There’s a passage in C.S. Lewis’s book about his late conversion to Christianity, Surprised by Joy, in which he describes an aesthetic experience from his childhood that exemplifies the core of his spiritual longings. He recalls looking at Beatrix Potter’s Squirrel Nutkin and feeling a peculiar sense of desire. He describes the sensation:

It troubled me with what I can only describe as the Idea of Autumn. It sounds fantastic to say that one can be enamored of a season, but that is something like what happened; and, as before, the experience was one of intense desire. And one went back to the book, not to gratify the desire (that was impossible–how can one possess Autumn?) but to reawake it.

Surely many can identify with that experience: looking through picture books as children, seeing environments, lives, characters, and interior spaces imagined in such a way as to make one want to be in those pictures, to have a piece of it all. I can remember, for instance, looking at the cloying but well-rendered work of Joan Walsh Anglund (does anyone else remember her little books of stylized children in sweet, idyllic scenes?) and feeling the urge to neaten my room and hand wash my dolls’ clothes to mimic that charm she had conveyed.

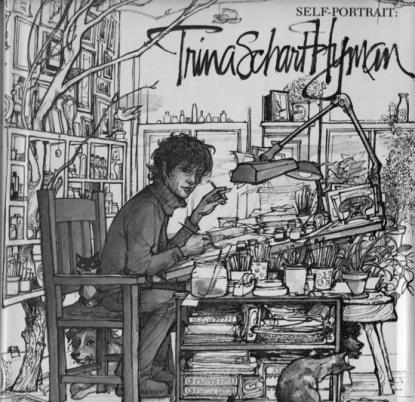

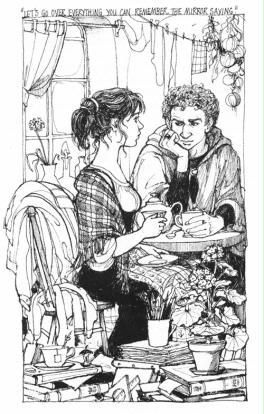

The first illustrator whose work I ever sought independently, scouring the spines of books in the children’s section of my town’s library looking for her distinctive script, was Trina Schart Hyman. Known primarily for her full-color pictures using acrylics and watercolor, it was her use of line that hooked me. Her particular flavor of facial beauty has also stayed with me. I still see children and adults whom I would categorize as “Trina-style” with vivid, dark features and lots of unruly hair. I’m looking now at books illustrated by her and trying to summon some adjectives that will express what I think is strong about her work: confident, sinuous, using multiple thicknesses of line to impart depth and distance, complete command of perspective and architecture, and seemingly created with a quickness that can only come from years of practice.

The importance of clutter in many of her domestic scenes is something else about her style that I’ve been drawn to over the years. Here is someone, like me, who loves things and is drawn to collections. She is adept at drawing refined squalor: piles of books, drawing supplies, abandoned cups of tea, and houseplants. Add a few beer bottles and dirty socks, and it could be my house.

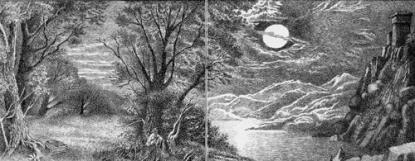

A better known contemporary of Hyman’s who has also relied heavily on line-drawing in his art,is Maurice Sendak. Like Hyman, he was devoted to detail and adept at interiors, landscapes, and figures (human and animal). His style is very different from hers, however, and he is one of those rare artists who can convey fields of tonality (skies, meadows, layers of landscape) with the use of thousands of fine and short lines–the opposite of sinuous. I will focus on his landscapes done in ink, quite simply because it’s that work of his that I love best and would most like to emulate as an artist, although I will never have his finesse, control, and patience. Take, for example, this moonlit landscape from Higglety Pigglety Pop (1967):

The multiple textures of moonlight, water, grass, sky, rock, tree: all of these have been called forth with one pen (most likely a fine-tipped Rapidograph). Shadow and chiaroscuro have also been used with varying densities of strokes for depth and creating forms that appear to have solidity. And there’s something else in this picture that provides an artistic clue to . . . what? I’d say to the level at which Sendak is loved. Can you see what I’m talking about? It’s the valise lying at the foot of a tree in the left foreground.

It is Jennie the dog-protagonist’s valise, across the water from Castle Yonder, where she will find fulfillment as a leading lady for the World Mother Goose Theatre. It is the narrative element of mystery (and a symbol of life after death I might add), and it’s the masterful element of this particular drawing.

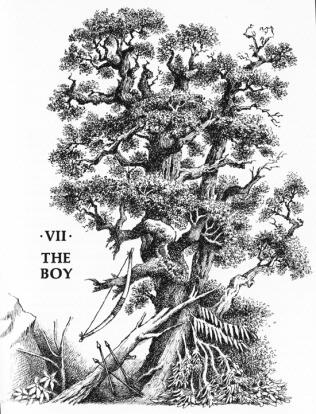

With Sendak’s recent death, there’s been plenty of appreciation expressed for his well known books. Here’s an illustration from a lesser known work that he made drawings for, The Animal Family (1965) by poet Randall Jarrell, which I picked up recently at the Forbes Library and read. I was drawn to its spine and the small, squarish, hardcover format (not seen very often these days).

The illustrations for this book, or “decorations” as the book itself refers to them, are few: cover, table of contents, and the title page for each chapter. They lack figures; all are landscapes. And yet each landscape is haunted by the impression that someone just left the scene and will soon be back. The boy in this book, who joins the household of a Hunter and a Mermaid after their animal companions, a bear and a lynx, find him in a canoe, has left his bow and arrows by the tree. Perhaps he has gone inside for lunch, or gotten interested in something else and run off, as boys will do. Absence. Something about the prose of this story as well as its illustrations suggest, simultaneously, loneliness and companionship. Every character is an orphan, and together they make a family.

I’ll close by returning to the C.S. Lewis’s invocation of “desire” as an element that was awakened in him by his experience with book illustrations. As many Lewis enthusiasts know, the concepts of metaphor and allegory are central to his fusing of literature with religion. As language is a system of symbols that evokes images and meaning in the minds of its users, so, for him, the material world we inhabit points to another plain of existence: God’s world. And I venture to guess that all people who have a fondness for picture books are moved, somehow, by illustrators’ evocation of larger worlds by their finely edited choices of what to depict on the page. Line itself creates limitless depth.

Illustrations, top to bottom, are from the following books:

Self Portrait: Trina Schart Hyman, Trina Schart Hyman (Addison-Wesley, 1981)

A Hidden Magic, by Vivian Vande Valde (Crown Publishers, Inc., 1985)

Higglety Piggley Pop! Or There Must be More to Life, by Maurice Sendak (Harper & Row Publishers, 1967)