Printmaker and Smith College art professor Dwight Pogue is retiring and he’s having quite a send off. His opus, if you will, is called Flowering Stars and is on view at The Smith College Museum of Art.

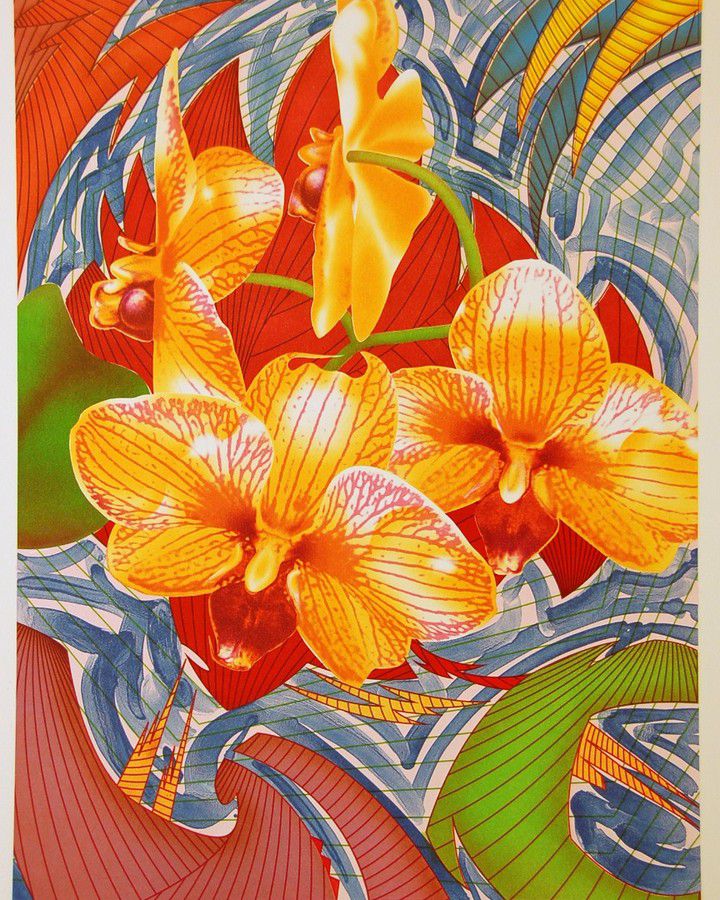

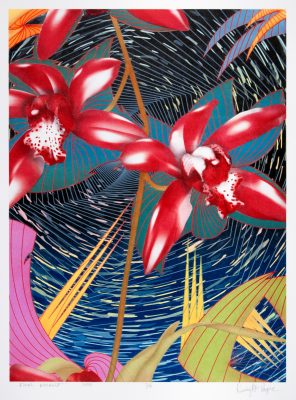

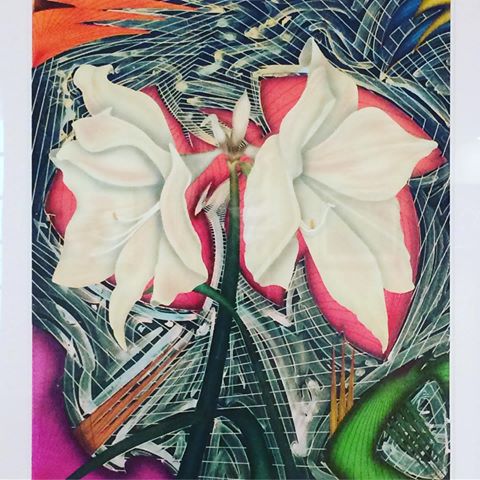

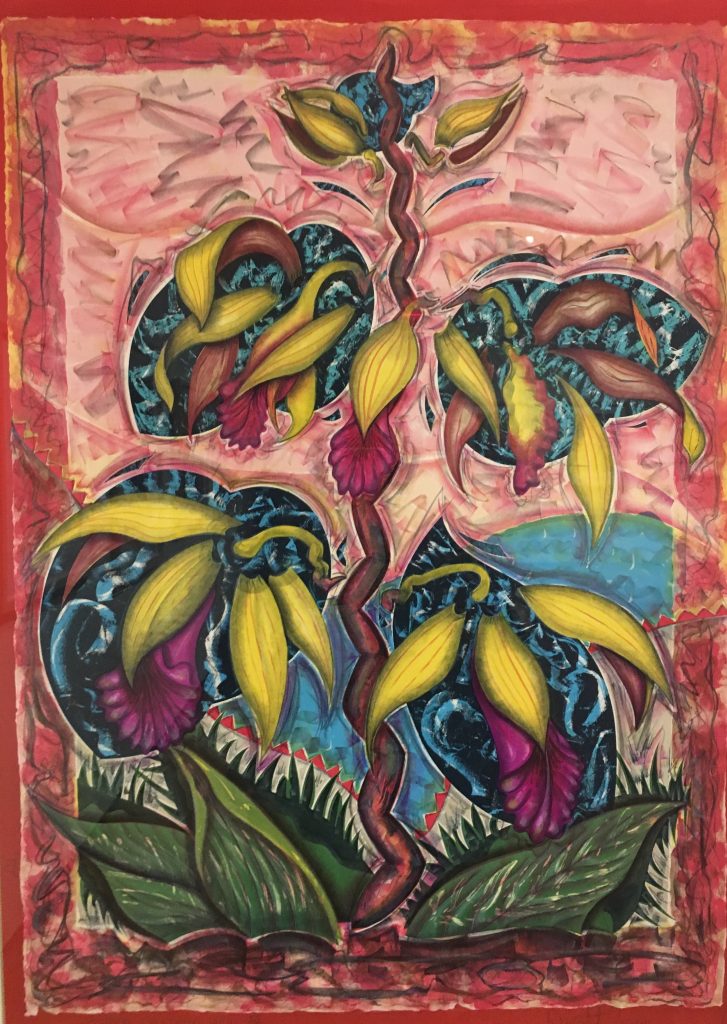

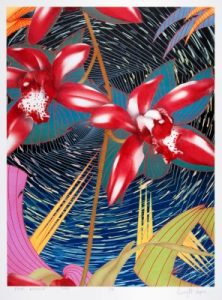

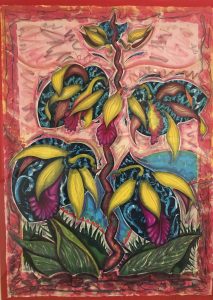

Pogue’s collection is a retrospective of his lithographs and screenprints over almost 40 years at Smith College, and it’s something to behold. ; and his changing styles are evident from the samples taken from his portfolio between the years 1984 – 2018.

Pogue’s work is on display on the second floor of the Museum of Art. It’s not a huge sampling, but it’s enough to appreciate the juxtaposition of subject continuity with the progression of skill.

You might call Pogue a quiet environmentalist who, through color, pattern, and intricacy of design, raises the profile of the humble flower to exciting new heights.

Of course flowers are anything but humble, and Pogue reminds us of a few very important facts: “Every fruit begins with a flower,” he says. Moreover, “flowers remove carbon dioxide and toxins in the air … [and] they feed honeybees that promulgate food crops.”

Flowers are often used as artists’ humdrum muses, but Pogue’s flowers pack a powerful punch, and he manages to make what could become mundane a delightful exploration of color and design.

Pogue’s retrospective allows for a wonderful glimpse into the artist’s changing styles and refinements. Refinement not only in craft but also in printing techniques themselves.

Pogue pinpoints a marked shift in his process in 1982 “when Smith College acquired a motorized flatbed offset proofing press.” Smith’s then high tech acquisition made it possible for him to “print layers and a range of textures in lithography.”

Lithography is based on the science of the resistance between oil and water. The artist draws their image with a greasy material on a lithographic stone. The stone is then chemically treated to etch the drawing into the stone.

The grease-based inked design is transferred to water dampened paper by running it through a press.

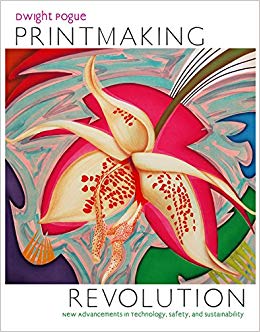

Here, too, Pogue has brought his environmentalist sensibilities; in 2012 his studio textbook was published. Printmaking Revolution: New Advancements in Technology, Safety, and Sustainability is a guide to using petroleum-free and biodegradable materials without sacrificing the subtle qualities of printing.

The evolution of Pogue’s printing technique in 1982 was shortly followed by his fascination with flowers; he began to “work in earnest on flower subjects” and would eventually come to use photographs he took of plants at Smith’s Lyman Plant house and other botanical gardens as his inspiration.

His works between 2010 and the present are gorgeously crisp and nuanced, whereas his earlier works are more jagged and reminiscent of the globalization of art and the Keith Haring-esque lines of the 80s and 90s.

Regardless of the decade, Pogue’s works are brilliant and graphic, dynamic and compelling. He manages a perfect mixture of abstraction and realism by balancing chaotic and vibrant backdrops with his beautifully detailed floral studies.

His abstract backgrounds are destabilizing, but Pogue is a master at countering the effect by striking the perfect compositional balance. There is no unevenness or lopsidedness.

His love affair with flowers is endearing and intriguing, and the titles of his prints flirt with the dangerous and/or romantic. It seems as though he personifies them with a moral rectitude and casts them as combatants of environmental villains.

Titles like ““Avoiding Atrocities” and “Break in the Battle” symbolize the weight he places upon the flower’s mission in the universe, and his dedication to their celebration is exhilarating.

Dwight Pogue’s Flowering Stars is on display until August 19. Smith College Museum of Art , 20 Elm Street at Bedford Terrace, Northampton.

Gina Beavers can be reached at Gbeavers@valleyadvocate.com