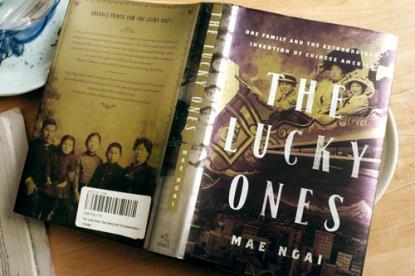

Near the end of Mae Ngai’s The Lucky Ones: One Family and the Extraordinary Invention of Chinese America, there is a paragraph that describes the surviving daughter-in-law of the story’s patriarch returning to the family home and planting a garden. The plants are listed; then, the author expands on one particular, the on choy, by noting that, in Chinese, it means, “empty heart vegetable.” Going through the account of the early Chinese immigrant family’s aspirations, tribulations and their eventual, incomplete lives, this note seems to point to the darker significance in the story than the more fulsome title of this history may suggest.

The book grew out of two events, some thirty years apart,that drew the author’s attention: one was the 1885 civil rights case of Tape v. Hurley, that forced the city of San Francisco to admit Chinese pupils into its public schools. The second was a 1915 account of a Chinese, named Frank Tape, working for the U.S. Bureau of Immigration, who was tried and acquitted for taking bribes and extorting money from Chinese immigrants. The coincidence of the rather un-Chinese sounding name was related: Mamie Tape, the pupil, and Frank Tape, the accused, were siblings, the older children of Joseph and Mary Tape, both Chinese. The cases together seem to fit well as an exemplary narrative of the Chinese struggle for civil rights and against racial persecution. But this book, richly researched and compellingly written, tells a story, or rather, a series of interwoven stories,that is more subtle and layered than can be subsumed into a schema.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, enacted in 1882 when anti-Chinese sentiments were rampant, essentially curtailed all Chinese immigrations to the U.S. for almost a century. The Lucky Ones details the varying paths the Tape family took to cope with its strictures, and, by extension, how the Chinese community, with its social advancements blocked, and jobs limited basically to laundries and restaurants, managed to survive. Especially enlightening, as underscored by the book’s subtitle, is how “Chinese America,” as a construct, came to be “invented.”

Joseph and Mary Tape came to America in the mid-1860s, at ages 12 and 11, separately, without their families. Joseph, born Jeu Tip, worked for a Scottish American dairyman in San Francisco, first as servant, then as the milk-wagon driver. Mary, probably rescued from a brothel, was given the name McGladery and grew up in a home run by missionaries, where she was educated as a gentrified young woman. In 1875, they met and were married. He moved forward to start his own horse-and-wagon business, transporting goods between the docks and Chinatown, expanding to provide paperwork for incoming immigrants, and into brokering passages. The business did very well. They built a house west of Chinatown, among mostly European Americans. Joseph was an energetic entrepreneur; Mary was a strong-minded, end-of-the-century social activist. The children played with other children in the neighborhood. The family was well assimilated.

In 1884, Mary Tape took Mamie to be enrolled in the neighborhood public school, and was refused by principal Jennie Hurley. When challenged in court, the family won Tape v. Hurley, on the 14th Amendment. The school board circumvented the decision by hastily organizing a segregated Chinese Primary School on the edge of Chinatown, and channeled the children there. They, acculturated Americans, were now consigned racially to language and social customs mostly alien to them.

On the other hand, under the Exclusion, Joseph, brokering between steamship companies and the import of goods and aliens seeking entries, thrived. In 1904, he extended this lucrative go-between work to his family by having many of them hired for the Chinese Village at the St. Louis World’s Fair. The Village, unlike national pavilions, was privately financed by Chinese merchants for profit. Located on the honky-tonk midway, it aimed at common visitors, with “Oriental” themes as its major attraction. The family ran concessions; the children were decked out as “Chinese.” When profit frayed, elaborated exotics and “beautiful Chinese girls” were proffered to draw in more crowds.

In 1906, San Francisco had the earthquake; sections of the city, and much of Chinatown, were destroyed. When it came to rebuilding, the leading merchants reflected on the appeals of the Chinese Village, the picturesque and “Oriental city of fairy palaces” were sought to entice the tourist trade. Pagoda roofs and storybook-China embellishments were simulated on old and new buildings. For the next fifty years, as China went through wars, revolutions, and social change, Chinese America, without much contact or support, conformed, for survival, to America’s prevailing race attitudes, and furnished Chinatowns across America, like dishes in restaurants, to satisfy the appetites of their clients.

Many searching Chinese Americans, now, find the disjuncture between the ethnic identity bespoke from society, and one’s experiences in personal growth, to be vexing. It is often put to victimization of being racially stereotyped. Dr. Ngai’s book points convincingly to a history that it could well be a self-fashioned identity to co-opt oppressive limitations and prejudices. To recognize this as self-constructed could help in its unburdening.

Back to the lady with the on choy: Voltaire, at the end of Candide, says: “Let us tend our garden,” meaning here: “Identities – racial, ethnic, or else – are always being constructed.” Now, with China looming and “cloud” blossoming, the interstice-world of multiple cultures could well benefit with more astute interpreters who can traverse it with new skills and enlightenment.