You’re a teenager in high school. You’ve been texting on your smartphone when you shouldn’t be or otherwise refusing to listen to your teacher. You think you’ll probably get berated, maybe detention, but never thought you’d be handcuffed and taken into police custody.

That’s the reality for some students who find themselves caught in the so-called “school-to-prison pipeline” – an acknowledgement of the increased rate of incarceration or juvenile detention among U.S. students.

An estimated 250,000 youth are tried, sentenced, or incarcerated as adults every year across the nation; most of whom are prosecuted in adult court and are charged with nonviolent offenses, according to a 2012 key facts sheet from Campaign for Youth Justice, a nonprofit advocacy group dedicated to ending the practice of allowing juveniles to be tried or convicted as adults.

Critics say the spike in student arrests has been fueled by district “zero tolerance” policies and the expanded presence of police in schools.

In Springfield, actions are being taken to stop the flow of students to prison, but not everyone thinks the efforts do enough. A neighborhood group is pushing for more clarity on what an arrestable student offense is as well as pushing to reduce the number of overall arrests. Meanwhile, Police Sgt. Clayton Roberson says officers are sometimes over-relied on to wrangle in unruly students and believes guidance counselors should be called in before an officer.

“Our goal is to work collaboratively and in the best interest of student safety and to that end we have established a clear and open line of communication between Springfield Public Schools and the Quebec Unit,” a statement from Springfield Public Schools responding to Roberson’s claims says. “If any such concerns were expressed by the unit or its members to the SPS administration, we would look into it right away.”

However, students who were interviewed by the Advocate seem to have a positive view of officers in their school and Superintendent of Schools Daniel Warwick said police officers are handpicked and trained for the job to avoid arresting students unless they are being violent, though not every arrest has involved violence.

Armando Olivares, 23, of Springfield, has lived the school to prison pipeline experience. He is now part of a volunteer organization, Neighbor to Neighbor, which is attempting to disrupt the flow of students to prison among other community-oriented goals.

When he was a 14-year-old attending Central High School in Springfield, Olivares said while his principal was giving him an order, Olivares just turned and walked away. He soon found himself handcuffed and “dragged out of the building” by a school police officer for the charge of disturbing a school assembly. He was put on a probationary period and was detained at a juvenile processing center for two days before being released.

The time at the processing center was disillusioning for Olivares. He no longer saw school as something that could be a positive force in his life.

“After that, honestly, my life took a rough turn,” Olivares said. “I started hanging around with the wrong guys. I wasn’t taking school too seriously. I was looking at school in a negative manner; I was looking at police in a negative manner. I was certainly a lost teenager.”

Olivares, 23, speaking at a Springfield School Committee in early 2017 about the school to prison pipelines. Olivares was arrested in a Springfield high school at age 14.[/caption]

Olivares, 23, speaking at a Springfield School Committee in early 2017 about the school to prison pipelines. Olivares was arrested in a Springfield high school at age 14.[/caption]

Three years later, Olivares was arrested and charged with murder in the shooting death of 20-year-old Reality Shabazz Walker in the early morning hours of Nov. 30, 2010. Three other men were also charged with the murder.

“At the age of 17 I was charged with something shamefully horrific,” he said. “It took two and a half years to clear my name out of that case.”

Olivares was acquitted of the crime in May of 2013 when he was 19.

In Springfield the school district has been working to crack the school to prison pipeline. Superintendent of Schools Daniel Warwick told the Advocate there were 80 total arrests of students during the 2015-2016 school year. It’s a lot better than what the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found when they dug into the problem back in 2012.

The report, “Arrested Futures,” revealed school arrest data for three school districts: Boston, Springfield, and Worcester. In Springfield, there were a total of 251 students arrested during the 2007-2008 school year; 134 of those arrests were for misdemeanor public order offenses such as refusing to follow an order by a teacher or administrator in a verbally confrontational manner, according to the report. That number dropped the following school year to 210 total arrests, 110 for misdemeanor public order charges.

African-American and Hispanic students were also disproportionately arrested compared to white students, according to the ACLU study. During the 2009-2010 school year, Hispanics accounted for 55 percent of the student body and 65 percent of all arrests as well as half of public order arrests. African-Americans accounted for 23 percent of the student population while amounting to 29 percent of all arrests and 40 percent of public order arrests during that school year.

“Officers are highly trained in problem solving,” said Police Sgt. John Delaney, public information officer with the Springfield Police Department. “Arrest is their last resort. The officers are there to assist the teachers and staff at the high [and middle] schools in Springfield … They’re there for a reason and that’s school safety.”

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the school district and the Police Department created protocols for how the officers in the department’s Student Support Unit, aka The Quebec Team, interact with students.

“We’ve provided training to the Quebec Team — the school officers, but we’ve even reduced the number of school officers over the last few years as well,” Warwick said. “The arrests are so far down I continue to be perplexed about what the issue is there.”

A total of 21 police officers from the Quebec Team were stationed at 19 schools in the district in 2011, according to the ACLU report. Warwick said there are a total of 17 police officers serving at district schools at the high school and middle school levels as well as alternative schools, who all receive specialized training.

Neighbor to Neighbor members recognized the improvements in the schools, but contend that not enough has been done. The community organization wants to re-open the Memorandum of Understanding between the police and school department to find out what constitutes an arrestable offense for students.

“We’re just trying to make sure that we have a clear understanding of what is an arrestable offence within a school just so people can be clear about what they’re doing within school grounds — if they can get arrested; if not,” Olivares said.

“I’m sure there has been improvements; I know statistically there has been, but [the number of arrests] is too high in my opinion,” he said. “They shouldn’t be higher than larger cities. It doesn’t make much sense if you ask me.”

Boston Public Schools had an arrest rate of three students per 1,000 during the 2009 to 2010 school year, according to the ACLU study. Comparatively, that same school year Springfield’s arrest rate was 9 students per 1,000. Although the total number of arrests has dropped significantly in Springfield, the Advocate was unable to find any recent data comparing the arrest rates between Boston and Springfield schools.

Meanwhile, students at Central High School said the police presence is making them feel safe. Quasseen Vickson, an 18-year-old senior, said he’s only seen classmates taken into police custody for fighting.

Police officers “make me feel safe — I’ve never got in trouble with the police or anything,” he said.

The school-to-prison pipeline has been on the cultural radar since at least the early 2000s. Many attribute the emergence of the school-to-prison pipeline issue partially to zero tolerance policies — a strict enforcement of regulations and bans against undesirable behavior or possession of illegal or dangerous items. “Zero tolerance” spread across the U.S. following the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, according to a report published by the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) called, “Fact Sheet: How Bad Is the School-to-Prison Pipeline?”

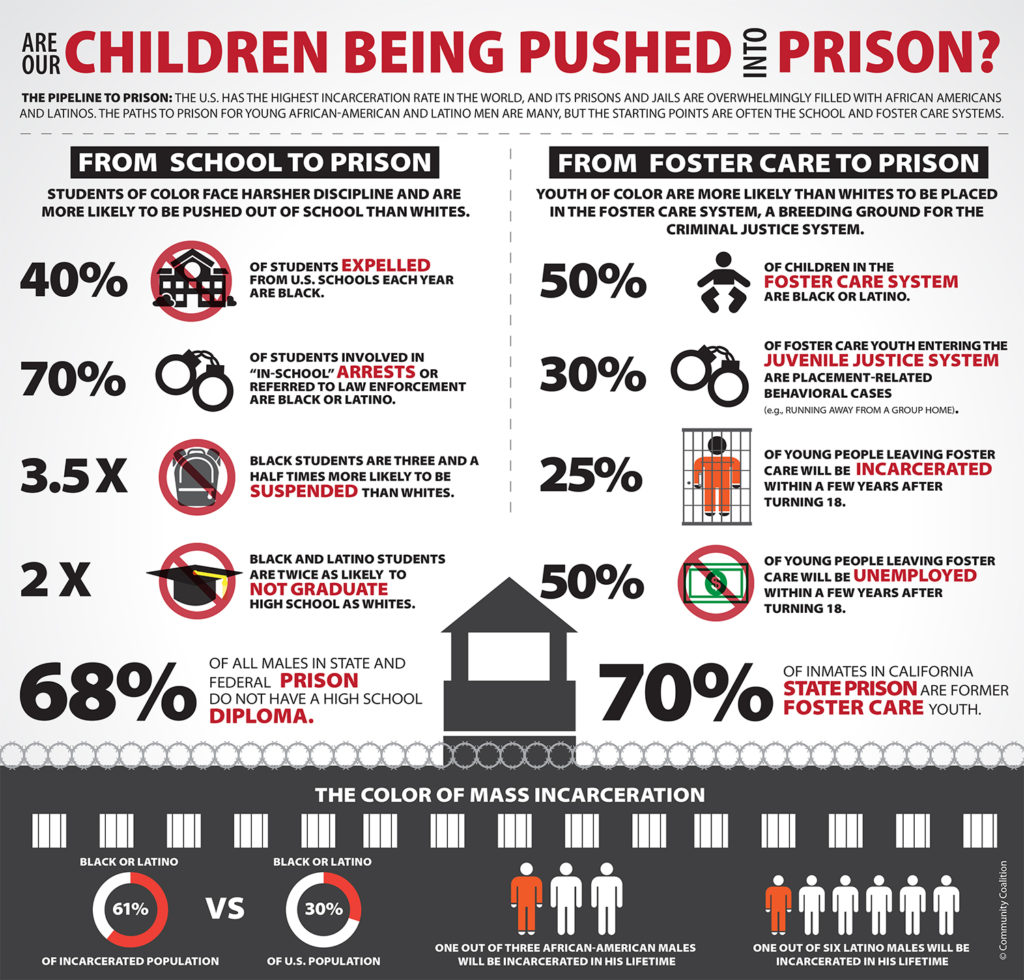

The main issue behind the school-to-prison pipeline stems with the long lasting damage to students who have been forced out of school for disruptive behavior or minor offenses. Those student might fall behind in their school work, which in some cases leads to them dropping out and then later committing crimes where they find themselves in a correctional institution. According to the report, 68 percent of all males in state and federal prisons do not have a high school diploma.

Ethnicity and race are part of the issue as well — 70 percent of students involved with in-school arrests on a national basis are Latino or African-American.

The cost of detaining a juvenile is also close to twice as much as an adult, Roberson said. There are 18 correctional facilities in Massachusetts that house at least 12,000 prisoners. The average cost of providing for one adult inmate on annual basis is about $46,000. One juvenile costs approximately $82,000 per year to detain.

Springfield has had officers in the schools for more than a decade — typically one officer is assigned at the middle school and two officers are stationed at the high school level. According to the fiscal year 2017 budget, the Safety & Security Department of Springfield Public Schools received $3.1 million for this year.

The goal for Springfield Public Schools is to allow students to build positive relationships with the 17 handpicked police officers who work in the district and to serve as protection for students and staff if a violent situation were ever to occur, Warwick said.

“That’s the way that we’re going to move our city forward … They are part of the Springfield Police Department, but we give them special training and they’re assigned to this duty, they’re not assigned to anything else,” Warwick said. “They really get to know the kids — it’s just not an officer at an off-duty assignment.”

Roberson, a veteran of the department for more than 30 years, said he believes the issue of students being arrested for behaving disorderly in classrooms stems from a lack of communication between school officials, teachers, and school officers.

“[School officers] are not running around wanting to make arrests … They can’t use us as a reactionary for, ‘Oh, this person is disturbing my class,’” he said.

However, he said he doesn’t blame school officials and thinks education on the part of school officials and officers is a key component to solving the problem.

One negative interaction between a police officer and a student could lead that student towards distrust with law enforcement, Roberson said.

Roberson said he’s never seen a copy of the MOU and believes most school officers haven’t either.

According to the MOU, which was signed on July 1, 2015, the minimum school resource officer training requirements include training in child and adolescent development and psychology, including juvenile law, school safety and security, tactical situations in school settings, conflict resolution, peer mediation, first aid and CPR, and training with regard to children with disabilities or other special needs.

One section of the MOU details distinguishing misconduct that should be handled by school officials from criminal offenses that are under the purview of law enforcement officials.

“[Springfield Support Unit] officers are responsible for responding to misdemeanor and felony offenses,” the MOU reads.[Springfield Public School’s] building-level administrators are responsible for responding to school discipline matters. The SSU officer shall immediately notify the SPS’s building-level administrator following an arrest of a student whether that arrest occurred on school property or off school property.”

When asked if he would be willing to engage in a discussion with Neighbor to Neighbor members, Superintendent Warwick replied, “If folks want to come in and talk about it I’d be more than happy to … I think you can always get better, so any ideas to improve we always welcome.”

However, Neighbor to Neighbor members like Olivares have a different view on the issue compared with Warwick.

Members of Neighbor to Neighbor have heard horror stories about Springfield students getting arrested over trivial matters or an overreaction by adults. Neighbor to Neighbor member Shaitia Spruell is a project assistant for Baystate Springfield Education Partnership. She runs an afterschool program for high school students through Baystate Health at Roger L. Putnam Vocational-Technical Academy. Through her work she’s heard students’ stories.

“I had one girl arrested for almost getting into a fight. I don’t think that was appropriate, but I’m also not her mother and I’m not a school admin,” Spruell said. “Other than that I haven’t had any other students of mine be arrested. But they all have a story about seeing students thrown on tables and arrested for something like painting their nails.”

But students at Central High School interviewed by The Advocate on their way home from school on March 21 said they feel pretty good about the police presence at school.

Kayvon Blake, a 17-year-old senior, said he’s only seen other students being taken into police custody for fighting or “being disrespectful” in middle school – never in high school.

Omar Martinez, a 15-year-old freshman, said he “never really sees officers talking with students,” and never feels unsafe around police officers.

After his two years behind bars, Olivares decided to help young people build a positive future for themselves.

“The fact that I could have spent the rest of my life in prison as a 17-year-old; witnessing first-hand how broken our criminal justice system is, and how I almost got lost in it – that inspired me to change,” he said.

“I made a plan upon my release. You need a plan upon leaving incarceration. If you don’t have a plan upon leaving a correctional facility you will help the recidivism rate. You will allow it to increase and be part of that statistic and I certainly wasn’t trying to be part of that statistic … I had this plan to come home and help as many young people as possible so they won’t have to go through half the things I went through,” Olivares said.

Olivares said he was part of a neighborhood gang before his imprisonment and found that it wasn’t hard to leave that life after his release.

“A lot of the guys respect my change,” he said. “We grew up. Life is looked at differently.”

After his release, he served as the director of community engagement with Project Coach, a Springfield youth program created at Smith College with a mission to help students excel academically and to get involved with their local community and was also involved with the Latino Chamber of Commerce. Today, he is an aspiring real estate agent and also works for a Boston-based marketing company called ASG.

“I was fortunate enough to be accepted back with open arms; to work with the youth enrichment program I was working with before incarceration called Project Coach,” Olivares said. “I had to get background checked and I was good to go because I had no pending case nor convictions. I credit Project Coach so much. They helped me so much before and after incarceration. They are and will forever be a family to me. I can also credit State Rep. Carlos Gonzalez. He gave me the opportunity … to be part of the Latino Chamber of Commerce. I learned so much while there. I also have to credit my parents. They never gave up on me.”

Contact Chris Goudreau at cgoudreau@valleyadvocate.com.