Kelly Link’s stories are weird in the best possible sense of the word. They often take place in unusual settings that aren’t quite like consensus reality — a hotel hosting a superhero convention, a summer house inhabited by mysterious and possibly malevolent creatures, a handbag containing a fairy village. Link treats the fantastic elements of her stories with plainspoken prose that makes the line between “real” and otherwise fade to irrelevance. It’s a deft trick, and one that will find you utterly absorbed in her micro-universes in short order.

Put with her straightforward sentences regular eruptions of top-shelf wit (e.g., “Everybody naked, nobody happy. It’s Scandinavian art porn”), and it’s easy to see why reviews of her work tend to be dramatic. Neil Gaiman called her “a national treasure,” and The New York Times Book Review called her “a sorceress to be reckoned with.”

Kirkus Reviews said of her latest collection, “Exquisite, cruelly wise and the opposite of reassuring, these stories linger like dreams and will leave readers looking over their shoulders for their own ghosts.” And Publishers Weekly: “Like Kafka hosting Saturday Night Live, Link mixes humor with existential dread.”

Link, a longtime Northampton resident, also runs Small Beer Press with her husband, Gavin Grant. She has, at least so far, pursued an unusual route in her writing career — she has published only short stories, some of them via Small Beer. About her story-centric approach, Link says, “Writing only short stories is kind of a weird thing to do. I’ll admit it. The up side, though, is that you get attention for not doing the usual thing.”

She adds, “Maybe I write short stories because I have a short attention span. Maybe it’s because as a reader, I have a slight preference for short stories over novels. Maybe it’s because as an editor for Small Beer Press, I get to work with novelists on their books, and that has satisfied whatever impulse toward the novel I might have.”

Link’s earlier collections Magic for Beginners and Stranger Things Happen were published by Small Beer. It was an unusual move that allowed Link an equally unusual amount of control over the product and the process. The first, Stranger Things Happen, put Link on the literary map in a big way.

“I know I’ve been unusually lucky,” Link says. “We didn’t necessarily expect that publishing my first collection would make a splash. What we hoped was that we wouldn’t lose money, and that it would help us work out some of the kinks that you run into when you start off publishing books. We hoped that we could produce a reasonable facsimile of a book, with the help of good cover art, professional copyediting, and good distribution, that wouldn’t look out of place in a bookstore or on someone’s shelves.

“An early review from Laura Miller on Salon.com helped the book break out,” she says. “Every part of the publishing experience was miles better than I could have anticipated, but we worked very hard, too, to make sure that we didn’t muck it up.

“Publishing is a weird business, especially small press publishing. I don’t recommend self-publishing (autocorrect just changed that to self-punishing, by the way) unless you’ve done a lot of research, have reasonable expectations, and are willing to spend money on a designer and a good proofreader.”

These days, Link’s steering a new course that renders the “why short stories” question moot. “I’ve sold a novel to Random House and now I’ll have to write it,” she says. “So I guess the question will now become, ‘Why a novel?’ To which I’d respond that my short stories have been getting longer in the last few years, and I wanted a new kind of problem to solve.”

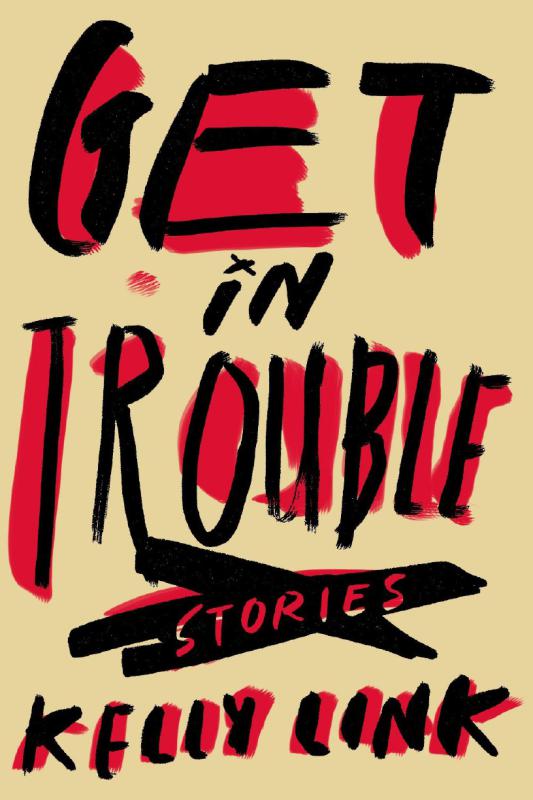

With her latest book, just out from Random House, Get in Trouble, Link delivers the first collection she’s published in several years. It’s an astonishing read. It’s also one that defies the misguided souls who insist on dividing literature into narrow genres. Though Link began with notions of genre, the results are quite far afield, in ways that expand or obliterate the definition of science fiction and fantasy. “What I had in mind when I started writing was to write in the classic science fiction, fantasy, and horror modes,” Link says. “It’s pretty much still where I start off. But writers don’t necessarily get the final word on how they’re described or where they’re shelved. I write ghost stories, I write young adult stories, I write stories with weird things in them.”

To write science fiction, fantasy, or horror, a writer faces a central and demanding task: how do you bring readers up to speed on the world you’ve created? Some writers, particularly those who blazed the trail in science fiction decades ago, do it in a ham-fisted way, offering sprawling histories and descriptions of their created universes. The results are often deadly dull — Arthur C. Clarke, a widely respected SF pioneer, sometimes went many pages (in one case, 100-plus) into a work before describing a scene or introducing dialogue.

Link dispenses with such up-front stuff entirely. To read one of her stories often requires an approach like leaping into cold water. There are no preambles or apologies; readers must get up to speed via more subtle means. That can create a period of disorientation, but Link provides context in clever ways, dropping references and later explaining them, or letting glimpses of the world accrue until the larger canvas is revealed. That approach demands a remarkable level of awareness and control on Link’s part, and she never fails to deliver.

The prose in her stories is nearly always simple. It makes the whole enterprise go down easy. When Link arrives at a visceral truth, she often points it out with almost childlike language. In “I Can See Right Through You,” a tale of former movie stars who reunite at a nudist camp site where one of them is filming a ghost-hunting TV series, she offers: “It is worse, somehow, to be naked in the dark. The world is so big and he is not.”

When moments like that arrive, they arrive with a pathos made all the more devastating by their simplicity. Those moments are inevitably surrounded by surprising asides and dead-on descriptions as funny as they are unexpected. In “Secret Identity,” Link writes, “It’s eleven o’clock on a Friday morning, and at that moment the girl in the lobby is missing third-period biology. Her fetal pig is wondering where she is.” Later on in the same story, she says, “Once someone has saved your life, they might as well fall in love with you, too. It’s just good economics.”

For Link, stories are problems in need of elegant solutions, and she solves those problems at macro and micro levels. “I want to come up with an interesting kind of narrative problem to solve, whether it has to do with point of view, or structure, or a certain kind of twist that I don’t want the reader to guess,” Link says. “Secondly, I want to do this in a way that will be entertaining for the reader. Finally, I want to make the story to be as good as I can make it, sentence by sentence. I think a good story can be read more than once, and that a good story has a kind of openness to it that allows the reader to find their own particular meaning.”

That sense of openness pervades her work. Even when a plot seems ripe for a particular revelation, Link tends to deliver something that instead deepens the mystery, offering a sense of completeness without making things too easy or expected. Her stories are indeed able to withstand multiple reads, and with each, the mysterious seems ever so slightly more accessible.•

James Heflin can be reached at jheflin@valleyadvocate.com