When documentary filmmaker Larry Hott asked me if he might borrow some of my Frederick Law Olmsted books, I was both honored and a bit protective. I’ve known and enjoyed the many documentaries Hott and his partner Diane Garey—also his co-producer, editor and wife—have made, but their other films were on subjects I didn’t know much about.

But now Hott Productions was embarking on a documentary about a subject that was personal to me: the genius behind Boston’s “Emerald Necklace” and Manhattan’s Central Park.

Like so many living in and around New York City, I grew up with a firm sense of ownership of Central Park. From early on, I knew the place was mine.

Even as a kid, I was thrilled by the notion that as a member of the public, the place had been built just for me. Like everyone around me, I could do with it just as I wanted. No stretch of field, forest or waterway was off limits. I could crawl on the statue of Alice in Wonderland or play hide and seek in the Ramble, the wooded hill on the northern side of the boat pond.

In middle school, I remember—ever the wiseass—telling a friend visiting from overseas that the park was created originally as an Indian reservation and was still used that way. I didn’t plan to fabricate a story. Not really knowing the details of its construction myself, though, this notion seemed far more plausible than a group of bureaucrats getting together and saying, “Let’s do something enchanting, sweeping and profound that will benefit generations of people of all walks of life for the rest of time.”

(My foreign friend thought so, too, and accepted my explanation without a thought. Apparently she wasn’t disabused of the notion until years later.)

Not until I was nearing college age, though, did I begin to understand that the sights and scenes I loved most about the park were not happenstance at all, but carefully constructed to provoke me in certain ways. Curvy, twisted lanes and stairways in a dense forest for mindful, inward contemplation. Vast, sky-embracing pastures to bound about in, enjoying the sensuousness of open space.

I only came to this awareness, though, through visits to both this country’s magical kingdoms, Disney World in Florida and Disneyland in California. I was particularly enamored of the Jungle Safari and how on both sides of the continent there could be nearly identical rides which are so immersive and utterly believable (at least to a kid). I wanted one in my own back yard and tried to figure out how to go about creating it. Reading about how these amusement parks were carefully designed to shield visitors from the uglier side of maintaining the magic, I began to see that similar planning had been at work in Olmsted’s parks.

It didn’t hurt that my dad, an architect, was part of the team working on a 1980s-era renovation of Central Park. Through his research and my own, I became fascinated and inspired by America’s father of landscape design. He became a personal hero.

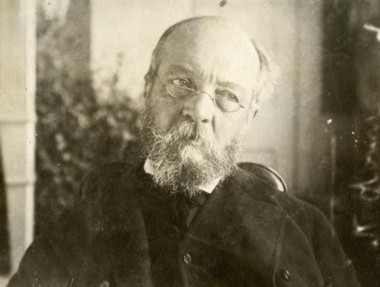

Olmsted, who had only been a journalist and unsuccessful farmer before starting work on the park, executed plans that required leveling great rocky hills and making lush, endless fields out of swamps, shantytowns and forests. He worked in close collaboration with his partner, architect Calvert Vaux, but it was often Olmsted who was on site to direct the legions of workers, wagons and horse-powered machinery. Though the success of Central Park kept him busy for the rest of his life, he was never fabulously wealthy or revered so greatly that his ideas were ever accepted without heated argument. He lost as many battles as he won.

Indeed, almost every large-scale project he undertook—Prospect Park, the Buffalo Park System, the Emerald Necklace around Boston, the national park for Niagara Falls—was met with soul-crushing bureaucratic battles. His vision, as we can now all clearly see, was long-term and magnificent, embracing not just years but decades and centuries.

Where Olmsted saw a rejuvenating meadow that could be enjoyed by anyone, businessmen and builders often saw available space they could sell for a high return. Even if he was able to convince one set of elected officials that leaving his work unaltered was the best approach, more often than not, he’d have to renew his arguments with the next administration.

Not only did he accomplish the impossible in physical, engineering terms; Frederick Law Olmsted did much of his most brilliant work while “educating” the rich and powerful who almost always felt they knew better.

F rederick Law Olmsted: Designing America is a loving portrait of the man. Directed by Hott and written by Ken Chowder, it is narrated by Stockard Channing and includes the voices of dozens of passionate Olmsted experts—not just biographers and academics, but many of those involved in the modern day upkeep and management of the parks. It offers a highly detailed yet sweeping view of one of America’s greatest visionaries.

Illustrated with a wealth of rare historic photographs and animated versions of his drawings and diagrams, the film also contains some of the most evocative photography of Olmsted’s landscape works I’ve seen. Shot in all seasons and at many times of day, the outdoor video captures the many moods of the parks, and does it with lingering pans and slow zooms that reflect the relaxed pace of the spaces Olmsted and Vaux created.

Still, despite Channing’s comfortable drawl and the lingering camera work, the film packs a lot in during its hour-long running time. Not only was Olmsted famous for his parks, but he took on a host of other professions, many of which he excelled at. Before the Civil War, he was a news correspondent for the then-fledgling New York Times, describing his journeys through the South. During the war, he helped develop the ambulance and nursing stations that would later become the Red Cross. While managing a gold mine near San Francisco into bankruptcy, he discovered Yosemite and the great Sequoia trees of the Northwest. He was among the first to declare a need to protect these places—to consider them public and beyond value.

Though I may have felt guarded when Larry Hott asked to borrow some of my Olmsted books, I shouldn’t have worried. He and Garey understand Olmsted’s brilliance and make him shine as brightly as he deserves. They make you eager to go out enjoy Olmsted’s masterpieces with a new appreciation for their mastery.

They also made the connection between Olmsted and Disney.

What they didn’t include, though, is that the comparison between the two men isn’t coincidental. Before Walt Disney was born, his dad had gone to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which featured a waterway and landscaping by Olmsted. The lagoon with Venetian gondoliers that he had created out of a swamp was surrounded by giant white buildings with pillars and other classical stylings. Years later, the elder Disney would tell Walt and his siblings all about the magic he’d encountered in that magnificent White City on the shores of Lake Michigan.•

Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing America is a production of WNED-TV and Florentine Films/Hott Productions, Inc. The local premiere will be at the Academy of Music in Northampton on April 13. the film will be broadcast nationally on PBS June 20.