When Ray Sebold set out to build his environmentally-friendly dream house in Montague, he knew he would have to do it on the cheap.

“By no means are we rich,” Sebold says. “There’s no family money involved here. I personally have more skills than money.”

Seabold, 64, is a craftsman with a broad knowledge of building methods and standards, acquired through years of experience. His partner, Donna Francis, 61, is an environmental science professor. In 2003, they scraped together $54,500 and bought nearly three acres in Montague. They moved into an old trailer on the south side of their land, designing the house and saving money. In 2012, they broke ground on the project, with Sebold doing almost all of the construction himself. It was only in December of 2015 that they finally moved into their 1,300 square-foot home, and it’s still a work in progress.

Sebold and Francis say that taking their time enabled them to save money and consider every detail, taking care to make sure that the home was as energy efficient, comfortable, and non-toxic as possible. The result is a home as unique as it is practical.

“That’s one of the things that happens when you give yourself time,” Sebold says. “If you’re in a hurry, you’re just caught up with the details and you can’t think about anything else. I consider it a very old school way of doing things.”

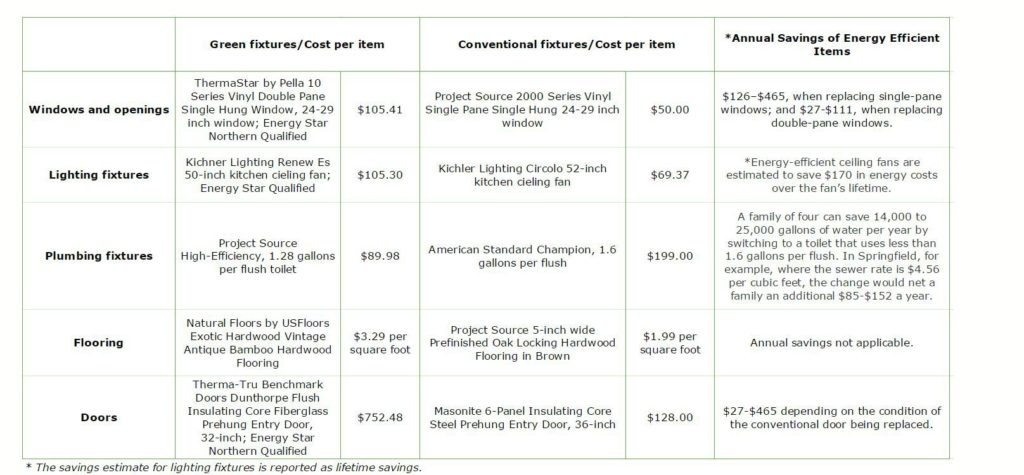

It’s common for home-builders to think that building a “green home” — a term Sebold says is akin to “natural food” in its dubiousness — is intangible on a budget due to the fact that more efficient windows and insulation materials are more expensive. Greener building materials do cost more up front, but the costs are offset in a number of ways. By focusing on sealing the house efficiently, using insulation materials far more efficient than those required under the building code, they were able to spend less on their heating system and at the same time decrease their heating costs. The entire house is heated with a $3,500, ultra-efficient mini split system. A heat recovery ventilation system moves air throughout the house with minimal heat loss.

In addition to the long-term savings on utilities, state and federal governments offer financial incentives in the form of tax credits, financing, and loans. Sebold and Francis were able to qualify for a loan through the Mass Solar Loan program, administered through the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources and the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center. Because they make less than $66,866 annually, they qualified for a 30 percent loan buyback.

Sebold and Francis also received a $7,000 credit for meeting the Mass Save tier three performance requirements, meaning that they’d demonstrated better than a 45 percent improvement over Massachusetts’ 2014 baseline standards and met Energy Star requirements. John Saveson, an energy rater at the Center for EcoTechnology, performed the energy audit.

“Ray’s house was one of the tightest I’ve ever tested,” he says.

The house received a HERS rating of 39, which means that it consumes roughly 50.8 percent of the energy a similar home would, according to CET’s Peggy MacLeod. Over the lifetime of the home, this amounts to serious savings.

Sebold and Francis’ house utilizes no on-site fossil fuels. In fact, he went so far as to replace his gas range with an electric after conducting a carbon monoxide test and feeling uncomfortable with the results. He’s still connected to the grid, but he’s meeting 100 percent of his energy needs with the newly-installed photovoltaic array on his roof.

According to the US Energy Information Administration, the average Massachusetts home used 615 kilowatt-hours of electricity per month in 2014, generating an average monthly bill of $106.94. That amounts to 7,380 kWh per year. The solar array on Sebold’s house is estimated to produce 4,500 kWh per year—more than enough to meet his greatly reduced energy needs. In fact, he and Francis are currently producing more electricity than they’re using and selling the surplus back to the grid for a net profit. At peak usage in January, Sebold’s house used the equivalent of $4 worth of electricity per day. At the current rate and including tax incentives, the system will have paid for itself in under six years.

It’s notable that nearly 84 percent of Massachusetts households still depend on fossil fuels for heating. Just over 14 percent depend on electricity from the grid. Just over nine percent of all electricity in the state is generated from renewable sources, meaning that about one and a quarter percent of electricity for heating in Massachusetts comes from renewable sources. The data is more nuanced still, with roughly 6 percent of the state’s total electricity coming from hydroelectric and biomass, while the remaining 3 percent is generated by wind and solar.

Sebold and Francis were also able to save money by creatively sourcing their construction materials, like when they found a free set of triple-pane windows they found on Craigslist, or salvaged redwood lumber from an old hot tub frame. There were times when they had to make the best of what they had, like when they ran short of slate tiling in the foyer and used local river stone and concrete to artistically fill in the gaps. The house is brimming with hidden gems that typify this kind of outside-the-box thinking, like small sentimental objects epoxied into knots in the hardwood floor. One contains a coin from a trip to Croatia, another two toy fish and locks of Sebold’s grandchildren’s hair.

“It’s a craftsman’s house,” he says. “It’s an artistic process in a lot of ways.”

Sebold and Francis moved into the house in December of 2015 and it’s still a work in progress. In place of a front porch — the next step, he says — is the trailer that he and Francis used to call home. It’s been detached from the plumbing and electric and is ready to be taken away. But this won’t be the end for the trailer. True to fashion, Sebold and Francis are donating it to Red Fire Farm down the road, where it will have new life as a break room for workers.

“You have to work intelligently and it can be done,” Sebold says. “I’ve been having the time of my life the last four years working on this.”•

Peter Vancini can be reached at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.