A mind is a terrible thing to waste, but it’s also a really hard thing to draw. It is, in a way, the ultimate intangible—a word meant to encompass the idea of ideas and thought processes. It’s therefore invisible and impossible to adequately describe, let alone depict.

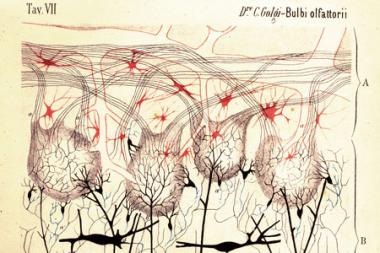

In light of that, the title of a new book by Carl Schoonover might sound far-fetched: Portraits of the Mind. And indeed, the author’s Jedi-esque first sentence is, “There is no portrait of the mind.” Schoonover’s book is, rather, a heavily illustrated history of attempts to image the brain, and early on at least, to divine how that most complex of organs relates to the notion of a mind.

In the foreword, Jonah Lehrer puts the kibosh on the very notion of mind as separate from the squishy thing that fills one’s skull: “…there is nothing else: This is all we are. The power of this beautiful book is to show us that the fleshy brain is more than enough, that it contains the multitudes and the machinery necessary to explain the wonder of our existence.”

Lehrer’s opinion notwithstanding, Schoonover elucidates a fascinating history, and makes it clear that he’s exploring a history not of simple brain examination and depiction, but of the techniques and tools meant to illuminate the search for connection between brain and mind. He includes the words of experts to explain the imagery and its context, and weaves a fascinating web in the process. The heart (so to speak) of the book is the collection of images.

Portraits of the Mind can be taken in very different ways. As a coffee table book for casual perusing, it’s absorbing—the images are astounding, from the early, crude renderings of ill-informed ideas about the circulation of animal spirits and various fluids and essences, to later works of Renaissance anatomists and recent images that are far removed from the expectations of how a brain, a neuron or a synapse might really look. As history, it’s in-depth enough to be informative, plainspoken enough to be an engaging read.

The mysteries alluded to in the beginning don’t often resurface—the scientists share details of their difficult quest to image a hard-to-access organ whose important processes take place at tiny scale, but over a relatively immense geography. Being scientists, they don’t tend to ruminate in print on matters philosophical or aesthetic. The images, a colorful parade of psychedelia and strange landscapes, create pleasures and questions that are well outside the bounds of science.

What does it mean, for instance, that the glowing aqua-blue picture of a neuron looks so much like something from a science fiction book cover from the ’70s? Are our imaginings of alien landscapes only helpless projections of what lies inside us?

At another level, it’s impossible not to feel a strange tension. A majority of these (often micro-scale) images are so utterly unfamiliar and unexpected that it’s tough to imagine how they might connect to the lived experience of thinking with one’s brain. Questions of soul and mind are here, of course, but these pages only provide endless proof that the brain is complicated beyond our current understanding, a wondrous landscape that complicates such mysteries rather than providing clear answers.

At times, the images border on the uncomfortable: a spiny neuron, it turns out, resembles some mute undersea monster whose beauty only lies in the extremity of its strange ugliness. Indeed, Portraits of the Mind makes a strong case that exploring the brain at the microscopic level means entering a world much like that of the deep ocean, a place nearby, yet inaccessible and full of the unexpected and terribly wondrous.

Science sometimes yields remarkable art, and, though perhaps the scientists who study the brain have no aesthetic purpose in view, the images here—if you take the time to fall under their spell—do more than art for art’s sake. Portraits of the Mind elucidates an interior world humanity has always wanted to understand, the very machinery of thought. That it does so while creating a rarefied beauty is a bonus.