It was on a year-long walk retracing the path of slavery between Africa and the United States that Teegrey Iannuzzi says she finally woke up.

She was taking part in the Interfaith Pilgrimage of the Middle Passage, a walk retracing the trans-Atlantic slave trade between South Africa and the American colonies. The trek began in 1998 and was organized by Leverett Buddhist Sister Clare Carter, who meant for the journey to unite people of various racial and religious backgrounds in a visceral understanding of slavery’s cost.

Iannuzzi, now in her late 40s and living in Shutesbury, was already interested in racial harmony. But she didn’t realize how much work had to be done to realize that goal until she spent month after month not walking in other people’s shoes, but right beside them.

“When a peace walker of African descent told me that a day doesn’t pass that she is not confronted with racism in her life, I was shocked,” said Iannuzzi, who is white. “But how would I know what it was like being black in America?”

More importantly, she said, Iannuzzi wondered what she could do to level racial disparities in America. Iannuzzi says she knows that she’ll never truly be able to understand the black experience.

“I benefit from this system of privilege at the expense of people of color,” she said. “I am responsible to do my part.”

For her part, Iannuzzi got in touch with some like-minded friends and co-founded Mass Slavery Apology, a Greenfield-based organization dedicated to white people making amends to black people for the suffering of them and their ancestors. The friends — Iannuzzi, Anne Keough, and Sharin Alpert — spent four years in consultation with leaders in the black community drafting an open apology to black people. The statement now resides online at www.massslaveryapology.org. Hundreds of local people have signed on to the statement.

However, the founders and current members of Mass Slavery Apology would be the first to tell you the apology means nothing without action to right the wrong — action that includes not only words but also some form of financial reparations.

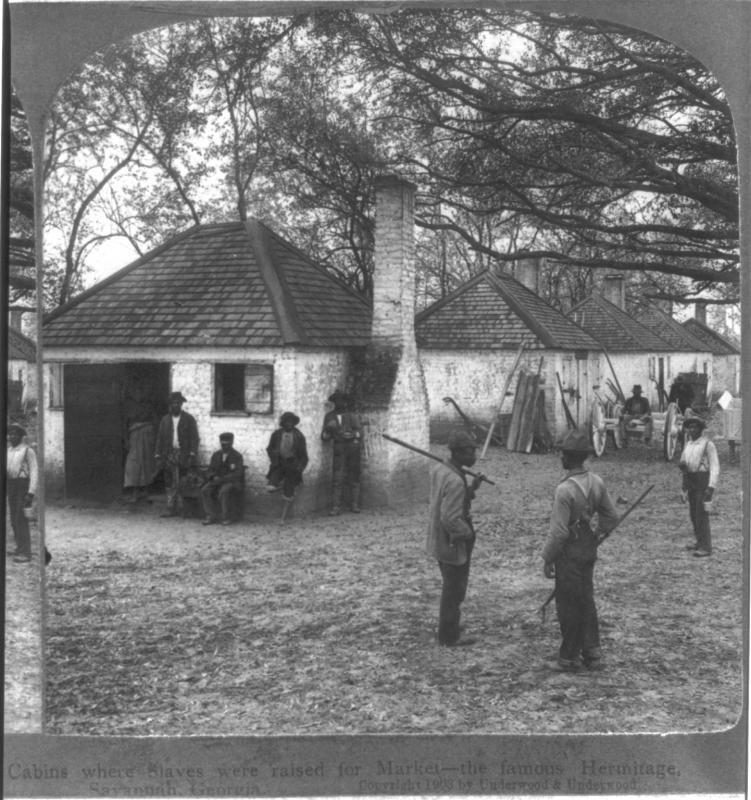

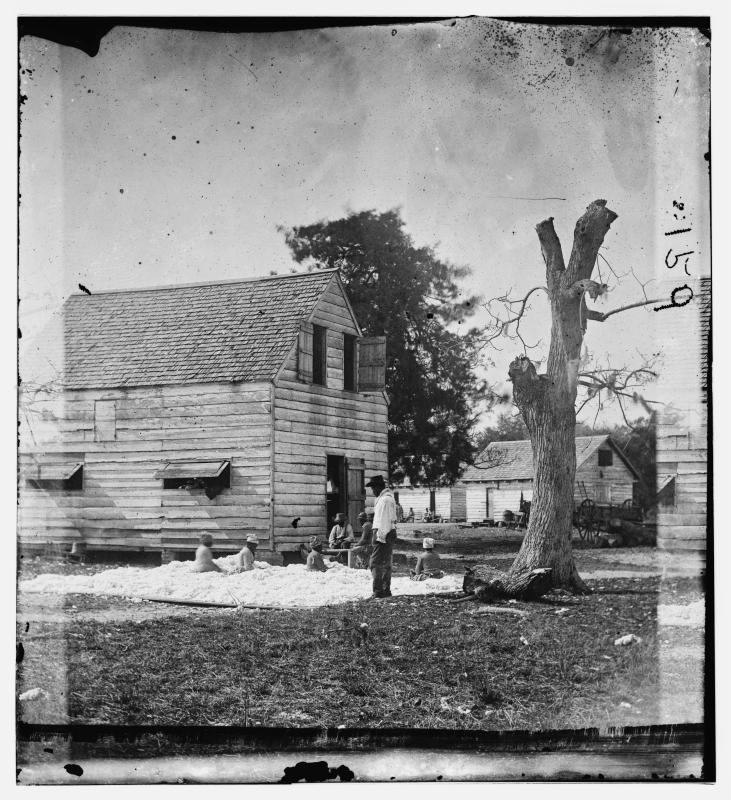

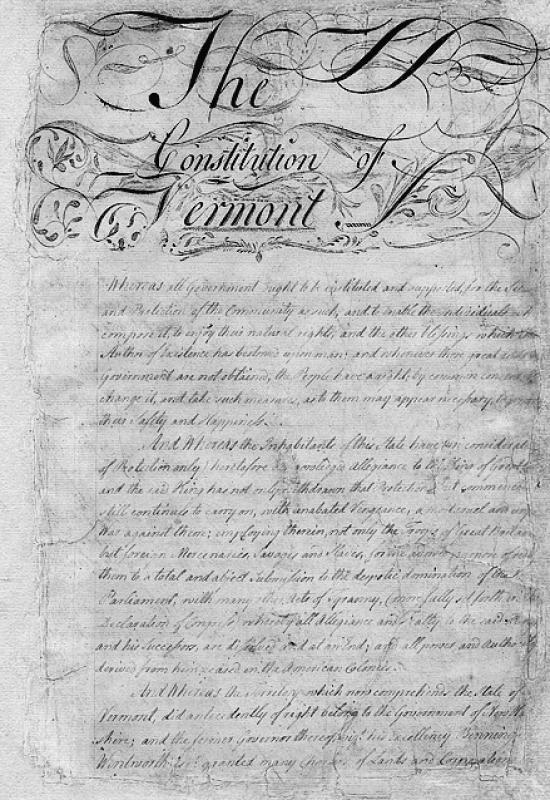

Reparations would compensate black people for their forced labor, pain and oppression. A 2004 Harvard University study, Documenting the Costs of Slavery, Segregation, and Contemporary Racism: Why Reparations Are in Order for African Americans, estimates that in America black people have been cheated out of $5 to $24 trillion in wages, other compensation, and potential interest since the days of slavery, an institution that became legal in British America in the 1660s.

It’s unclear where the money to pay for reparations would come from, but most likely the taxpayer would foot the bill.

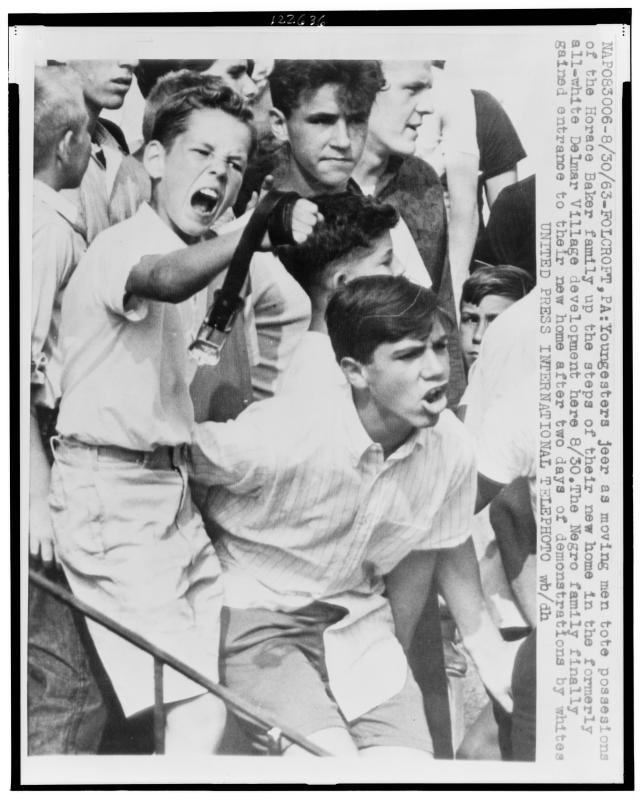

The first step to getting people to support reparations is to educate white people about how racism’s stranglehold on the black community didn’t end with slavery and that white people today are still benefiting from forced labor and segregation. Also, it’s important for white people to understand why they should care.

And this is just what Mass Slavery Apology is trying to do, bring about reparations by educating the white community about how reparations will benefit black and white people. The group holds monthly informational meetings about racial and social inequity and provides an online resource for historical information about slavery.

“Better information leads to better behavior — sometimes,” said Enoch Page, the main consultant on the apology statement. Page, who is black, spoke to the Advocate by telephone from his home in California, where he is a full-time Americorps volunteer. Prior to this, Page lived in the Valley, working with civil rights activists and teaching anthropology and education at UMass Amherst.

Page said knowledge is not the silver bullet to creating change, but it’s the best weapon civil rights activists have in the fight against racism.

“You don’t necessarily get a good return on education, but without it your chance of better behavior is slim to nil,” he said.

Page said he admires what the co-founders of Mass Slavery Apology have accomplished. He describes the women as “models of what it would be like for other white people to recognize that they have a collective debt that they owe to people of color in this country.”

Getting people to talk about reparations — let alone get a serious proposal on the table — is difficult work. Iannuzzi said MSA is often met with a mixed reaction from the public — everything from gratitude to curses.

“A common question from the public has been: ‘Apology? Why should I apologize? I didn’t create in the institution of slavery. Beside, my family wasn’t involved. My ancestors came to this country after slavery.’ ” Iannuzzi tries to remind people that white people benefit from a system that was established during slavery and has lingered in ways big and small.

“Whites get privileges and access to resources that have been repeatedly denied to people of color even long after slavery ended,” she said.

What are reparations?

The goal of reparations would be to help fill the wealth gap between white and black people through infusing wealth into the black community.

The financial disparities between white and black people are immense and block opportunities for upward mobility. For example, in 2011, white households had a median income of $50,400 per year compared to just $32,028 for blacks, according to The Racial Wealth Gap report by Demos, a nonprofit think tank based in New York.

That same year, the report states, the median white household had about $111,146 in wealth holdings, compared to just $7,113 for median black households. And about 73 percent of white households own their own home, compared to 45 percent of blacks.

Helping black people buy homes and secure better jobs with fair wages through education and policy changes would help raise the community onto a level playing field, say reparations advocates. One such policy is “red-lining,” the practice of denying loans for homeownership to people who live in neighborhoods considered too poor to be a good loan risk.

If redlining were quashed and homeownership rates were more equal in the U.S., median black household wealth would grow $32,113, and the wealth gap between black and white households would shrink 31 percent, according to Demos. Homeownership increases financial stability and grows wealth because instead of paying rent to a landlord, the homeowner is building equity.

Getting the wealth out

There are two primary schools of thought when it comes to disbursing reparations: doling out a lump sum of cash or establishing a trust that would distribute wealth over time and according to specific criteria.

The distribution of lump sums of money to black people has its pitfalls, said Dania Francis, a UMass professor of economics and Afro-American studies and co-author of the 2010 paper, “Reparations for African-Americans as a Transfer Problem: A Cautionary Tale.”

If reparations were awarded today, she said, the money would most likely be spent to pay bills, on goods or services, invested or saved. While that would benefit the black Americans who initially received the money, a relatively small percentage would flow to black-owned businesses — because there aren’t very many of them.

According to 2007 Census data, the most recent information available, 7 percent of American businesses are owned by black people, while 78 percent are owned by whites. Just about anywhere the money was spent, the cash would end up back in the hands of white America.

“Let’s say you have all these intentions of not going out and spending it on whatever. You’re going to save it or invest it. Where is that investment going to go?” said Francis, who is black. “Right back into JP Morgan.

“The whole point of reparations was to improve the relative standing of blacks in America. This wouldn’t get it done.”

This led Francis and others to study the possibility of establishing a reparations trust fund. Under that scenario, black people could apply to for the purchase of a house, to start a business, or get an education.

The trust fund idea is the more politically popular form of reparations — if any form of reparations can be called popular. For example, a recent YouGov survey found that while only 6 percent of white people surveyed thought black people deserve cash reparations; 19 percent said they would support reparations in the form of education and job training. The same survey found that 59 percent of black people surveyed were in favor of cash reparations while 63 percent were in favor of educational investments.

Don’t mention it

With reparations there are still many questions: How much money would be enough to make a difference? Who would be the recipients? How long would the program last? Where would the money come from?

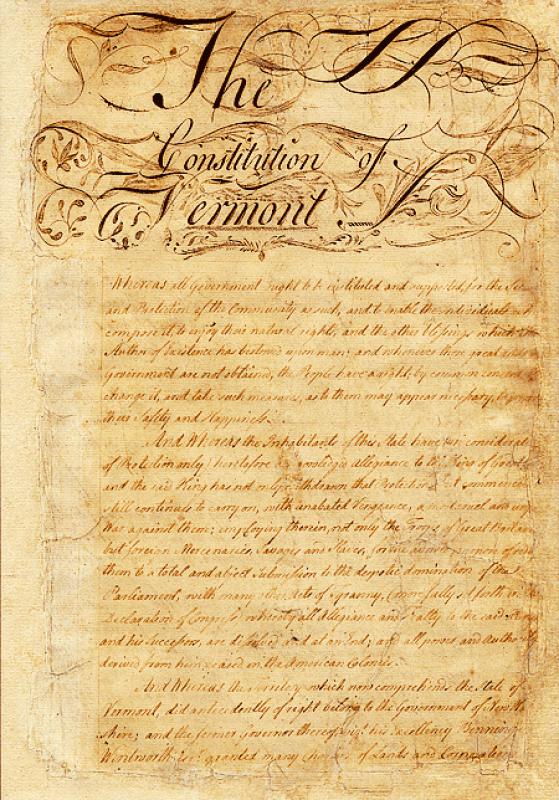

None of them have answers — the U.S. isn’t even clear on how slavery and the legacy of segregation and racism have affected black Americans and the country as a whole. Study of these questions has been blocked over and over again.

A discussion about reparations in the U.S. is near impossible to have. According to a January 2014 YouGov poll, 68 percent of Americans don’t think cash reparations should be made to descendants of slaves. In this climate, Michigan House Rep. John Conyers, Jr., has introduced legislation to fund a study on how slavery has impacted the social, political and economic life of the U.S. in each Congress since 1989. And every time, the legislation has been relegated to a committee, then a subcommittee, never to be heard from again until Conyers introduces it at the next Congress.

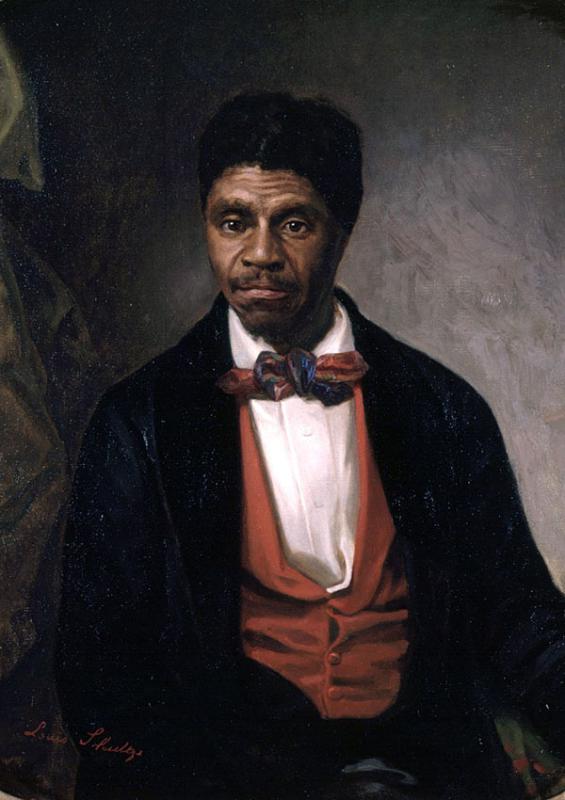

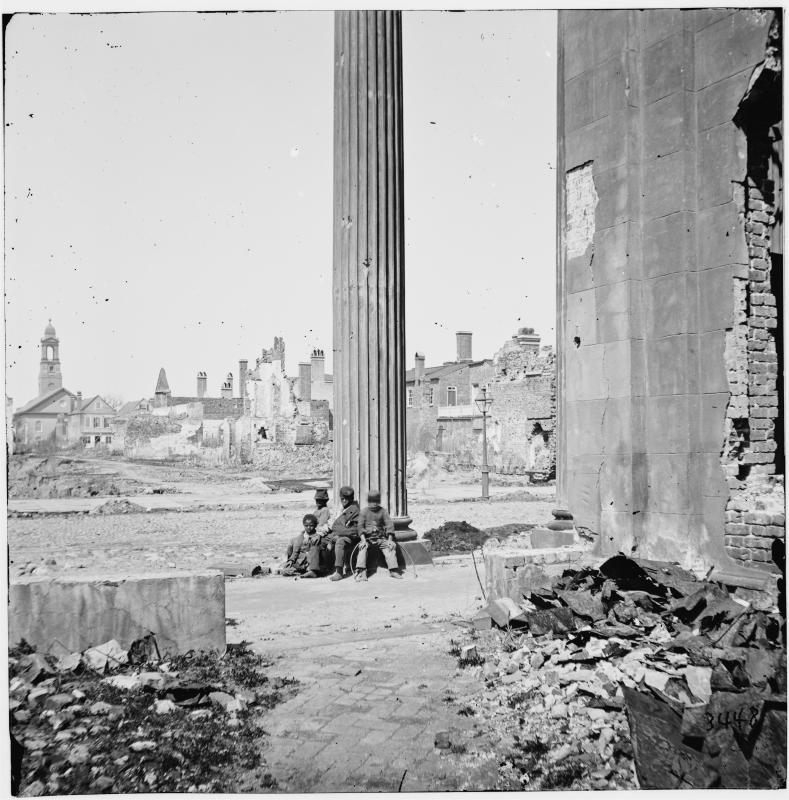

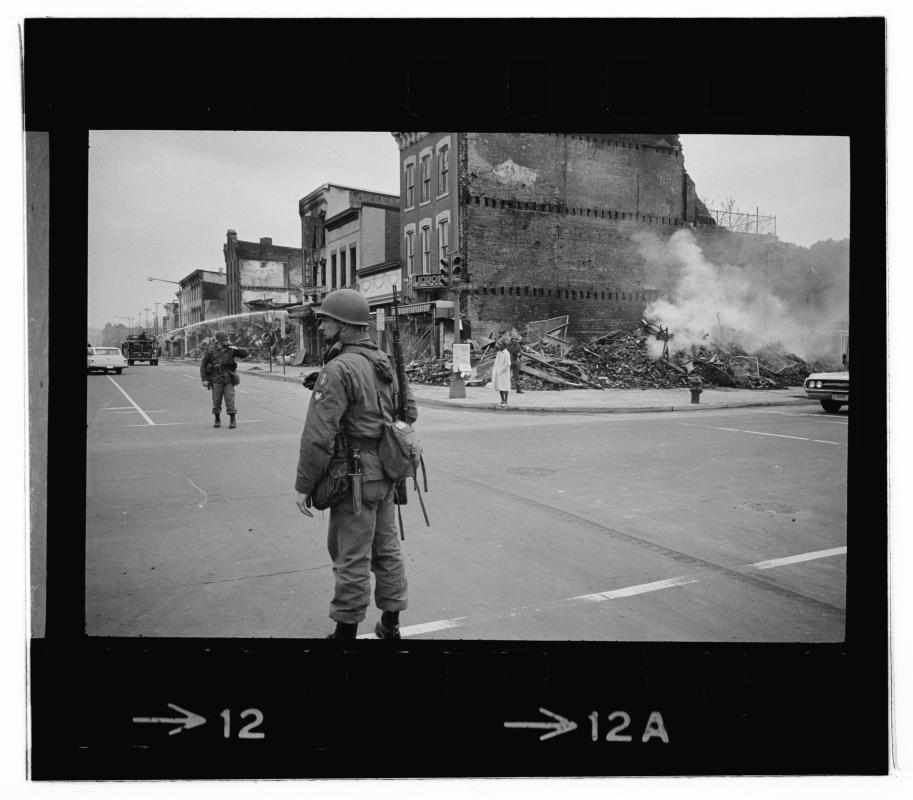

Oppression of black people didn’t cease once President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. It carries on today. Consider:

While the chances of a white American male being imprisoned at some point in his life is 1 in 17, a black male faces a 1 in 3 chance.

African Americans comprise 14 percent of the nation’s regular drug users, but are 37 percent of those arrested for drug offenses.

The average lifespan of a black man is almost five years shorter than that of a white man.

Still, opponents characterize reparation as unnecessary. In his seminal anti-reparations article, Ten Reasons Why Reparations for Blacks is a Bad Idea for Blacks — and Racist Too, David Horowitz, a conservative writer and think tank founder claims that very few black people were hurt by slavery and its legacy. He says the black community was repaid for any damage a few white slaveholders may have done by welfare and other policies advanced by the civil rights movement, despite the fact that more white people have taken advantage of welfare than blacks. For example, in 2012, the most recent information available, 38 percent of households receiving foodstamps were white, while 24 percent were black.

“If not for the sacrifices of white soldiers and a white American president who gave his life to sign the Emancipation Proclamation, blacks in America would still be slaves. If not for the dedication of Americans of all ethnicities and colors to a society based on the principle that all men are created equal, blacks in America would not enjoy the highest standard of living of blacks anywhere in the world,” he wrote. “Where is the gratitude of black America and its leaders for those gifts?”

Page, the reparations supporter, says that while western society is “terrified” by reparations, they are a necessary next step. “Reparations are in order. I do believe a serious effort to make reparations to the whole population, not just to individuals, would have a tremendous impact on African American consciousness.”

He also notes that should reparations be paid, the money would not be in exchange for black people’s silence on racism and researching slavery’s legacy.

“The problem with reparations is that it can be seen by the dominant population as pay off, and now that we’ve paid you off we don’t want to hear from you anymore,” Page said.

In this climate, members of Mass Slavery Apology say they are compelled to keep working. In addition to the statement, members organize monthly educational events exploring racial injustice. The next one will be held April 7 at the First Congregational Church in Greenfield. The guest speaker is a black mother who will discuss the special challenges she faces raising a black son in America. MSA isn’t just interested in racial justice for black people, though that is their focus. They are also interested in the shabby treatment Native Americans and Latinos receive in the United States. In May, the MSA will hold a talk about Latino history and experiences.

“White people, for our good and for the welfare of people of color, we need to recognize a debt is owed,” said George Esworthy, one of seven active MSA members. “The only lost cause is the one you give up on and the struggle for reparations has gone on for a long time. It’s persistent and under the radar and we can’t give it up.”•

Contact Kristin Palpini at editor@valleyadvocate.com.