About 500. That’s smaller than Smith College’s first-year class by 100 and it’s a tenth of the entering class at UMass.

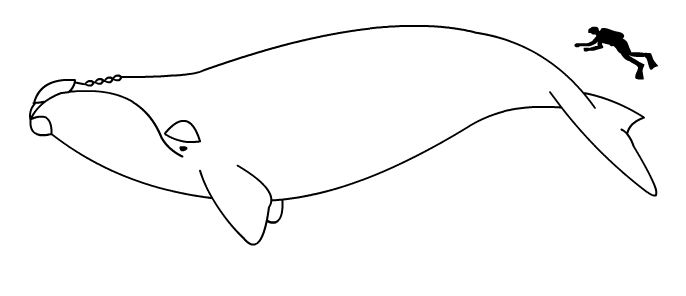

It’s also the number of right whales known to be alive in the entire world. These huge creatures — second in size only to the blue whale — are among the rarest whales on the planet.

And remarkably, about half their population has been spending each early spring just off the coast of Massachusetts in Cape Cod Bay. Arriving in March, they normally stay through April.

I visited Cape Cod this March over spring break. I didn’t go there expecting to see right whales. Although the Cape is ranked in the top 10 whale watching spots worldwide by the World Wildlife Fund, the whale-watch boats don’t run in early spring. Even if they had, the right whale population is so fragile that boats are forbidden to approach them, and focus instead on humpbacks, finbacks, and other species.

We found Provincetown sleepy and shut down, the beaches empty. This year’s strangely warm weather shifted to cold just in time for break. The air had a bite to it. Despite many hours of sunlight, from time to time thick gray clouds rolled abruptly over to dump their rain, shoving a parcel of cold wind ahead of them out to sea. But for me, the Cape’s desolation only increased its beauty, with its pitch pine barrens, its salt marshes, its broad dunes and beaches.

Only birdwatchers braved the beach in this season. On Race Point one morning, my husband Paul and I met an older gentleman on the dunes, his spotting scope trained on the water. Tall and refined, with white beard and hair, he was reserved, but my questions about birds soon warmed him. He took on a professorial fatherliness, ushering me to his scope to point out Iceland gulls, razorbills, and red-throated loons.

Then he told us where we could see right whales from shore. Not only that, he said, but a rare bird had turned up: a yellow-billed loon, the first ever documented in Massachusetts, not far from the whales near Race Point Lighthouse.

“I bet you’ll find birders who’ll share their spotting scopes,” he said.

We hurried off, eager.

We walked a long fire-road toward the lighthouse, over a dike that traverses a salt marsh. Glistening blue at high tide, the salt marsh’s waters had now retreated, and the marsh lay yellow-brown with reeds and rich with wildlife. Shorebirds had congregated and palm-sized snails slithered over the red mud.

At last we reached the long, sandy beach and bird-dotted waves. But we were too late. The whales follow the rip tide that escapes the bay before low tide, feeding on plankton that are sucked out to sea. We arrived just as the rip tide had run out of steam. We’d missed both whales and loon by 10 minutes.

Determined now to see them, we returned the next morning amid a frigid breeze. I felt a faint panic. What if the whales didn’t come today, and we’d missed our only chance? On the beach we found a crusty birdwatcher in his truck, spotting scope and camera thrust through his window. He beckoned to us.

“If you’re birders, come on over. If not, then go away!” he said.

We laughed and chatted with him. “If you want to see whales,” he announced, “then don’t move. They’ll be here with the tide.”

We huddled by his truck on the sand, protected from the wind. To our delight, the yellow-billed loon turned up.

Our companion gave me a good look at it through his scope, with its ladder-patterned back and its boat-shaped bill tinged with yellow.

And then the whales arrived.

The vapor gusted into the air, proving these were right whales by a blow jet split in two. Broad backs shone in dark curves through the waves. Big, curved tail flukes split the air. From time to time huge heads, speckled white with the lice that naturally parasitize right whales, broke the surface like floating rocks.

Our birding friend left. We stayed, transfixed by the honor of such a spectacle.

After an hour of watching, one massive whale came right to the shore’s edge, a mere 15 feet out. Paul saw it blow, but I did not. Still, I did see one side of its dark fluke rise from the waves as it rolled and vanished. And with that last salute, the whales were gone.

“It’s like it was saying goodbye to us,” said Paul.

Goodbye.

Right whales were hunted to near extinction during the whaling industry years because they’re large and have plentiful blubber and baleen, and moreover, when killed, they float. They’re also docile, and often swim near shore.

The whales have been protected from hunting since 1937, but their numbers have not bounced back, even after a near-total international moratorium on all commercial whaling in 1986.

Now, boat collisions and entanglement in fishing gear are the primary threats to right whales. Because right whales feed near the surface and swim slowly, they’re vulnerable to boat propellers. Recently, several viral videos on Youtube have shown boaters or divers rescuing whales from fishing nets by frantic efforts with a pocketknife. But for one lucky whale that finds a human to free it, many more drown, undiscovered. Spotting a right whale is “a last-of-the-dinosaurs kind of thing,” senior scientist Charles Mayo of Provincetown’s Center for Coastal Studies told the Boston Globe.

I felt joy to see the right whales’ handsome shining bodies, but also guilt. Who was I to be seeing these animals?

What right did I have to share such precious moments of existence with an animal so rare and so threatened? What had I done to earn this meeting — and will I no longer have the chance, 10 years from now?

They’re here, right here, on our own shores, silently calling us to help. They’re almost close enough to touch — but, to our shame, nearly too far away to reach.•

Naila Moreira is a writer and poet who often focuses on science, nature and the environment. She teaches science writing at Smith College and is the writer in residence at Forbes Library. She’s on Twitter @nailamoreira.