COLUMBUS, Indiana — While Vice President Pence’s gubernatorial career earned national controversy, his hometown and closest friends vouch for his character. Columbus, Indiana, fits the image he presents: practical, family-oriented, and subject to change over the decades since his childhood there.

In the late-1970s, Pence and his friends were the picture of midwestern adolescence: basketball camp, drive-ins, and revved-up cars. But for friend Vic Thompson this was more youthful show than substance.

“We were probably the two worst players at the camp,” Thompson said. “[And] we always made fun of Michael because he was probably the worst driver in the world. Always more interested in telling you a story than keeping his eyes on the road.” He recalled a time Pence got them stuck with a bad shortcut in the dead of winter, “freezing our rears off.”

In 1976, Pence was an active Irish Catholic Democrat and soon-to-be Carter voter, whose grandfather had passed through Ellis Island only 50 years earlier. (In Congress, he often cited that grandfather when criticized for his softer immigration proposals, according to a 2006 New York Times profile.)

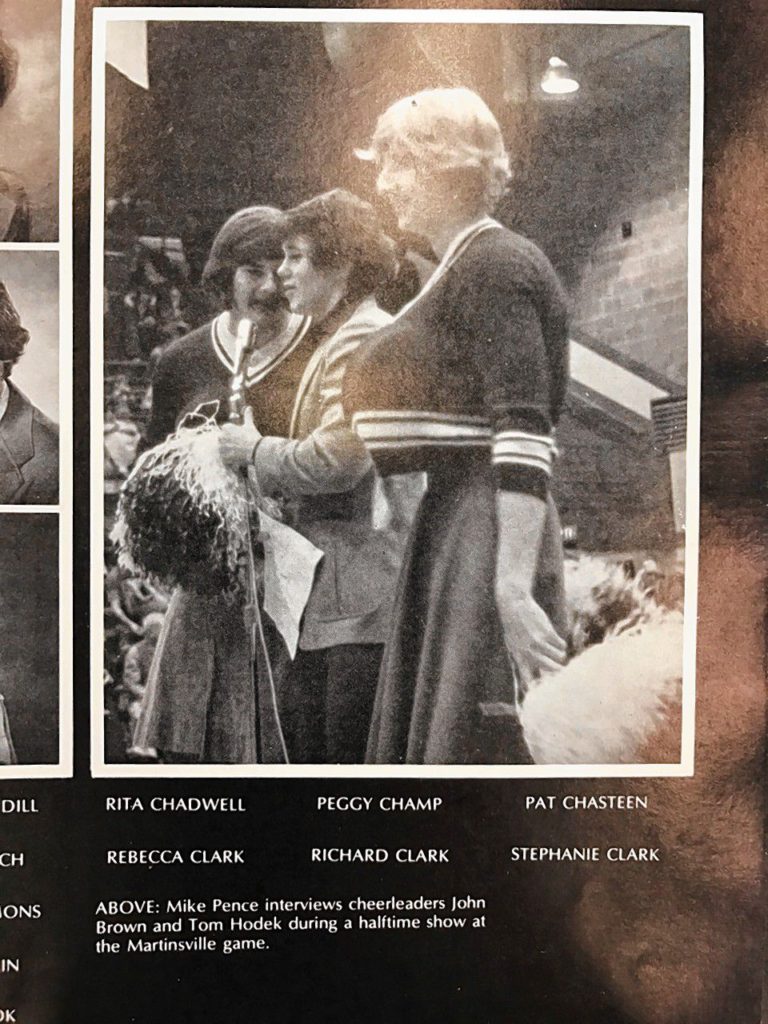

The class of ’77 had a reputation for achievement, sweeping sports contests and homecoming elections. Pence and his friends were its consummate showmen. His circle crossed through student government, speech, and even theatre; he emceed the school’s new talent show and its away-game halftime shows. Pence’s treatment of the constitution and the Bicentennial earned him Speaker of the Year. His speech team coach Debbie Shoultz declined to comment for this story.

The rest of Pence’s political history is by now well-documented. He soon left Columbus for Hanover College, and underwent a full political and religious conversion to conservatism. This shift would carry him from law school and two failed congressional campaigns to talk radio, the House of Representatives, the governor’s mansion, and later, the White House.

![]()

Today Columbus, a city of 46,000, has become its own sort of cosmopolitan. On a 70-degree weekend in February, couples speak Chinese and Hindi in a long line outside the ice cream parlor. Kids play in the massive indoor playground as parents hop next door for Bourbonfest.

Celia Watts, 44, has lived in the city her whole life. Her workplace, Viewpoint Books, has a sticker marked “LGBT Safe” on the front door, but she says the city has always been “typically very right-leaning.” History backs her up — in Pence’s senior year, the dean of girls “vetoed” a proposed Pabst Blue Ribbon hall poster by lighting it on fire. She said residents keep Midwestern mum, talking politics more online than in person.

The city is a mess of old and new, small-town and national, largely mediated through Cummins, an engine manufacturer that has long shaped the city in its image. To build its reputation for design, the company commissioned world-famous modernist architects to craft the cityscape. Residents write into the local newspaper to praise “radical agitators,” “former Mayor Brown and President Trump for their fight against fake news,” and “local pastors for speaking up against the [travel] ban,” all at once.

Jay Cole moved to Columbus 18 years ago from a struggling manufacturing town in Michigan. Cole said Columbus has grown its manufacturing while other towns haven’t. Besides modest decreases since 2015, the city has managed to build its manufacturing industry above pre-recession levels.

Jay Cole of Columbus, Indiana

Cole praised Pence’s governorship for its budget surplus, despite backlash Pence received for his more socially conservative actions.

“Everybody passes something that other people don’t agree with, that’s just what it is,” he said. “But all in all, he’s been a really good governor, and he’ll make a good vice president.”

In 2015, Pence’s signing of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act expanded protections for business owners to deny service based on religious beliefs. The law drew fire from both liberals and business conservatives nationwide, and was estimated to cost the state $60M in lost tourism business. Meanwhile, critics blamed the state’s HIV outbreak on his opposition to needle exchange programs.

Pence’s best friends look past these controversies to his character.

“Even though our politics might be slightly different, he’s very moral, very honest,” Thompson said. “Even if I don’t agree with the decisions he makes, I know they come from a good place inside of him.”

Pence’s friends and his hometown have gone separate ways. Some left town, others stayed behind, some stayed liberal, others conservative.

The year before Pence entered high school, the Columbus North yearbook seemed to forecast this change: “Consider the attitudes that shift with every person you meet. Conservative, liberal; what good are labels if you don’t believe today what you believed yesterday?”

Contact Steven Johnson at stetjohn@indiana.edu.