genre for years. He offers a recent work as an example, 2009’s The Four Freedoms. It’s almost a historical novel — it takes place primarily in a bomber factory in Oklahoma during World War II. Thing is, neither the factory nor the bomber they’re producing are real.

With such proclivities, he’s a good fit at Readercon. “[Readercon attendees] are much more generous than most SFF readers,” he says. “This is about books.”

Another Valley writer, Francesca Forrest, is the author of 2013’s unusual novel Pen Pal, about two people connected via a message in a bottle. One is a kid, and the other a prisoner suspended over a volcano on an island.

Forrest says, “Readercon is actually the only con I’ve ever been to, with one one-day exception — I went for an afternoon to Albacon in Albany, New York, once several years back.

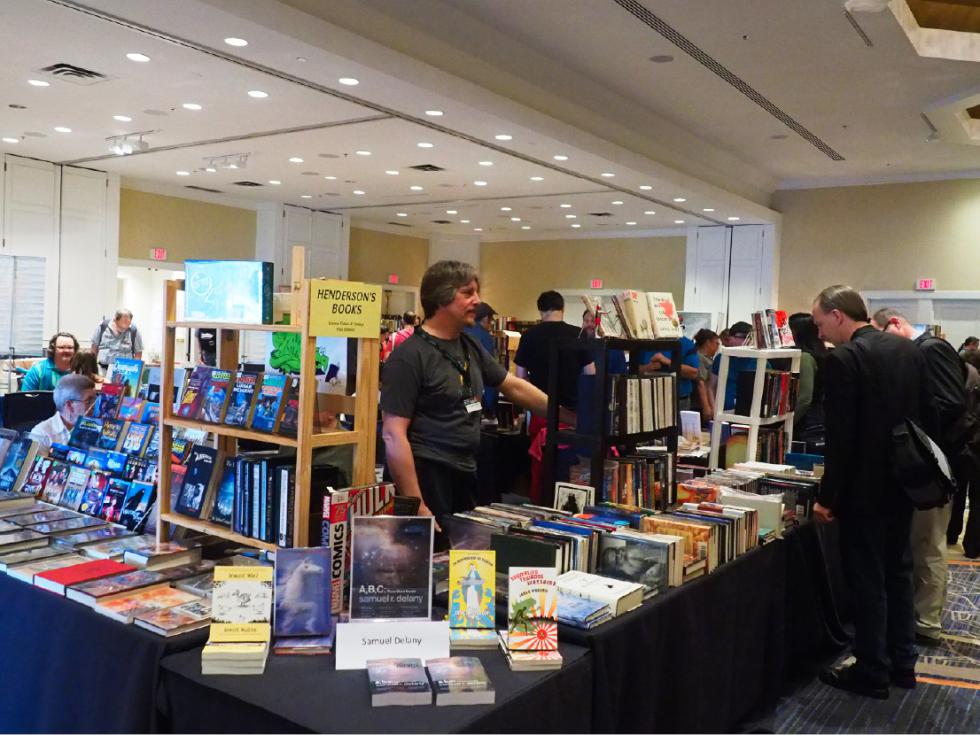

“People tell me that Readercon is unique in its intense, almost academic focus on books — as opposed to films or comics — and because it doesn’t have much cosplay or a place for selling art. Personally, I’d enjoy having art for sale, and cosplay would be fun, too. But the panels at Readercon are always interesting — even the ones on topics I don’t know much about.”

This year’s offerings included things like a discussion of books within books, in addition to less esoteric matters like discussions with editors and critics about the state of the genre.

Allen Steele, Valley-based writer of many a science fiction novel (perhaps most prominently the Coyote series) says he’s been attending all kinds of SF conventions since he was 15. For him, Readercon is set apart because its “emphasis is on the ideas being addressed by these forms. That’s very different, and very refreshing, from what usually goes on at the average SF convention these days.”

It should probably come as no surprise that our fertile literary region boasts such a rarefied version of a science fiction convention. Attending is a confidence booster if you’re a longtime fan of the genre, especially if you’re a fan who’s weary of standing up for the once-miniscule sliver of SFF that represents the best of the genre, and often the best of human imagination writ large. Maybe it’s illusion, but the sheer number of unusual — and exceptionally well-written and -imagined — SFF books on offer from the small presses who sell their wares at Readercon makes it easy to believe that sliver has finally grown to become the rule instead of the exception.

But that’s the high-flown version of things. Allen Steele points out what may be the real function of these gatherings aimed, at least in cliché, at a socially awkward fandom. “I call SF conventions ‘high IQ frat parties,’” Steele says. “They fulfill the same sort of function for those of us who don’t feel comfortable wearing a toga.”•

For more about Readercon, including details of next year’s event, visit Readercon.org.

Contact James Heflin at jheflin@valleyadvocate.com