Jamey Summers is in a good mood for someone about to have surgery. Beside the 41-year-old Northampton resident, who sits on an exam chair, Dr. Kate Atkinson is going over the procedure with her staff — they will insert four small rods containing drugs to curb opioid dependence into the crook of Summers’ left arm. She’s never done it before.

“Ouch!” Summers exclaims as Atkinson uses a black marker on his arm to show where the rods will go, but his grimace quickly turns to a smile. “I’m kidding.”

Atkinson adds her own quips to the playful, pre-surgical atmosphere. “Do not drop these on the floor,” she says, ribbing her two clinical assistants as they pass her the implants. “They cost about $1,000 each.”

Summers is happy because after years of what he considers stigma from pharmacy staff during frequent pickups of his opioid addiction treatment medication, this procedure will allow him to receive his medication without having to go to the pharmacy.

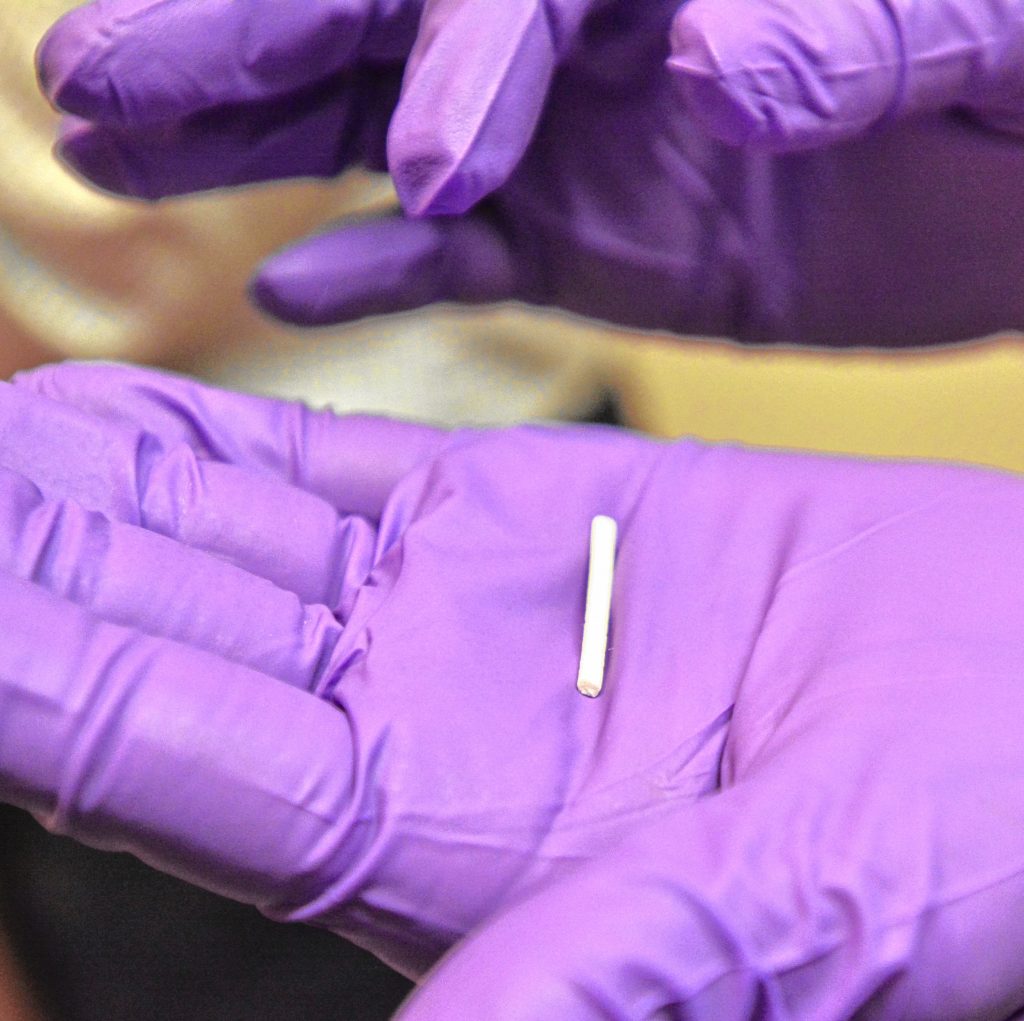

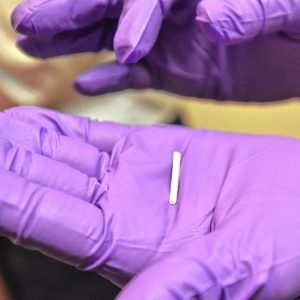

Dr. Kate Atkinson holds a buprenorphine implant, which delivers a low dose of opioid addiction treatment medicine to patients over the course of six months. Jerrey Roberts photo

The implants, called Probuphine, were approved by the FDA in 2016. The first of its kind, the implants contain the opioid dependence drug buprenorphine and release it in a slow, steady dose over the course of six months. They are designed to be used in patients who are already stable with low-to-moderate doses of buprenorphine, which is found in oral addiction treatment medications like Suboxone.

Opioid-related deaths have risen sharply in Massachusetts, with an estimated total of more than 2,100 in 2016. That’s more than triple the approximately 650 deaths in 2011 and a steady increase over the previous year, when about 1,800 people died, according to numbers from the state.

One of the tools Massachusetts has been using to curb abuse of prescribed opioids over the past several years is a prescription drug monitoring program — a computer database of all prescriptions, who is prescribing them, filling them, and taking them in the state. Control over that process has tightened in recent years.

As of last month, there were more than 290,000 people receiving Schedule II opioid prescriptions, the strongest legal kind. That’s about 4.3 percent of the state’s population, and a sharp decline from 2014, when 10.9 percent of the state’s population was being prescribed such medication.

The federal government’s drug classification system groups them into five categories, from illegal Schedule I drugs, like heroin, down to the least restrictive Schedule V drugs, like cough medicine. The system is actually pretty ridiculous, as less-addictive marijuana, LSD, and ecstasy are lumped in with heroin in Schedule I while harmful cocaine, highly addictive oxycodone, and deadly fentanyl are in the less restricted Schedule II category.

The state only reports prescription information on Schedule II drugs, so patients like Summers who use buprenorphine, a Schedule III drug, are not included in the data. But their prescriptions are tracked in the prescription monitoring program.

The success of the monitoring program can be seen in the number of patients who were marked as being individuals with activity of concern, which includes getting multiple prescriptions from different pharmacies in a short period of time. There were 250 people with activity of concern from April through June of 2017, a small fraction of the nearly 10,000 people with concerning activity during the full year of 2014, according to the data.

Dr. Kate Atkinson injects Jamey Summers with a local anesthetic to numb his arm before inserting four buprenorphine implants at her office in Amherst on Sept. 20, 2017. Jerrey Roberts photo

But for people like Summers, who depends on medication both for pain and to curb an opioid addiction, this aggressive monitoring program and the other regulations surrounding the use of prescription drugs, have made regular trips to the pharmacy unpleasant.

A few hours before his appointment, Summers spoke with me at his kitchen table.

“I’m a stable patient that has a great background and I go into the pharmacy and it’s always a problem getting this [prescription] filled,” he said. “They make up rules and they tell you some made up rules. You go up and research on the laws and they aren’t really the rules.”

Summers said he knows first-hand that opioids are dangerous, but wishes that stigma surrounding drugs shown to be dangerously addictive did not extend to drugs like buprenorphine, which helps people treat their addiction.

“It shouldn’t be grouped in with those medications, and we suffer because of that,” he said.

“They choose the most sensitive part of your body to put them in, but it’s okay,” Summers says in Atkinson’s office as he waits for his arm to numb. “I don’t care if it hurts as long as I don’t have to go to the pharmacy anymore.”

It takes longer than expected for Summers to lose feeling — so much that Atkinson asks physicians assistant Charles Milch to give him a second shot of local anesthetic.

“I wanted to learn how to do this so I went to Atlanta and learned all about it,” Atkinson says as we wait. “We just didn’t have anybody it seemed appropriate for at the time. All of a sudden, Jamey decided he really wanted it.”

The room is crowded, with Atkinson, Summers, Milch, and Atkinson’s two clinical assistants — Jordan Conrad and Will Johnson. On top of that are myself, photographer Jerrey Roberts, and a representative from Probuphine-owner Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, who is on hand to advise during the procedure, but does not want to be identified in this article.

Summers says he can’t feel his arm anymore, so Atkinson gets ready to begin.

At Summers’ kitchen table earlier in the day, he said he was prescribed Percocet for kidney stone pain in 2012 while living in Pittsburgh and then was further medicated again a short time later for a back injury.

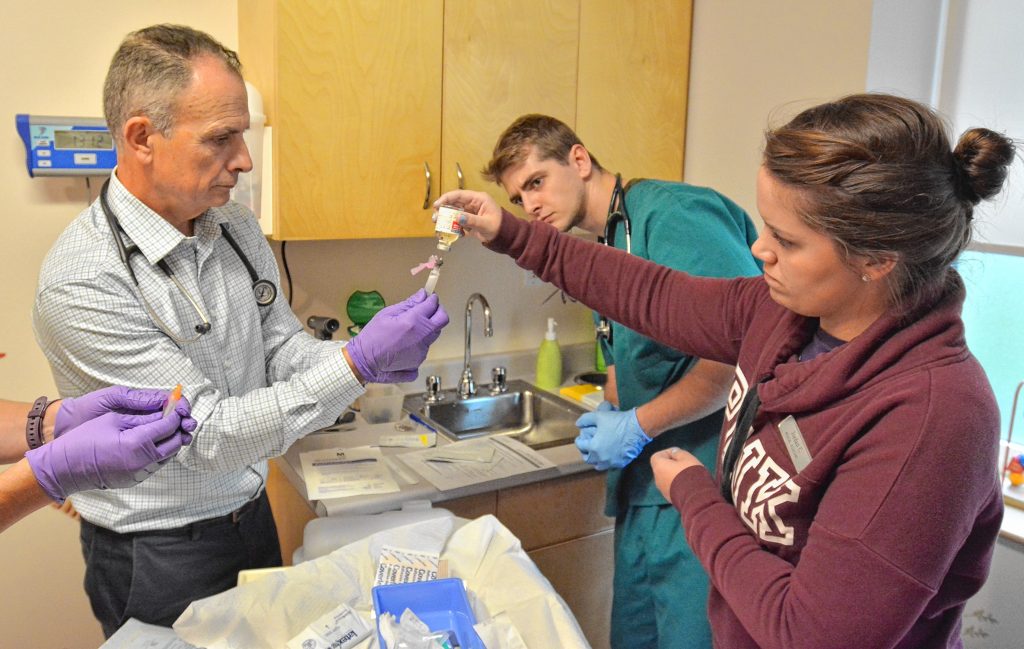

Charles Milch, left, who is a physicians assistant, prepares a syringe of a local anesthetic with the help of Jordan Conrad, a clinical assistant, in the office of Dr. Kate Atkinson in Amherst on Sept. 20, 2017. Will Johnson, who is also a clinical assistant, looks on. Jerrey Roberts photo

“What happens is you find out once you stop, you still need them, man,” he said. “You get sick, and you get low, and you get desperate, and me getting desperate scared the shit out of me.”

Summers never tried heroin, a drug many who get addicted to opioid pills use, but he has seen the toll heroin can cause. Two people in his life, a friend, and another friend’s mother, died due to heroin overdoses.

“This saved my life,” he said, pointing to his Suboxone medication.

Before he was treated, Summers said his cravings were like intense pangs of hunger.

“I was embarrassed to go and get seen,” he said. “I’m middle class and made good money and I hadn’t spent a day in a crack house or a slum, and here I am asking about this stuff.”

Summers described going into a clinic in Pittsburgh and paying $100 cash to a receptionist, then being taken through a shady process of getting what he was told was an MRI scan and then receiving a prescription. The doctor who ran the clinic was subsequently arrested, he said.

That was Summers’ wake-up call moment that he had to kick his habit.

“I can’t afford a criminal record. I don’t have one and I don’t want one and that’s that,” he said.

Summers, who is married with a young daughter, called his mother, who took him for his first addiction treatment appointment.

Since then he has tried many medications, with Suboxone being the best for him, but he called getting a medicated implant as “the holy grail.”

“It’s hands off, you’re getting your dose every day, you never forget to take it,” he said. “Kids can’t get into it; people can’t steal it; you can’t lose it. I think it’s the future of pain and addiction.”

When Summers and his family moved to Northampton two years ago, he said tighter Massachusetts restrictions and a stricter pharmacy culture around opioids made it difficult to fill his prescription, which scared him.

One instant he recalled from shortly after moving to Massachusetts was when he needed to travel and tried to pick up his prescription a day early. He was told in a curt manner that it couldn’t be done and was against the law. When he checked up with other pharmacists, he was told that he should have been allowed to pick up the medicine.

“She made up laws that didn’t exist,” he said of the pharmacist. “You can tell whenever someone is misinformed or when they are on a personal vendetta against a subject.”

That was not the case with Atkinson, he said.

“You have to trust your doctor and pharmacist or you’re going to be out there buying pills and heroin — you’re going to die,” he said. “I trust Doctor Kate with my life. She has been unbelievable.”

Atkinson slides a shoelace-shaped applicator under Summers’ skin and says she’s pleasantly surprised how smoothly the rod goes in.

One by one, she places the white rods, about an inch-and-a-half in length, into place through a small hole in the crook of Summers’ elbow. She says with a smile that she can feel the rods drop out of the applicator as they are put into place.

“We practiced on sides of pork, and you’re much better behaved,” she says to Summers.

She bandages him up — no stitches — and tells him to keep the bandage in place. Will it be sore, Summers asks.

“It could be sore,” Atkinson answers. “Just take some morphine — kidding!”

Pharmacist Paul Serio, reached at Serio’s Pharmacy in Northampton, said guidelines have gotten stricter around opioid medications, and as a result, those prescriptions do take longer to fill. There is a careful balance to strike when doling out addictive medication, he said.

Dr. Kate Atkinson inserts an applicator into the arm of Jamey Summers. Four lines made by a marker show where the buprenorphine implants will go. Jerrey Roberts photo

“Guidelines are in there for the safety of the consumer, but a patient shouldn’t feel that they are being blocked,” he said.

Recently, use of the state’s prescription drug monitoring program got tighter in that pharmacists now have to input prescription data within 24 hours of filling the prescription rather than in the past when it could be a few days or longer before the data was entered.

“It wasn’t very useful at that point because a person could visit several pharmacies before the system is updated,” he said.

The state also imposes restrictions including allowing for less opioid medication to be prescribed at once.

“If you go to a dentist, if you’re 18 or younger, you can’t get more than a three-day supply [of pain medication]; if you’re more than 18, no more than a seven-day supply,” he said.

Overall, Serio said he has seen benefits from the state’s actions and doctors switching to drugs like Suboxone for patients rather than stronger opioids.

“It’s for [patients’] benefit that there are steps in place to get ahead of the opioid epidemic,” he said. “That class of drugs are available and should be used where appropriate, but we need to monitor their distribution closer.”

State Rep. Peter Kocot, (D-Northampton), is the House Chair of the Joint Committee on Health Care Financing. He said Probuphine implants are an exciting direction for opioid treatment.

“You don’t have to take a daily pill and it can’t be diverted easily,” he said. “That is the problem with Suboxone. Folks have been known to sell the pills.”

Regarding stigma experienced at pharmacies, he said he has not heard testimony from patients that this is something they have experienced, but said he would ask about that at future meetings with health care stakeholders.

Kocot said a panel of doctors he spoke with recently said the opioid crisis had its beginnings in doctors offices. Doctors who wanted to treat their patients’ pain prescribed medication that turned out to be highly addictive. At the same time, the medical community does not want to be too restrictive of people’s access to medication that they need.

“People were overprescribing and these doctors admitted it,” he said. “Has it gone the other way now? I think that the health care community is trying to find that middle ground.”

One thing Kocot is learning through his meetings is that opioid treatment is unlikely to be successful if treated the same as alcohol abuse with abstinence and 12-step programs. Research is showing that a good percentage of the addicted population needs opioid treatment medication to stay off the harder opioids, he said. That’s another reason to be excited by implant treatment, he said.

“I tend to be cutting edge; I like trying new things,” Atkinson says, speaking to me while sitting on the exam chair recently vacated by Summers. “This [Probuphine implant] felt like it would fit in as a good tool.”

Atkinson, who believes she is one of the only local doctors certified to perform the Probuphine implant, says it is good to have primary care doctors perform the implant surgery, because they know their patients’ full stories and can be good judges of how well they will do.

It’s been the same for prescribing oral opioid treatment medication.

“I’ve been watching Suboxone save lives literally,” Atkinson says. “A young woman whose life was a total disaster — she was shooting heroin, and had been in jail, and thrown out of her house — I worked with her using buprenorphine. Over years going to [Alcoholics Anonymous] and getting help, she got off of everything.”

Eventually that person was hired to a high-paid job, Atkinson says.

“Jamey wants people to know that there are normal people who have these issues,” Atkinson says. “He’s gotten treated badly at pharmacies and stuff. The stigma is really hard.”

She adds that she hears frequently from patients that they have a bad time going to the pharmacy to get opioid treatment medication — made to feel dirty or bad and being publicly shamed when there are other people around.

So what should the country do in response to the opioid crisis? Summers has a couple of ideas, including allowing pharmacies to dole out single doses of Suboxone when someone comes in with a false prescription, to keep them from seeking pills or heroin on the street, at least for that night.

He also believes in a single-payer system of payment.

“We’re political junkies in this house, if I can use the word ‘junky,’” he said. “We eat, sleep, and breathe politics here and, of course, health care for all.”

Atkinson agrees with single-payer, and added that there needs to be an increase in primary care physicians and medical homes where patients feel safe.

“Our country and our state is going in the other direction,” she said. “They are trying to replace us with urgent care places.”

Missing in that model are the relationships you form with your doctors and the support you can receive from medical professionals, she said.

“The way our current medical system is, it is harder and harder for me to pay my bills,” she said. “I get paid less every year.”

Getting on board with new treatments like Probuphine implants and surrounding herself with staff members who feel the same way about innovation helps fight the sense that forces are working against her.

“To feel like you’re always looking for ways to make health care better, that keeps me from burning out,” she said.

Dave Eisenstadter can be reached at deisen@valleyadvocate.com.