In the city of Springfield, one out of every five residents speaks a language other than English at home, according to federal Census figures from 2003. Forty-one percent of them report that they do not speak English “very well.”

The majority of city residents who don’t speak English at home speak Spanish.

But that’s far from being the only other language spoken in the city. Forty-seven percent of that group speak a language other than Spanish—a reflection of the deep diversity in the city, which is home to immigrants from Russia, Vietnam, Latin America, Burundi, Somalia and other countries, as well as many Puerto Rican-born residents. Those figures are expected to increase when the results of the 2010 Census are released.

Springfield’s diversity is one of its strengths. But the diversity of its languages can also be one of the city’s biggest challenges. The public school system—where 57 percent of the students are Hispanic—struggles with how to work with children who come from non-English-speaking homes. In 2006, the U.S. Justice Department filed a voting rights lawsuit against the city for failing to adequately serve Spanish-speaking voters, prompting officials to hire more bilingual poll workers and provide translators, among other changes.

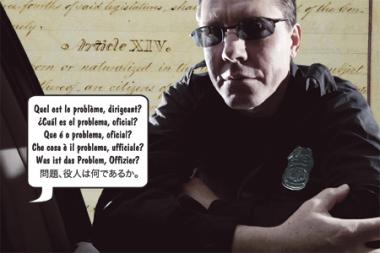

Now a group of city activists is calling on the Springfield Police Department to improve its services to residents who don’t speak English. The Pioneer Valley Project—a coalition of community, religious and labor groups—is advocating for a city ordinance that would establish strict protocols for how the SPD deals with non-English speakers, including bilingual interpreters and translated documents. The changes, they say, would ensure that the city is satisfying federal civil rights laws, and strengthen communication between police and residents in situations that can have life-or-death consequences.

Representatives from the SPD, meanwhile, say they take such concerns seriously, too—so seriously that there are already extensive, and adequate, systems in place for working with non-English speakers.

*

Last month, Pioneer Valley Project members came to a Springfield City Council meeting to make the case for a language-access ordinance.

In Springfield, long-time PVP Director Fred Rose told the Advocate, “there are a lot of folks who aren’t speaking English. And a lot of folks, in an emergency, who go back to what they know.”

PVP had been collecting information from members about non-English speakers’ experiences with the SPD. What they heard, according to Rose, were worrisome examples of what happens when the police and the public face language barriers: officers responding to a call and hearing an imbalanced, or incorrect, version of what had happened because only one of the parties could speak to them in English; people calling for help and not being able to communicate with dispatchers, or not even calling, because they don’t believe anyone there could help them.

Things could be improved dramatically, PVP contends, if the city were to follow the lead of a number of other cities around the country, including Hartford and New Haven, by adopting a language access ordinance. The group envisions a policy that would first assess language needs in the city, then set up a system to ensure that the public can get the police help they need, no matter what language they speak, through an interpretation system available both to callers contacting the department and officers on the street. PVP would also like to see the SPD appoint a staffer to oversee the language access program and establish a procedure for resolving grievances.

Such an ordinance, Rose said, would help the police as well as the public by ensuring that officers get as much information as possible as they go about their work.

It would also ensure that the SPD is complying with federal laws, including the 1964 Civil Rights Act, that guarantee equal protection to all people, whatever their language. Indeed, recipients of federal funding—including police departments—could lose that funding for failure to comply. In a 2006 article in Police Chief Magazine, Bharathi A. Venkatraman, an attorney with the U.S. Department of Justice, wrote, “In addition to private lawsuits, police departments that fail to account for the needs of non-English speakers are subject to investigative scrutiny by federal agencies. Most police departments receive federal financial assistance and must comply with federal civil rights laws as a condition of the assistance received.”

The PVP effort has the support of the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts. Bill Newman, director of the ACLU’s Western Mass. office, cites the equal-protection guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment. “Certainly, police protection is fundamental,” Newman told the Advocate. “The ordinance that we’re helping to develop really seeks to help realize that guarantee of equal protection.”

*

There are already provisions in place at the SPD to ensure that non-English speakers get that protection, say department members. When callers who need language translation call 911 for help, the call takers can access, with a push of a button, a statewide translation service that’s available 24 hours a day, said Sgt. Charles Scheehser, who runs the SPD’s dispatch center. The service has translators available in a wide variety languages, who speak to the caller and relay the information to the department dispatcher.

“It’s as easy as turning on a light switch,” Scheehser told the Advocate. The service, he added, is accessible whether the call comes from a land line or a cell phone.

Non-emergency lines at the department are not tied into the translation service, Scheehser said. But the SPD also has access to a toll-free translation line, which is used primarily during the booking process. Officers on the street who confront a language barrier can also access that service, he said.

But, Scheehser added, “From my first-hand knowledge of the street, it’s usually easier to look for help in the neighborhood,” by asking a neighbor or family member to help translate. “Most of the time if [language is] a problem, there’s someone there who can help.”

Sgt. John Delaney, a department spokesman from Commissioner William Fitchet’s office, said the SPD already has a number of procedures in place to address communication problems. Many officers, as well as dispatch staffers, he said, speak Spanish—the most common language among non-English speakers in Springfield. He also pointed to the 24-hour-a-day translation system available in the dispatch center.

While he understands the activists’ concerns, Delaney said, “I don’t see this as a glaring problem.” Breaking down language barriers has been a priority for Fitchet, Delaney said, noting that he and the commissioner have both met with PVP members to discuss their general concerns, as well as specific cases.

“We’re pretty proactive with that,” Delaney said. “The police department is kind of ahead of the curve.”

*

But PVP maintains that the system in place at the SPD is full of holes. When police responding to a call rely on neighbors or family members to translate, Rose says, they run the risk of getting bad information. Maybe the translator doesn’t know all the facts; maybe he is actually an aggressor who will use his language advantage to persuade police that there’s no problem, while a victim who can’t speak to the officers can’t contradict him. “They don’t know who to trust,” Rose said.

Sgt. Scheehser, of the dispatch department, says officers don’t overly rely on the information gained from informal, on-the-scene translators. “They’re only going to use it for preliminary anyway. They’re not going to base the whole investigation on the neighbor’s translation,” he said. Instead, Scheehser said, the officers will gather what facts they can at the scene, then bring the parties back to the station, where they can access the phone translation system.

But PVP sees problems with that translation system as well. Across the state, when a call is placed to 911 using a cell phone, it goes first to the state police, who then route it to the relevant local department; according to Rose, PVP has heard from its members of cases where such calls have not been able to access the translation service.

That shouldn’t be the case, according to Scheehser, who says the service is accessible for all 911 calls, regardless of what kind of phone they’re made from.

In addition, Rose said, his group has also heard of cases where an officer on the street has not been able to access the translation service, or needed to find a pay phone to access it. And, PVP members told the Advocate, they’ve talked to officers who’ve told them they didn’t even know the translation help existed.

“[The SPD’s] answer is, ‘There should never be a problem,'” Rose said. But PVP believes the system has dangerous flaws. “It’s partly training. It’s partly access through the internal system. There’s lots of holes in this,” he said. “We don’t know all the ins and outs of why these problems happen. We just know they happen. But it’s their job to figure it out. …

“I’m sympathetic with the police department—they’ve got a zillion things to deal with,” Rose added. But a stronger translation system, he said, would benefit officers as well as the public, by making their jobs easier and safer.

“This ordinance, as it will be drafted, is a clear first step— how to make translations, when necessary, more accessible, more readily available,” added Newman, of the ACLU. “Because what these stories [gathered by PVP] show is that there’s a system that exists, but it’s not really responsive.”

*

A language access ordinance, supporters say, could go a long way toward plugging up holes in the existing translation system, including designating a staffer with ultimate responsibility for how it’s working.

A number of other cities already have similar ordinances in place. In New York, where 25 percent of residents don’t speak English as their primary language, Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed an executive order in 2008 that calls for all city departments that deal directly with the public—not just the police—to provide interpretation services and translated documents in at least the six most commonly spoken languages in the city. Bloomberg issued that order after a campaign by community activists, similar to PVP.

Likewise, the city of Oakland, Calif., has a language access policy that applies to all city departments. That policy, established by the City Council in 2001, calls on departments to provide written and verbal communications in the languages spoken by the public; it also calls for the city to provide interpreters for public meetings if requested at least 48 hours in advance.

In San Francisco, the city certifies both bilingual officers and civilians to act as interpreters on police matters; if a designated interpreter is not available, the officer can access a translation phone line. The San Francisco ordinance, passed in 2007, urges officers not to rely on “family members, neighbors, friends, volunteers, bystanders or children to interpret … unless exigent circumstances exist and a more reliable interpreter is not available, especially for communications involving witnesses, victim and potential suspects, or in investigations, collection of evidence, negotiations or other sensitive situations.” The policy also outlines procedures to be followed in specific kinds of cases, and requires regular training of officers.

These kinds of policies are strongly supported by the Department of Justice, which has established a Working Group on Limited English Proficiency, part of a larger push to ensure compliance with the federal guarantees to equal protection across all facets of law enforcement. In a speech last year to the working group, Loretta King, assistant attorney general for civil rights, urged members to work with community advocates seeking to improve language access, and added, “We want to make it clear, to recipients [of federal funds] and federal agencies alike, that language access is not a fly-by-night measure, but an essential component of what it takes to do business and meet civil rights requirements.”

The DOJ also offers extensive assistance, including model language access legislation, to police departments and other agencies. And the department’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, or COPS, contracted with the non-profit Vera Institute of Justice to prepare a report on language-access best practices in police departments around the country.

“Communication is essential to the development of partnerships that make community policing an effective strategy for ensuring public safety,” the report, released last year, noted. “Community policing programs, in which law enforcement officers partner with community members to identify and solve problems, cannot work well when officers and residents fail to understand each other.

“Without dialog, police cannot effectively conduct investigations, build community trust, or ensure that victims will report crime. If police do not get an accurate description of problems, their responses may be unsuccessful or counterproductive.”

*

PVP members have met with Commissioner Fitchet and Sgt. Delaney about their concerns. “We felt like it wasn’t really going anywhere. So we felt the ordinance was needed to set up the system,” Rose said.

Contacted by the Advocate for his thoughts on the PVP campaign, Mayor Domenic Sarno referred questions to the Commissioner’s Office.

City Council President Jose Tosado told the Advocate that he supports the efforts, and has asked the chairs of two Council committees—Public Health and Safety, and Veterans, Administration and Human Services—to hold meetings on the matter.

“It’s a safety issue,” Tosado said. “If someone is calling for an emergency, what are you going to say—’Hang on so we can get a translator’?”

During recent budget hearings, Tosado said, he asked SPD representatives about the issue and was disappointed by their response. “I’m just concerned. It seems like they’re not worried about it. They’re not giving it enough attention,” he said.

“This is 911, for heaven’s sake,” Tosado added. “This is people’s lives.”

Tosado said he couldn’t predict whether the SPD’s rank and file would support a language access ordinance, but he hopes they would get behind it. “I think that police officers, by and large, want to do a good job,” he said. “And having access to bilingual people is important to doing a good job.”

Newman agrees, pointing to recent efforts by the SPD to strengthen its ties with the public, such as Operation Blue Knight, which sent a mass deployment of officers to the streets to improve residents’ sense of safety and connect them with the department.

“The idea of the ordinance is to be of assistance to the communities and to the police,” Newman said. “These are communities seeking greater involvement with police, and more ability to access police services. Of course, I think that’s consistent with … what the Springfield police’s outreach has been recently. …

“This ordinance seeks police involvement,” Newman added. “It’s not a criticism. It’s a way to make community and police relations better.”

That’s already a priority of the SPD, said Sgt. Delaney. And its officers, he said, are used to dealing on the spot with all kinds of challenges, including language barriers.

“Law enforcement and criminal justice and protecting the citizens—it’s not an exact science,” Delaney said. “There are glitches in the system. As cops, we learn to adapt. If I go to a call and there is a language barrier, I have so many utensils and tools that the job gets done.” The tool might be the translations services available through the department, or it might be relying on English-speaking neighbors or family members to help figure out what’s going on.

“Somehow it works out,” Delaney said. “We don’t just throw our hands in the air and walk away.”