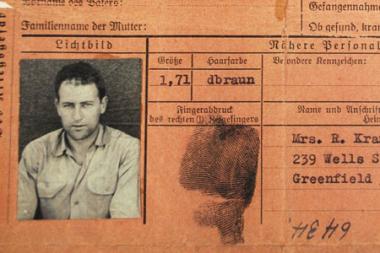

My father’s war diary is a faded blue booklet of approximately 30 pages. I did not know it even existed until the day he died, when I found myself looking through one of his old filing cabinets. My father, Harvey B. Kramer, had been a lawyer and a judge in Franklin County, and most of the drawers in the cabinet were crammed with legal documents. But in the bottom drawer, among mouldering files, I came across a document in my father’s handwriting—an account of his experiences during World War II. Alongside it was a piece of a parachute and a Purple Heart.

We knew that he had been the navigator in a B-17 shot down over Berlin, and that he had spent 10 months as a prisoner of war, but those bare facts were the only ones he had ever shared with his family. He had never shown us any memorabilia, and had never so much as hinted at the existence of a diary.

In form it is unremarkable, resembling nothing so much as a college exam book. The cover has a label printed in several languages, suggesting that the booklet may have been issued to prisoners of war by the Red Cross. The diary includes my father’s description of training in the Midwest for the 398th Bomb Group; his experience as the navigator on 12 bombing missions over Germany and France; and an account of the events of June 21, 1944. That was the day his B-17 was shot down:

At approximately 10:20 a.m., we made our turn on to the bomb run for another assault on Berlin. Wth the visibility unlimited, we were set for a perfect pattern in the heart of the city.

About 1 1/2 minutes before Bombs Away, I was tossed off my impromptu seat by a terrific jar. We immediately knew that the ship had been hit, but how badly—we in the nose did not know at the time. The nose compartment was filled with powder smoke of almost blinding intensity. A matter of seconds after we were hit, the pilot called over the interphone to make preparations for bailing out and to do so upon the sounding of the emergency bell. Upon his order, we immediately shed our flak suits and hooked up our chest packs, noticing in the meantime that our oxygen supply had mysteriously vanished. Also during this brief interval, I discovered that I had received a gash in the head which was bleeding rather profusely.

At this time the bail out signal was given and we left the ship through the nose hatch after having destroyed as much secret matter (log, radio code, maps) as possible.

My father and the rest of the crew bailed out at 28,000 feet. They had hoped the wind might carry them well away from the target area—they could see the churning smoke directly below, and the target was, after all, the heart of Hitler’s Berlin. No such luck—they drifted straight down into the middle of the city. His diary records what happened next:

I landed in a back yard several blocks west of the target, and was greeted by a civilian wielding a sledgehammer. Fortunately, I rolled with the fall to such an extent that his stroke—instead of crushing my already aching and bleeding head—simply glanced off the back of my skull-bone.

Before he could recover for another swing of his hammer, I had freed myself of my (parachute) harness, and had grabbed him by the throat. Just at this time, the Police arrived and separated us.

By this time, the blood from the wound I had received in the air had covered my eyes and face so that I had to use a strip of my chute to stop the flow.

The Police conducted me on a “forced march” thru the streets of Berlin via the kicking and pummeling method to a Police Station. This was interrupted by a meeting with two members of the Gestapo, who dragged me into an alley, where we had a veritable one-sided free-for-all.

At the Police Station, I was relieved of all my possessions, and kept in solitary confinement without food or water until the following afternoon when I was taken to an airport on the outskirts of Berlin, where I joined up with Major Killen and Lt. Rohrer [members of his crew]. Here also, a piece of flak was removed from the wound in my forehead.

During my walk thru the city, I observed widespread ruins and devastation, and the attitude of the populace was extremely hostile. I had received no food or medical attention for two days.

We left Berlin on the 23rd for the Interrogation Center near Frankfurt. Here I was placed in solitary for seven days, and interrogated four times. We were moved from here to the transient camp and thence to Sagan, where we arrived on July 5, 1944.

Fortunately, even though his metal dog tags included a stamped H, which identified him as Jewish, my father was transported to Stalag III, a prisoner of war camp in Sagan, Germany, rather than to Berga, the slave labor/concentration camp where many Jewish-American POWs were taken, and from which many never returned.

My father’s diary recounts his 10 months at Stalag III, which ended in the early morning of January 27, 1945. On that day, owing to the imminent arrival of the Russian Army, the Nazis ordered an evacuation to Moosburg, Germany, several hundred miles away. Although some of the journey was by boxcar train, most was a forced march in temperatures that at times were 25 degrees below zero. Many of the prisoners did not survive. By the time my father was finally liberated, in the spring of 1945, he had lost 70 pounds.

Near the end of the diary, my father composed a passage to which he gave the title “How True,” which included his observations on the effect of prison camp on his fellow POWs:

When many men are together for months at a time with no change of companionship and few interests outside the immediate circle that bounds them, something is sure to happen.

Tiny incidents assume gigantic proportions, little tricks of character or manner stand out in such bold relief that a new perspective is essential if irritation is not to set in. Every man sees his neighbor as he is, shorn of all patience, naked in soul, as a child sees his elders, with the pitiless, white gaze of youth. It is as though each member of the group were separated from the others by an immensely powerful magnifying glass.

After the war, several members of his 398th Bomb Group started a newsletter to stay in contact with each other and share their experiences. The group also began a tradition of annual reunions. My father received the newsletter, but he never corresponded with his old friends and never attended a reunion. Essentially, upon returning home in 1945, my father and millions of other veterans psychologically chose to close the book on World War II. On rare occasions, my father would comment that a difficult situation was still better than “hitting the silk at 28,000,” referring to bailing out over Berlin. Otherwise the war was rarely mentioned in our family.

The silence of my father and many other World War II veterans, wherever they fought, has been a collective loss to subsequent generations. These veterans chose to keep the details to themselves and move on with their lives—and one can only respect their reasons. But with the passage of time, it has left Americans as a whole with a strangely remote sense of what these veterans did, and how and why. Everyone, of course, honors the members of “the Greatest Generation”—but with very little feel for their actual experience.

The 398th Bomb Group still holds its annual reunions. World War II veterans, most in their 80s, are currently dying at a national rate of almost 3,000 per day. Needless to say, attendance at the event has been decreasing steadily. Last September, I decided to go to the reunion, which was held in Austin, Texas. Thirty-one surviving members of the 398th Group attended, along with surviving spouses and children. At one point, the organizers of the event held a question-and-answer session with the 398th group. The veterans sat at the front of the room, and, although initially reluctant to speak, each eventually provided a clear, detailed version of his individual war experiences.

Towards the end of the session, I asked the group whether they felt that succeeding generations had shown enough appreciation for their efforts and were sufficiently knowledgeable about the Second World War. It took awhile before the responses came, but the veterans spoke as one. They described their disillusionment with the American educational system because of its failure to teach history, including the details of World War II and other conflicts, which are generally reduced to a minimalist chronology. They lamented the current single-minded focus on math, English and science without a parallel effort to teach students the essentials of history. They expressed sadness and disappointment with the current preoccupation with college placement tests that exclude history. The group challenged the audience to recognize these shortcomings.

To be sure, many schools conduct Veterans’ Day ceremonies and honor those who have perished, especially recently in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as in Vietnam. Two California high schools currently devote most of a day to honor veterans in various ways. Few schools, however, have substantive curricula that move beyond chronology and statistics and bring alive the human experience of war.

One of the most prominent criticisms of the federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 is its requirement that teachers “teach to the test,” focusing almost exclusively on math and language skills. What suffers are disciplines like history. In a recent Newsweek essay, “Half a Mind is a Terrible Thing to Waste,” historian Alan Brinkley of Columbia University described the tension between the need for student achievement in math and science and the need for education in the humanities, including history. Brinkley observed that “science and technology teach us what we can do. Humanistic thinking can help us understand what we should do.”

At the conclusion of the movie Saving Private Ryan, Captain John Miller (Tom Hanks), mortally wounded, is leaning against a bridge in France. He looks at Private James Ryan (Matt Damon), whom Miller and his troops had rescued after Ryan’s three brothers were killed in action. Miller whispers to Ryan, “Earn this.”

The scene then shifts to the cemetery at Omaha Beach in Normandy many years later. Ryan, now an old man, is visiting Normandy with his family. He walks alone towards Captain Miller’s grave and says to his fallen comrade:

“Every day I think of what you said to me on the bridge. I’ve tried to live my life the best I could. I hope that at least in your eyes, I’ve earned what all of you have done for me.”

No one at the reunion of the 398th quite put it this way, but what they were saying is that, when you get right down to it, Private Ryan’s obligation is ours, too.