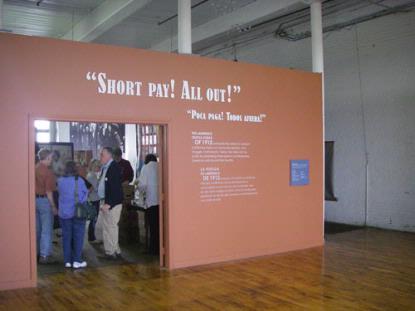

Running footsteps and shouting greet you on the stairs as you walk up to the Short Pay! All Out! Exhibit, even if you are all alone in the stairwell. You are making your way against a historic wave of women weavers, many of them recent immigrants from Poland. On January 11, 1912, upon receiving less pay than the week before, they left their stations in the four-block-long Everett Mill, streamed down the stairs and outside, shouting, and were soon joined by many others. Within a week 25,000 textile workers were on strike in Lawrence. Thus started the landmark two-month textile strike that has come to be known as the “Bread and Roses Strike.”*

The Bread and Roses Centennial Committee worked on planning the 100th anniversary of the strike for some years, and it shows in a fantastic line-up of events and happenings that is taking place in and around Lawrence this year. The commemoration has been and is a town-wide collaborative effort that stresses the collaborative nature of the strike. Nowhere is this more evident than at the exhibit, funded in part by Mass Humanities, in the Everett Mill (thanks to civic-minded owner Marianne Paley Nadel), the very place where the Lawrence Textile Strike of 1912 broke. The Lawrence History Center across the street took the lead on the exhibit, whose purpose is not so much to tell the history of the strike (done beautifully at the Lawrence Heritage State Park Visitor Center) as to raise awareness of the issues at play in the strike, and to generate community dialogue in today’s Lawrence, still an immigrant city.

Carved out of and with windows onto the raw mill space that once housed thousands of carding, spinning, and bobbing machines, looking out over the historic district in which the strike unfolded, the mill and the town themselves are on display in Short Pay, All Out! Within temporary walls, the bilingual exhibit is set up to host, accommodate and frame a series of guest exhibits and events to complement its work. Here, the commemoration opened on January 12 with a standing-room only re-enactment of the start of the strike, and here, the purpose of the exhibit is to create experience and dialogue as much as to simply inform. Some of the exhibit panels have comments by kids who have taken the tour; “I learned about the past while standing on the past,” writes Lawrence eight-grader Jazmine Rodriguez, about the floor of the mill. The exhibit is open noon to three every Thursday through Sunday, when tours are given.

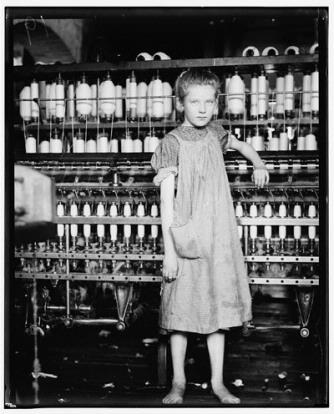

And so, on April 14, I attended a talk by Florence, MA resident Joe Manning, about photographs of child laborers in Lawrence, photographed by Lewis Hine in Lawrence in 1910 and 1911 (less than four months before the strike). Hine, who was hired by the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), a group that worked to enact legislative reform, traveled around the country for more than ten years, documenting child labor in all parts of the economy. Of all these photos, the ones of children tending machines are the most well-known. Thousands upon thousands of Hine’s NCLC photographs are available on the Library of Congress and the University of Maryland websites. I would urge anyone to explore them at random, but beware: powerful emotions may be headed your way if you do.

Joe Manning is an intrepid explorer of the local in many forms, whose work can be found on his website, Mornings on Maple Street. He has been researching Hine’s subjects for some years, after a request to research Addie Card, an “anaemic little spinner” (Hine’s notes) from Pownal, Vermont. Addie became the “poster child” for the history of the fight against child labor practices, and even graced a 1998 32¢ stamp. It’s easy to see how Manning got hooked: the contrast between Addie’s painterly face, the rest

Joe Manning is an intrepid explorer of the local in many forms, whose work can be found on his website, Mornings on Maple Street. He has been researching Hine’s subjects for some years, after a request to research Addie Card, an “anaemic little spinner” (Hine’s notes) from Pownal, Vermont. Addie became the “poster child” for the history of the fight against child labor practices, and even graced a 1998 32¢ stamp. It’s easy to see how Manning got hooked: the contrast between Addie’s painterly face, the rest of the full-length portrait of a skinny, dirty, barefooted little girl with a crooked arm, and the demonic intricacy of the bobbin-lined machine behind her is no less startling than the contrast between the fame of her portrait and the difficult life Manning’s research revealed. These contrasts sharply limn the irreconcilable contradictions between economic ideal and reality that “shamed” Americans into creating child labor laws, to paraphrase the headline of a BBC story about Lewis Hine.

of the full-length portrait of a skinny, dirty, barefooted little girl with a crooked arm, and the demonic intricacy of the bobbin-lined machine behind her is no less startling than the contrast between the fame of her portrait and the difficult life Manning’s research revealed. These contrasts sharply limn the irreconcilable contradictions between economic ideal and reality that “shamed” Americans into creating child labor laws, to paraphrase the headline of a BBC story about Lewis Hine.

Search the Library of Congress’s Lewis Hine website for Lawrence, Massachusetts, and you get 73 hits. Hine photographed approximately 80 kids in Lawrence 1910 and 1911, though his reputation had apparently preceded him and he was not able to get into the mills. Consequently, many are posed group photos of kids on lunch break. The Bread and Roses Centennial Committee easily convinced Manning to research the lives of some of these kids by sending him the picture of Eva Tanguay, now prominent in the exhibit. Manning researched ten of the photos, put them on his website (they can also be viewed in slideshow format in the gallery section to the right of this essay–the captions are courtesy of Joe Manning) and the Lawrence History Center created easy-to-read panels that reflect some of Manning’ work. He had help from a veritable posse of Lawrence researchers.** At the opening, Manning described his Lewis Hine project to an audience of about 100, and gave his report on ten of the child laborers Hine photographed in Lawrence. Manning’s exhibit at the Everett Mill will be up until at least the end of April, possibly longer.

Joe Manning with Eva Tanguay, researcher Christine Lewis, and Amita Kiley of the Lawrence History Center

It was not only a moving experience, but also incredibly instructive. The audience included descendants of four of the children in the photos. Many of the families had not known that their father, uncle, or grandmother worked in textile mills as a child; none of them were aware that Hine had photographed their relative. As one man put it, “people didn’t show their feelings then,” and they often wanted to put the past behind them in favor of a better future. Many of the children went on to lead lives in which they worked long and hard to provide enough for their children and grandchildren – fortunately in an environment where child labor was no longer tolerated – and they saw themselves as ordinary. But the families knew they weren’t, and were glad the story of their family’s labor was now being told in public.

Three generations of Endyke men.

This seems to me to be the new, new labor history, one of the great gifts of the Internet age: putting families together through time, discovering roots and degrees of separation and relatedness, and retelling the story of the heroic efforts made by workers to create the widespread wealth and well-being, the expanded middle class, that set twentieth-century America apart from the rest of the word.

Six members of the Valliere family

Lewis Hine and Joe Manning: two men creating a body of work, working with the same piece of history. But the impact of their work is different. Hine’s photographs — documentation created by a few dedicated souls–shocked and “shamed” an American middle class into supporting child labor reforms. We should not ever forget, however, that he did so in the face of bald-faced denials by industrialists – on the floor of Congress — that child labor existed in their mills. And, “out of sight, out of mind,” we have with relief put this and similar documentation efforts behind us, now that the laws have been changed long since.

Will they stay changed? Manning’s work reveals the need for safekeeping and periodically taking out our nation’s family albums — dusting off our collective memories and refreshing our collective understandings of what is right and wrong, lest we forget the details in favor of of the big picture. Our collective memory identifies the Hine photos as industrial photos, shocking pictures of small kids with big machines. If putting a child to work seems out of step with American “progress,” putting it to work tending a machine with many rapidly moving parts seems downright evil.

But Hine’s quest to photograph all American child labor led him many more places than factories alone: a search of the University of Maryland’s Hine collection for photos from Massachusetts yields 839 hits, from kids sewing tags on a stoop in Roxbury (1912), to the “Newsies” in the streets of Lawrence, and the 10-year-old Mary Gomez picking 19 pails of cranberries. Boys and girls of all races and ethnicities labored long and hard to create wealth in our own state, and boys and girls of almost all ages and nationalities continue to work, long and hard, in our world today. Do we dare to look labor practices squarely in the face? Do we respond to today’s Lewis Hines with as much shame as hindsight allows us to be shocked by the past? Are we even capable of taking in images that depict today’s laboring children?

Eva Tanguay

* If you don’t want to walk six flights to the top of the mill, take the elevator to 4 and walk up the last two floors—but if you can walk, you should walk all the way.

**Joe Manning’s Lawrence researchers: Martha Mayo, University of Massachusetts Lowell Center for Lowell History; Christine Lewis, writer and journalist; Robert Forrant, Professor and Senior Research Fellow, University of Massachusetts Lowell; Louise Sandberg, Archivist, Lawrence Public Library; Susan Grabski, Executive Director, Lawrence History Center; and Allyson Kennedy-Spencer, student, University of Massachusetts Lowell.