If you think of Northampton record label Signature Sounds as strictly a folk label, well, you may not have delved far into the catalogue. And the latest effort from Valley-based Jeffrey Foucault’s side project Cold Satellite, Cavalcade, will singlehandedly go far in undoing that impression.

Foucault can and does handle an acoustic guitar with a whiskey-folk wistfulness, and he does so on Cavalcade. But the prevailing mood of the album is one of feedback- and overdrive-heavy rock. The first track, “Elegy (In a Distant Room)” bursts out of the speakers with a pounding beat and twin slabs of guitar, full of straightforward chords and whining lead. Over that relatively cacophonous background, Foucault offers a vocal with a searching, keening edge. It’s a particularly poignant combination; the melodic brand of rock that results is nearly hypnotic in its simplicity, despite lots of moving parts. Much of Cavalcade works in a similar fashion, opting for stripped-down rock in sound and structure.

In a release accompanying the album, Foucault explains, “I tried pretty consciously this time around to write tunes that brought more of my upbringing and education in early rock ’n’ roll into what I was doing. This record is a lot of four-on-the-floor rock, with only a couple blues and ballads. The first album I ever bought was Little Richard, and I wanted to make a record that reflected that.”

What may seem most incongruous about “Elegy (In a Distant Room)” is its title, which sounds a lot more like a poem than a rock song. That is, of course, exactly what it is. The loose, free-verse nature of the words makes it clear, too:

All they find is a name

Moonlight on the strait

The San Juans at midnight

The iron waves

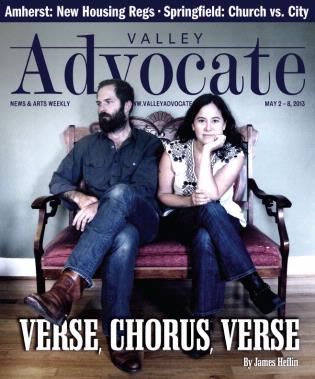

Valley poet and associate director of the UMass-Amherst MFA Program for Poets and Writers Lisa Olstein is an integral part of Cold Satellite, offering Foucault poems as starting points for his songwriting. The two, who are old friends, first collaborated in this way for the 2010 album Jeffrey Foucault: Cold Satellite.

Olstein says, “Jeffrey and I have been friends for years and each of us is interested in each other’s genre: he reads a lot of poetry (and fiction, and history, et cetera) and music has always been a hugely important part of my life (as a listener).

“Back in 2007, I’d just published my first book of poems and he was between albums. I gave him some poems that didn’t make the cut for my book but that I still liked, a few poem fragments, and also a piece I’d written intentionally to be song lyrics—an experiment for me. I figured, if anything, he’d mine the material for parts, but instead, what was interesting and musically productive for him was to use the words—mostly unchanged, although sometimes elided or rearranged—as leaping-off points.”

Foucault’s process transformed her words into songs quickly. “He’d read them fast, with a guitar in hand and a recorder on the table, letting them evoke mood and melody and rhythm,” says Olstein. “He did this first with one poem that I’d taken out of my first book—just picked up a guitar in a hotel room in California and wrote while reading. He played a demo into my answering machine. We were both curious and moved forward from there.”

For his part, Foucault says, “I curate the language, essentially. More often than not, I’m trying to reduce. Some songs on the new record, I cut out three or four verses and I took something she might have labeled ‘chorus’ or ‘refrain’ and made it a verse, and made one of the verses the chorus. The essential thing about what we do is that I don’t ask her what the poems are about until well after the record has been recorded. I take those poems and fragments and lyrics, and most of the time I try not to even read them until I have a guitar in my hands.”

Sometimes that leads to particularly interesting results. The second track, “Necessary Monsters,” is a shuffling blues tune. Well after the song was recorded, Foucault asked Olstein what it was about.

The result? “…That’s my first blues about pregnancy,” says Foucault. “I try to sing it with conviction. But the ambiguity is important. It leaves room.”

Olstein sends Foucault poems, but she’s also undertaken writing words meant to be song lyrics. She offers a clue to which songs started as poems, which as lyrics—the lyrics rhyme, and the poems don’t. In purely poetic terms, Olstein is very much a contemporary poet, mostly eschewing traditional bounds of form and regular meter for unhinged and sophisticated imagery that possesses a music with its own logic and rhythm, even if it’s not the sort you’ll find in sonnets of yore.

When Olstein speaks about the collaboration, it’s clear that freedom from any particular form and a readiness for surprise are part of what she enjoys.

“I send along written pieces—poems I think might lend themselves to becoming lyrics, pieces written as lyrics with Jeffrey in mind…. We don’t really talk it through—he chooses what he chooses of what I send, and I’m almost always surprised by where he takes things,” Olstein says. “A lyric I’m sure is going to be a crooner ends up being a rocker and vice versa. So, for me, there’s a feeling of blind faith—I trust Jeffrey’s aesthetic and approach—and a certain amount of wonder. The process feels almost alchemical, where these two distinct parts come together and make something else, a third thing.

“I’m very often surprised by the life the words take on in the songs they get to become,” she continues. “It can make for an excellent experience of prediction error signal: mostly I’m really delighted to encounter something unanticipated—isn’t that part of what we need and want from art and from art-making?—and I value the way our collaboration forces that issue, makes it integral. Together we end up making something unlike what either of us makes on our own.”

For Olstein, the widespread exposure that comes courtesy of Cold Satellite’s Cavalcade is a particularly well-timed thing—her third book, Little Stranger, is due out in May from Copper Canyon Press. Reading Little Stranger is quite different from reading her lyrics in a CD sleeve. In it, Olstein’s words arrive in a roomier context, and her poems take brain-tingling flight as self-sufficient pieces of writing; readers who start with Foucault’s audio will find nothing lacking in her work on its own.

Olstein says working with Foucault in what she dubs a “collaboration at a distance” hasn’t significantly changed how she thinks of or goes about writing. But, she says, “I do love having the possibility of this dynamic exchange and second life for some of the poems, and I also really enjoy writing song lyrics, too. It’s provocative in terms of my thinking about genre, form, boundaries, rules, and, more significantly, in terms of what moves us and how and why.

“Plus, when I put in the disc and hear one of my favorite singer’s new batch of songs, I already know all the words.”•