Dar Williams came to the Valley in 1992 to put down roots and start a career. Between then and when she left in 2000, she became a bonafide folk rocker, touring on a wave of good gigs that carried her to a breakout moment in 1996 with Mortal City, an LP that became an alt-classic for a whole generation of twenty-somethings waiting on a new millennium.

“I was working with coffeehouse volunteers, local radio stations, and promoters who were trying very hard, with limited resources, to bring music, poetry and life back into their downtowns,” Williams explained in a recent letter to her fans. Mortal City, a wistful and upbeat travelogue carried by a hopeful narrative, poetic lyrics, and a sleek full band comprised of friends, was “a statement of faith,” Williams says, “and now, 20 years later, I say it as a statement of fact.”

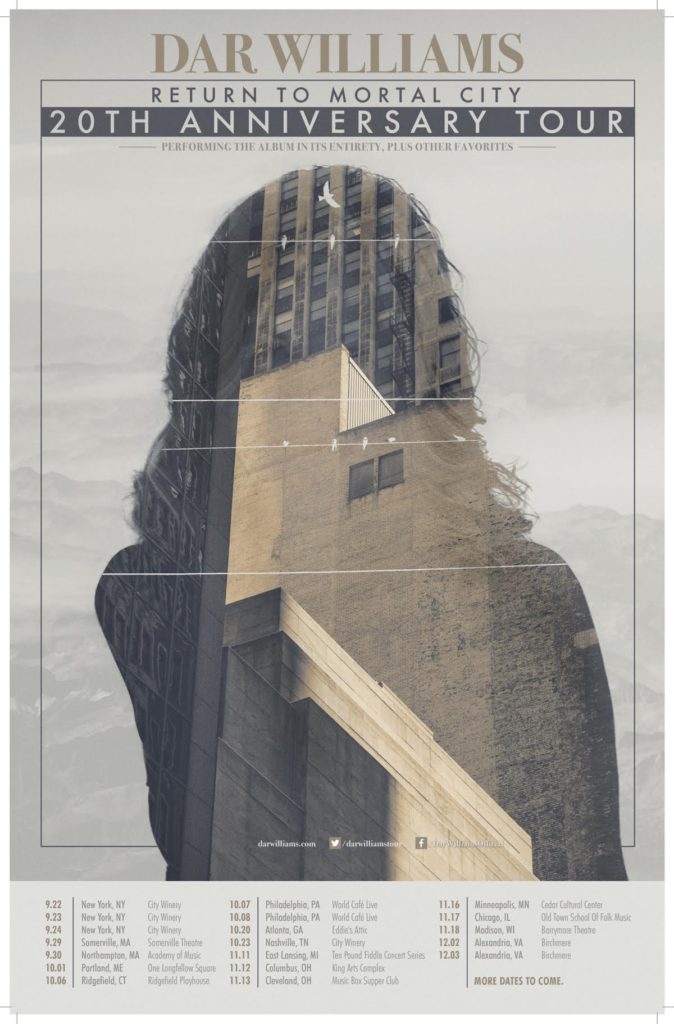

Dar Williams plays the Academy of Music on Friday, Sept. 30, joined by spoken-word artist and activist Alix Olson. The Advocate caught up with Williams by phone to talk about living locally, how America has evolved over the years, and about those first songs, written two decades ago. The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Hunter: We’re glad to see you back in Northampton. You spent a lot of the ’90s here. What do you remember most about that era?

Dar: I moved out from Boston, and on the first day I went on a walk in the Northampton community gardens, I saw a fox. I had never seen one before. I knew it was going to be a little wilder out here, and it was. The people were a little wilder, too. That’s what I needed — the mental freedom I found in the Valley. It was a very good time.

Dar: I moved out from Boston, and on the first day I went on a walk in the Northampton community gardens, I saw a fox. I had never seen one before. I knew it was going to be a little wilder out here, and it was. The people were a little wilder, too. That’s what I needed — the mental freedom I found in the Valley. It was a very good time.

At the time, I was getting mail-order vitamins. But I found people outside, in their own backyards, growing vegetables instead. I think the way that the Valley has embraced the local food economy has been really great for a sense of identity and neighborliness.

I try to always come back to perform. Recently, I was back to re-record one of the songs from Mortal City with the Valley band Kalliope Jones, and I got a chance to hang out with The Nields, which was awesome. I used to play the Bookmill [in Montague], and I remember writing lots of songs there, just staring at that waterfall — I think I wrote most of my first album there.

There’s always something that brings me back. It still feels like home.

Hunter: This is a 20-year anniversary tour for you to celebrate Mortal City. Why this album?

Dar: When my first album, The Honesty Room, did well, it was a great shock, and it was exciting. For Mortal City, which was the second one, I had to sit down and tell myself: okay, you only get lucky once.

Mortal City turned out to be the album that put me out into the world. It was a very special tour. People who came to see me open for Joan Baez are still coming to my concerts. Students who listened to me in college still get up and sing. These are the songs that brought me around this country, and into foreign ones. These are the songs that have kept me traveling.

Hunter: Is it true that you’ll be performing the album in its entirety for the first time?

Dar: Yes. I doubt I have ever performed every song from this album in one concert before.

Hunter: Have you changed much since Mortal City?

Dar: Everything has changed. A lot of these songs were influenced by traveling for the first time, because the country was new to me back then. Iowa, New York, L.A., Seattle — before, it was a whole new set of metaphors for me. Now, all these different places feel familiar, so in a way I think I’ve grown into the traveler that Mortal City turned me into. It is thanks to this album that I have this life.

Hunter: You’ve been all over the country. What do you see changing over the years?

Dar: Our country was reeling in the ’80s, more than I realized at the time. The country was rebounding from the proliferation of big box stores and the shutting down of plants, mines, and factories. But in the ’90s, people started to come back into their downtowns. In Mortal City, I still see glimmers of that.

Dar: Our country was reeling in the ’80s, more than I realized at the time. The country was rebounding from the proliferation of big box stores and the shutting down of plants, mines, and factories. But in the ’90s, people started to come back into their downtowns. In Mortal City, I still see glimmers of that.

Right now I see social evolution, by every measure. The LGBT movement, the local food movement, the environmental movement, legalizing marijuana … Even with mental health. I had clinical depression when I was 21, and someone saved my life. And I want to pay that forward. Awareness of the spectrum of mental frequencies — I think that is improving, too.

Being young in the ’90s, it was hard to see that happening in your lifetime. But we are setting our sights on healing social ills, really looking more deeply at what creates bigotry and racism.

Right now we have a lunatic [Republican candidate Donald Trump] running for president. He’s a snake oil salesman. It looks like a bad sign when people fall for bigotry and fear-based politics. You look at certain headlines, and it seems like we’re becoming more narrow.

But I’ve traveled everywhere. At a festival in Montana for a women’s work pants company, I saw a foundation raise money for women ranchers and farmers. People are recognizing that all of us are finding our way, and finding ways to be more inclusive of people who have traditionally been left out.

Hunter: If you could go back and talk to yourself 20 years ago, would you give yourself any advice on how to write or record Mortal City?

Dar: Everything about how we made that album was of its time. Offsite digital recording was new. We were ahead of the curve on that. Meanwhile, I was making new friends in the Valley, trying to connect myself and anchor myself there. I was very lucky. I was in the right place at the right time, surrounded by people that inspired me. So no, I wouldn’t change a thing.

Hunter: Are there particular songs or lyrics from that album that you feel are more potent or relevant now?

Dar: The song “The Ocean” has, I think, a sense of despair to it that I’ve seen even more up close now. I feel like I understand the despair of being young even more than back when I was younger.

On the other hand, there’s the line: “We are not lost in the mortal city.” That’s also more important to me now than it used to be. Democracy is fragile in its own, crucial way. At their best, people build cathedrals and beautiful public parks, and farms and CSAs and co-ops. And yet it’s just people.

We are the mortal city that creates all of this. So, do we try to build it strong because it’s fragile? Or has it always been strong? Whatever the answer, communities have flaws — but sustaining them is a beautiful thing.

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.