They form an army you might meet in a nightmare. Nearly one thousand glazed white figurines dressed in symbols of hatred — such as swastikas or the hooded robes of the infamous Ku Klux Klan — mass together and press close. With the installation of “The Hate Project” in Hampden Gallery, Steve Cole wields art as a double-edged sword, first to identify hate groups currently active across the United States and then to emphasize their surprising ubiquity. Hate groups are everywhere, in every state, and even here in western Massachusetts. By using art to bring hate groups close to home, Cole does not aim to celebrate a scary world. Instead, he hopes to increase awareness and help sustain an ongoing fight against intolerance.

Cole is quick to explain that the Southern Poverty Law Center has had a huge impact on his art project. The non-profit organization, founded in 1971, combats hate and discrimination through research, education, and litigation. Identifying hate groups and monitoring their activities, the SPLC has also compiled a graphic “Hate Map” [on their website, splcenter.org] every year since 1990, using icons to mark the geographic location of various types of hate groups around the country.

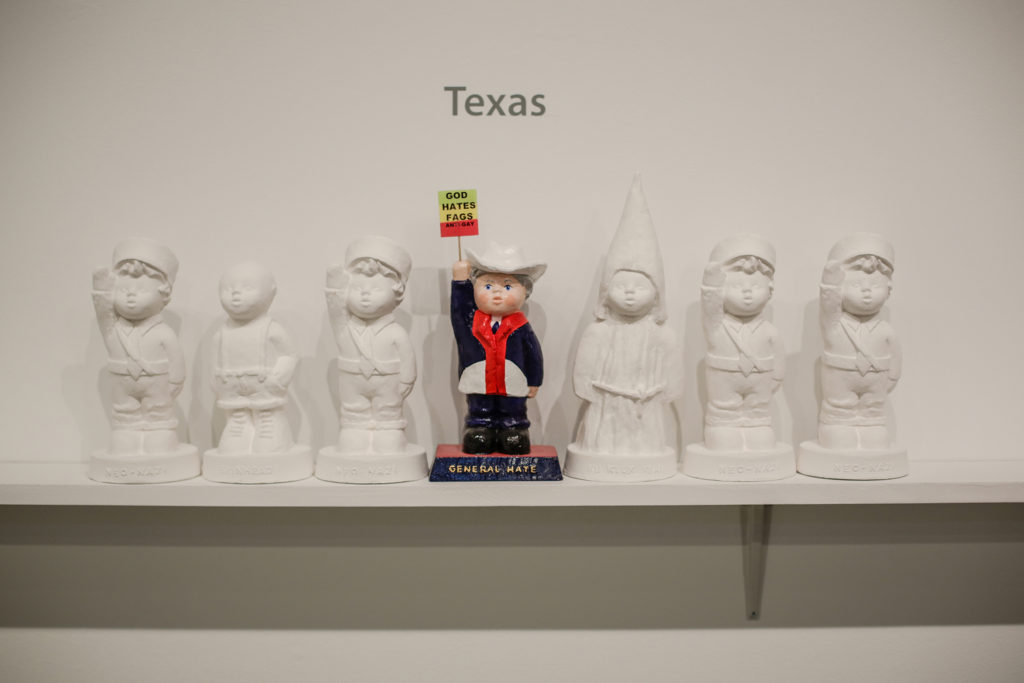

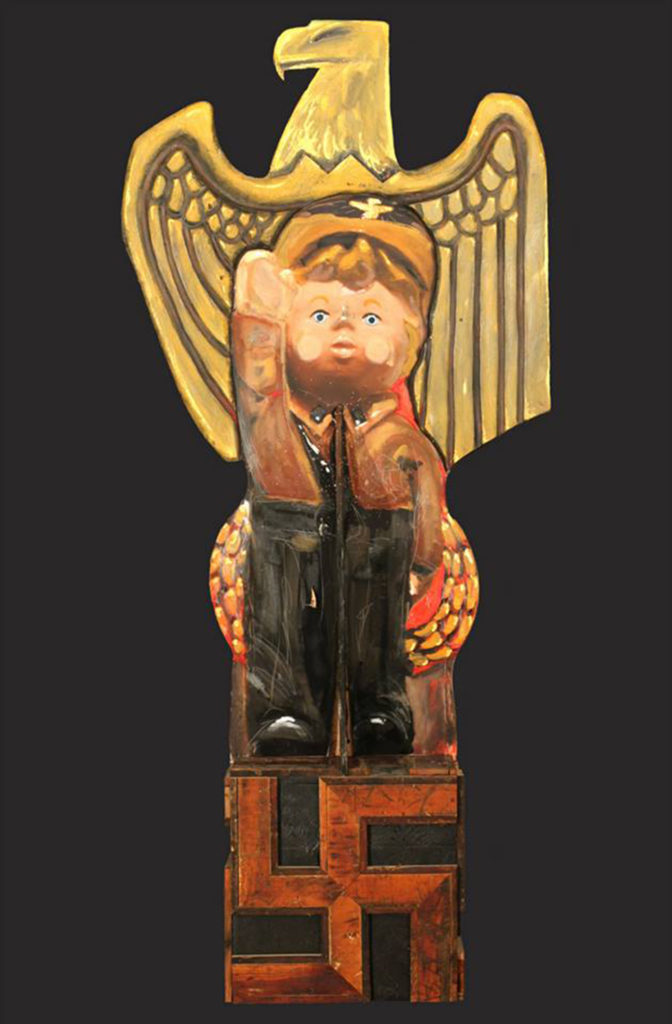

“So I thought I’d develop three-dimensional icons,” says Cole, “and it might be a powerful installation to map them out in a gallery, [showing] who they are, and also where they are in proximity to where people live.” He chose ten categories of hate groups and designed a figurine for each, symbolically representing the Ku Klux Klan, Skinheads, White Nationalists, Black Separatists, Neo-Nazis, Neo-Confederates, Racist Musicians, Christian Identity, General Hate, and Border Patrol (anti-immigration). Each figure stands nine to ten inches high, although the Klan figures, with peaked white hoods, tower at twelve inches tall.

“It took a lot of work to design the ten figures and then to cast nearly one thousand of them,” Coles says, with genial understatement. Well, the Klan was easy, he acknowledges, with the hood and robe. Neo-Nazi and Neo-Confederate groups also had obvious symbols in swastika and confederate flag. White Nationalism, Cole notes, is often couched in scholarly terms, so he created a figure with book in hand and finger raised, as if making a point — or delivering a lecture. Racist Musicians was a very small group, so Cole reached across categories to design an icon based on the granddaughters of Klan leader Thom Robb, Charity and Shelby Pendergraft, who formed a White Nationalist band. The figurine for General Hate — embracing anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant, and anti-LGBTQ groups — sports a cowboy hat to suggest Fred Phelps (1929-2014), pastor of the Westboro Baptist Church, notorious for picketing funerals of homosexuals and soldiers, and promoting violence under the slogan, “God hates fags.”

It’s disturbing imagery. Adding to the truly deeply creepy quality of the cast ceramic figurines is the way that they drape hate-filled symbols around chubby-cheeked faces of young children. (Imagine an infant with a diaper pin piercing his nose as well as his black leather diaper, and you conjure the incongruity.) Cole mentions his grandmother’s collection of Hummel figurines, in which each painted porcelain statuette broadly embodied an ideal or, some would say, stereotype. He recalls, in particular, one statuette of a young boy fishing. But he also references the young children that he saw at hate group rallies, “young kids brought along by their parents, learning to hate from an early age.”

Cole, a professor in the Art and Art History Department of Birmingham-Southern College, began “The Hate Project” in 2013, fifty years after the Ku Klux Klan’s bombing of the Sixteenth Street Church and other racial violence in Birmingham, Alabama. “Here we are, fifty years later, and we want to say everything has changed. Even the Supreme Court wants to say, ‘Racism’s gone’ but that’s not the case,” says Cole. “Hate groups are everywhere.”

And hate groups are here and now in Massachusetts. While the Ku Klux Klan sits close on Massachusetts’ borders with Vermont, New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, the SPLC’s current Hate Map tallies ten hate groups active within the Commonwealth. Statewide groups include the Nationalist Socialist Movement Massachusetts (Neo-Nazi) and the Aryan Strikeforce (Racist Skinhead). Malevolent Freedom (White Nationalist) has headquarters in Lowell; Boston is the base for three Black Separatist groups. And Springfield is home to the Nation of Islam (Black Separatist) and the virulently anti-LGBTQ Abiding Truth Ministries. “Typically, people are surprised that [hate groups] are so close by and that there are so many of them,” Cole acknowledges.

According to the SPLC’s research, there are fewer hate groups today than several years ago. But that decrease may be counter-balanced by hate-filled alt-right rhetoric that moved from fringe mutterings into mainstream conversation during the course of the presidential election.

“With all this new rhetoric, it’s much easier to be overtly racist,” points out Cole. With Donald Trump, he says, it became okay to be anti-Muslim, okay to be anti-immigrant. And with Mike Pence, it’s more acceptable to voice anti-LGBTQ bigotry.

Cole cites the example of Thom Robb, national director of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. In the recent past, Cole says, Robb played down overt racist statements to speak more in code and dog-whistles, and urged the respectability of suits and ties instead of the Klan’s traditional robes Now, the needle of acceptability has shifted dramatically, in part due to political campaign rhetoric and the rise of the alt-right. Cole says, “Overtly racist statements get a green light,” and Robb now can openly say things he would previously imply.

Despite that, Cole sees cause for optimism in art as well as the need for vigilance in society. “I hope that when people see “The Hate Project,” it will get some talking points going … For these issues of race and tolerance, if people refuse to sweep them under the rug, then we can work on it.

“It’s a threat,” he continues, “but we acknowledge it and work on it. We can’t allow hate groups to be empowered by a complacent society. Perhaps we can’t totally eradicate hate, but we can contain it.”

Steve Cole’s “The Hate Project” is exhibited at Hampden Gallery, located in the Southwest Residential Complex, UMass Amherst, through December 7.