Attending a Veruca Salt concert as a teenager in the ’90s, Tanya Pearson never imagined that 20 years later she’d be asking lead vocalist-guitarists Nina Gordon and Louise Post about sexism in the industry.

A photo documenting Pearson’s reunion with the two band members last year — she interviewed them for the Women of Rock Oral History Project she started at Smith College — shows her squinty-eyed and beaming with fangirl excitement.

Pearson, 34, had to visibly recover when I told her I’d never heard of the band. “Well,” she says, seeming to take a sort of zen breath, “that’s why I’m doing this.”

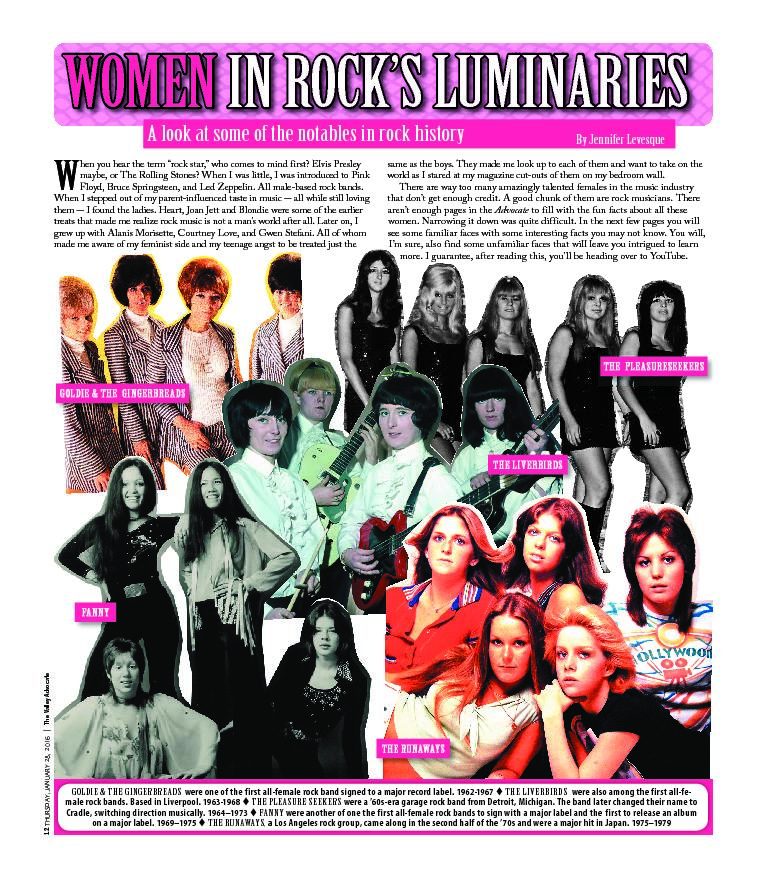

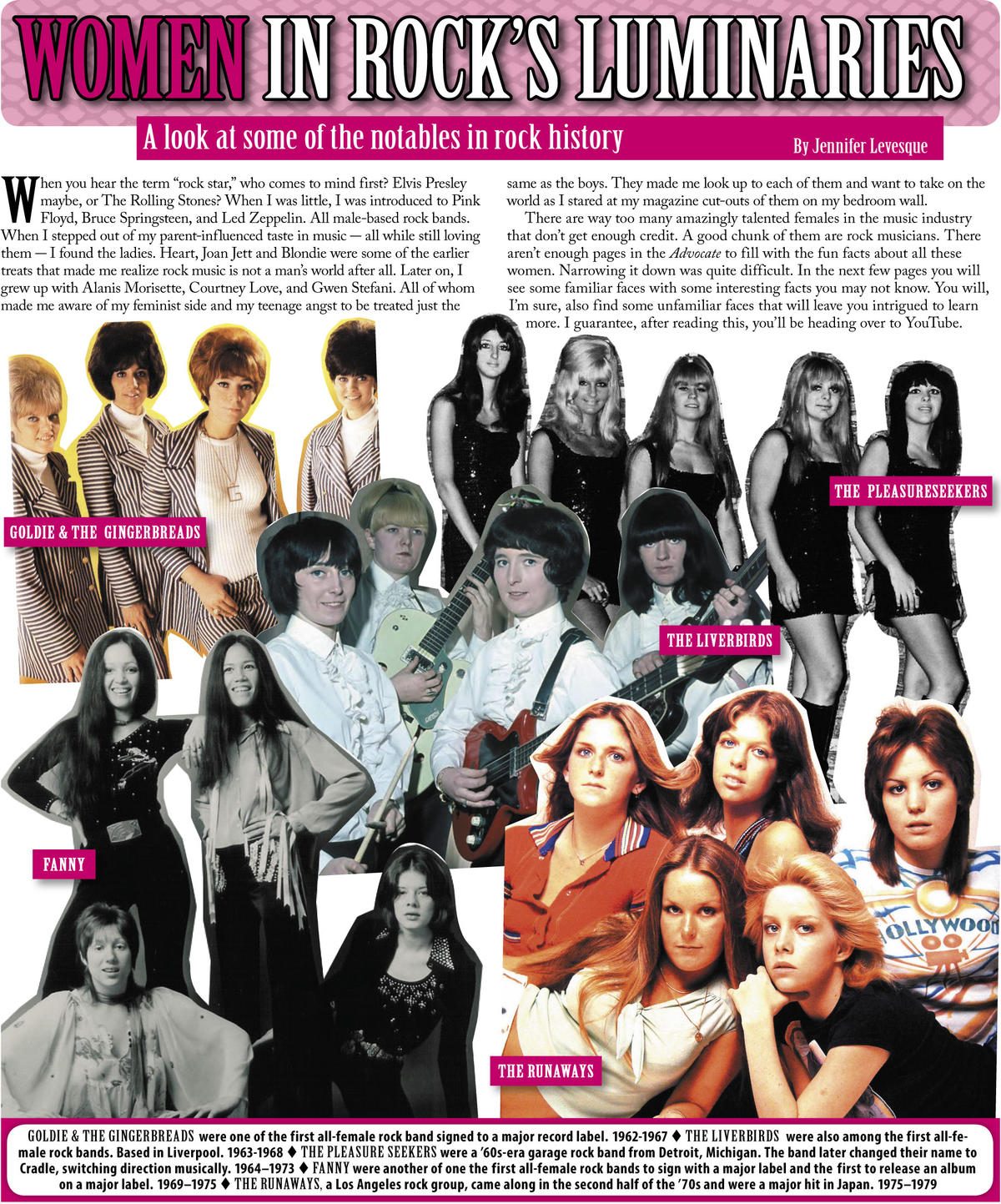

Inspired by the lack of information out there about the women who were profoundly influential in her own musical career, Pearson started interviewing iconic female rockers about a year ago to form a collection that will accompany Smith’s Voices of Feminism Oral History Project in the Sophia Smith Collection, where the ten interviews she’s gathered so far are being digitized and put online for all the world to see. It’s widely acknowledged that there’s sexism in the music industry, and perhaps its sting is most felt in that some of the nation’s founding female rockers are women who remain largely uncelebrated. Some artists fault the media for their lack of visibility; according to a 2012 report from the Women’s Media Center titled The Status of Women in the U.S. Media, “women have consistently been underrepresented in occupations that determine the content of news and entertainment media, with little change in proportions over time.”

Given the Valley’s two prominent women’s colleges and the longstanding local emphasis on gender issues, it can appear from the outset that Western Mass is pleasantly insulated from the sexism that breeds the neglect of such rock stars. June Millington, however — who founded the first big-time all-female band Fanny with her sister Jean in 1964, recorded at The Beatles’ Apple Studio, among other major firsts — lives locally, heads the Institute for the Musical Arts (IMA) in Goshen with partner Ann Hackler, and still had to self-publish an autobiography in order to document her trials and tribulations in the rock industry.

Ideally we’d be able to say that rock and roll has grown away from discrimination since the days when Fanny was criticized in reviews simply for being “girls with guitars,” but Steve Waksman, Professor of Music and American Studies at Smith, says that rock and roll remains largely unchanged as far as sexism is concerned — rock and roll is by cultural definition a male-dominated world.

“There’s no question that rock has been a male identified phenomenon from the start,” Waksman says, listing names like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and more. “But when you look closer into the history you realize there are women involved with that moment.”

And Pearson, a self-taught multi-instrumentalist and student in Smith’s Ada Comstock Program, has been looking closely for over twenty years. Talking with Pearson at The Roost about ’90s rocker chicks, my feet tap along to the Fiona Apple and Gwen Stefani playing overhead.

For Pearson, it’s infuriating to see artists like Millington aging among us and still lacking the recognition they deserve.

“People will say, ‘Doesn’t she run that girls rock camp?’” says Pearson. “And I’m like yeah, and she also played in Fanny and recorded “Hey Bulldog” with the Beatles. There’s so much more to say.”

On a frigid January day, wind whips snow into swirling funnels just outside the windows of the IMA barn where Millington, Pearson, and their upcoming gig mates rehearse for a Feb. 5 gig sponsored by Women of Rock. They’ve never played with Millington before. Here, the normal gender roles are reversed — bassist Jason Layne is the only male musician in the room and he takes the supporting instrument typically reserved for the females, while Catherine Capozzi and Mora Precarious take up guitar and drums.

There’s no doubt about who’s in charge. Millington, 67, stands facing the others, seeming to use the neck of her electric guitar as a conducting baton. At first, Layne struggles to stay out of Millington’s way as she sings “turn it up and play like a girl” in the song she wrote by the same name.

“There’s a musical break, there,” Millington says, correcting him. “Let me say those words. It’s like we’re leaving room for the next generation of girls.”

Pearson stands by to fill in parts as needed. Singing with Millington, however, is a challenge for her. “I don’t have a very hard voice,” Pearson tells her when Millington ushers her toward the neighboring microphone.

But Millington has no time for any self-deprecation. “Don’t say that to me,” Millington tells her with a tone that reveals she’s mildly annoyed. “I don’t need your disclaimers.”

Feeling a sense of defeat over Fanny’s inability to make it to superstardom, Millington quit the band in 1973. During the 80s, she started working to nurture musically gifted young women in the way that was never done for her or her sister. In order to change the industry for the better and pass on music to the next generation of women, she and Hackler started IMA in 1986. Still, “nobody believed in an institute for girls and music,” and so it was difficult to start the non-profit.

As Millington leads the practice, she throws her whole body into every note. Her wall of long, silver hair thrashes wildly, revealing her face only in brief moments.

“I sweated through my shirt!” Millington says post-rehearsal, shaking out her clothing. “That’s good!”

After wrapping up the rehearsal, Millington walks over toward the homestead, ushering me along. She grabs a log from the outside stack, nods towards my free hand, and I do the same. I sit with her as she quickly builds a roaring fire in her living room fireplace.

Millington laments the lack of seriousness with which people in the media took her talent. “They were always asking me the same question: What’s it like to be a female musician?” Being a woman in rock and roll means always striving to be better than the rest, she says, and you have to be strong. “Being fabulous enough for people to notice me is a full time job,” she says, smiling.

The autobiography was apparently fabulous enough to inspire Laudable Productions and the Northampton Arts Council to go in on a tribute to Millington at the Academy of Music on Feb. 21.

Millington describes her career’s trajectory as slow yet always moving forward. “Will it peak before I die?” she asks herself aloud. “I don’t know. But I’m still here, and there’s kind of a sweet vengeance in that.”

Pearson hasn’t interviewed Millington for the project yet, but she has her on the list. Completed histories include those of Lydia Lunch, JD Samson, and Alice Bag. Over the past year, Pearson has spent about 50 hours talking with women about their lives and about their rock music.

Julia Cafritz says she talked Pearson’s “ear off” during a dawn-to-dusk interview in her Florence living room. Now 50, Cafritz got started in music at 19 after dropping out of Brown. She had never picked up a guitar before, but that didn’t stop her from bragging to a friend about how she would do it better if she were in a band. That friend took her up on her words and asked her to help form the band Pussy Galore in 1985. She’s perhaps better known for playing in Free Kitten with Kim Gordon.

Harkening to Millington’s bitterness over squandered media opportunities, Cafritz talks about having never been asked questions like the ones Pearson brought.

“I never get asked about my equipment, what guitar, what amp I play through — I guess [interviewers] frankly don’t think about it,” says Cafritz. “While she was interviewing me I was so happy to be part of that project because she was going into a level of depth I think female musicians in general don’t get.”

Waksman explains that, given how culturally weird we are about women and tools — particularly tools that involve technology — it’s easy to see how women playing electric guitars can be marginalized.

“We tend to associate a certain type of expertise more with masculinity than with femininity,” says Waksman. “ Singing is something that’s been more open to female artists because even though it requires a lot of talent, it’s also something that comes more directly from the body, and somehow we’re more comfortable with women having a natural talent as opposed to one that involves mastering a tool or a skill.”

Cafritz joined Pussy Galore more than twenty years after Millington started Fanny, but it seems the same old sexism had not softened, but rather become an industry standard.

“Every time we went to sound check, the sound person would pull my guitar out of the mix or pull it so way down that it was insulting,” says Cafritz. “I would see the same thing happen to Kim Gordon, someone much more famous, all the time.”

Waksman says that from the onset certain expectations were built into the genre and later set into stone.

“We tend to give men in our society more room to break the rules than we do women,” he says. “And rock and roll is a style in which, at least ostensibly, the best artists are rule breakers.”

For Pearson, all of the coordinating, interviewing, and editing has meant there’s no time for paid work. Still, you’ll see her putting on shows sponsored by the Women of Rock Oral History Project, like one featuring guitarist Ava Mendoza this Saturday at the 13th Floor in Florence. It doesn’t mean the college is helping to pay for the shows, which highlight the same iconic female rockers Pearson hopes to recognize through the project. It just means Pearson is donating time, effort, and any equipment she has in order to see these women acknowledged.

“I feel a sense of duty to help preserve these women’s legacies,” says Pearson, adding that it’s important for rising artists to know their predecessors. “I grew up loving them and searching for information and never finding it.”

Pearson calls herself a “really successful stalker.” She grew up idolizing these musicians and now she has a Smith College collection to allay fears she’s just a “crazy person waiting in line.” Pearson says she asks the artists about things she wanted to know growing up. “I’ve always been really nosy,” she says.

That insider’s perspective, says Kelly Anderson — an oral historian at Smith College who helped Pearson on the independent study that inspired the project — is key. “She was able to successfully invite so many of those musicians in because she already had their trust,” says Anderson. “I think otherwise they might have just have perceived her as another journalist.”

Pearson doesn’t get downtrodden if she’s ignored or rebuffed in her attempts to reach artists. She refuses to take Courtney Love off her list despite being rejected by Love’s publicist. “I’ll get her,” Pearson says with a determined nod of the head, adding that she’ll wait until she graduates this spring before she does any more interviewing.

The college’s American Studies department, she says, has pitched in with some travel funds — Pearson has had to travel as far as Los Angeles to ensure the oral histories are taken in person.

“I would do this all day every day,” Pearson says of her work as a women of rock documentarian, even though the “terrible typist” describes transcribing as “the bane of my existence.”

Anderson says all the work is worth it as it gives these artists a chance to tell their stories in an entirely new way. “It’s a dialogue, really, so it’s a different kind of evidence in a way,” Anderson says. “It has the potential to get people off their script and it’s an opportunity to raise different questions.”

In organizing her to-interview list, Pearson continues to prioritize women who rocked out during the ’60s and ’70s simply because she fears they’ll die before ever getting to share their stories. “There’s a lot of catching up to do,” she says.•

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com