Even among artists, Joseph Beuys has often flown under the radar, someone known more for his enduring impact than his individual works. During my days in art school, Beuys was a name dropped conspicuously into conversations by those who wanted to make sure you knew that they had gone deeper than most. Warhol, Duchamp? Beginner stuff, they seemed to say. If you wanted to get to the richer veins of art history goodness, you should be looking at Beuys.

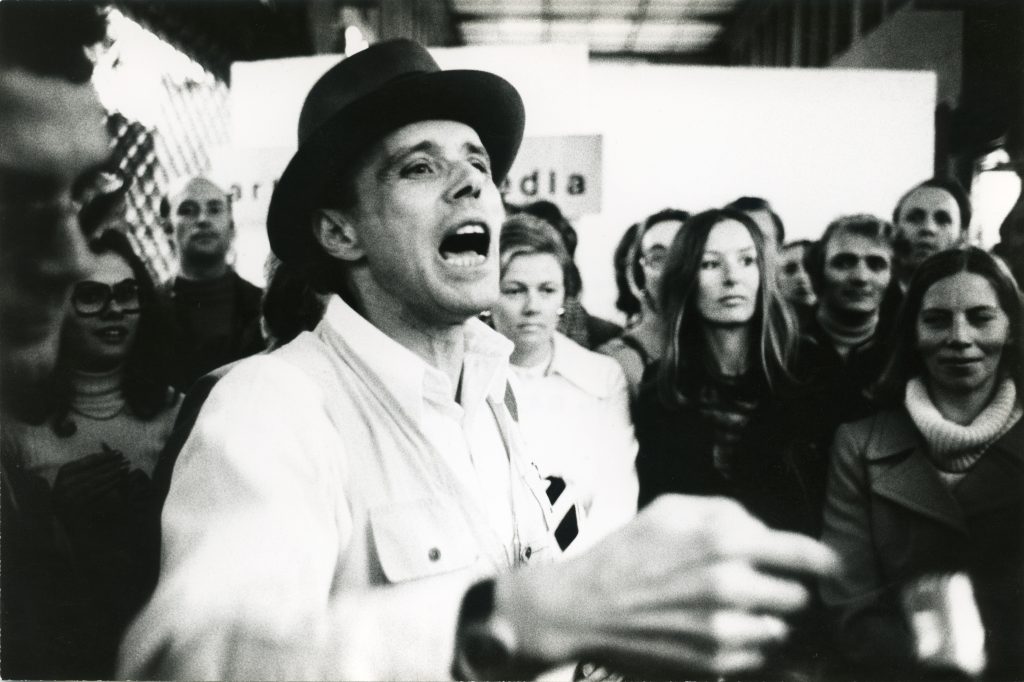

They may have been pretentious, but they weren’t wrong. The German artist, born in 1921 and a major force in the biggest changes in the art world of the 20th century, is indeed a deep well. In his trademark felt hat, Beuys went about his business looking a bit like a down-at-the-heels Bible salesman, but the work he did—a dizzying collection of performance pieces, drawings, sculptures, and more—was anything but traditional.

This week, director Andres Veiel’s film about the artist comes to Amherst Cinema in a Sunday morning screening as part of the theater’s New Films From Germany series. Simply titled “Beuys,” the film is not a documentary in the traditional sense; while there are some short interviews with contemporaries of the artist, the vast bulk of the film is archival material of the artist at work.

“Everyone is an artist,” declaimed Beuys, but he didn’t mean that we should all pick up a paintbrush. Instead, says Veiel, the phrase suggests that we all contribute to “a grander design” that is the collective work of all humankind. Like many artists of the time, Beuys was concerned with theories of art and politics, and how it all connected to the wider culture that too often felt disconnected from the art world—or worse, didn’t think that they should be connected.

Today, Beuys influence can still be felt in the boundary-pushing work of artists like Marina Abramovic. But it is also felt—with a connection that is perhaps even stronger, if less obvious—in the deepening political engagement of recent years, which has found creativity and civic involvement coming together in ways that would likely make Beuys, who once warned against giving over our political future to a group of elites, a happy man.

But if Veiel’s documentary is a welcome chronicle of Beuys’ work, there is a danger in approaching it without providing much context. Those unfamiliar with at least a bit of the artist may find that the freewheeling nature of the film is hard to follow, and that those works that are identified as some the last century’s most important are left frustratingly unexplored. Instead, those viewers are left to follow up on Beuys on their own time—and as much as the artist might be worth the effort, it may be asking too much to leave them wanting.

Also this week: another little movie called Star Wars: The Last Jedi hits the big screen on the 14th. You may have heard of it. The latest installment in the ongoing galactic saga reunites Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) and new heroine Rey (Daisy Ridley), last seen in an awkwardly tense introduction at the end of The Force Awakens, as the older Jedi begins to train Rey to use her newfound powers. For Star Wars fans—who after a long dry spell have seen three new films released in the last three years—December has become a wonderful time of year.

If you prefer your December fare to be a bit more traditional, area Cinemark Theaters have you covered there as well. This Sunday, they screen both a Bolshoi Ballet performance of The Nutcracker, and the holiday chestnut It’s a Wonderful Life. When the holiday shopping gets to be too much, duck in for a little getaway.

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com