Here’s one thing the two very different Tennessee Williams plays now running in the Berkshires have in common: The sets have no walls.

In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, on the Berkshire Theatre Group’s Stockbridge mainstage, four white-and-pastel pillars frame the sparsely but luxuriously furnished bedroom of Maggie the Cat and her impotent, alcoholic husband Brick.

It’s a claustrophobic room, full of tension and resentment, but the invisible walls of Jason Sherwood’s set make it feel open to the air and the ears of everyone in Big Daddy’s Mississippi Delta mansion.  Across the back and side of the stage runs an narrow outdoor panorama of truncated treetops and grasses beneath a sunset sky.

Across the back and side of the stage runs an narrow outdoor panorama of truncated treetops and grasses beneath a sunset sky.

The bedroom is the prickly epicenter of uncertainty over which of Big Daddy’s sons will inherit the plantation, “28,000 acres of the richest land this side of the Valley Nile” – Brick, who’s his father’s favorite but too deep in self-loathing to care, or sober, boring Gooper, whose trump card is his children: five potential future heirs, in contrast to Maggie and Brick’s barren marriage.

In The Rose Tattoo, at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Mark Wendland has created the suggestion of a ramshackle house on a Gulf Coast beach: an open platform giving onto a couple of teetering partitions, overhung with a latticework of telephone wires and a towering palm. Behind it, beyond a veritable forest of pink flamingos, stretches a moving panorama of lapping surf, the work of projection designer Lucy MacKinnon, with a sky that slowly changes tone and color with the time of day.

This open-air house is anything but claustrophobic. It’s an organic part of Serafina Delle Rose’s community, a loud, bustling enclave of Italian immigrants on the Louisiana coast. When her beloved (and sexy) husband is killed, the whole community hears her wails and shares her sorrow; and when she suddenly reawakens to the touch and smell of a man (cute and funny Christopher Abbott) everyone can see and hear it. The setting includes the audience, too, as a narrow boardwalk leading to Serafina’s house bisects the seating.

Here’s another thing Tattoo and Cat have in common. Like all of Williams’ plays, they are symphonies of language, played in the most impassioned keys. Marisa Tomei’s high-octane Serafina throws herself into mourning as extravagantly as she later liberates her pent-up sexual passions. And in Rebecca Brooksher’s kaleidoscopic performance, Maggie’s rants and taunts and complaints to Brick are glib, devious streams of thought that keep her from screaming or going mad: dancing on a hot tin roof as long as she can stand it. And yes, both plays are crucially about sexual longing.

And one more: the kids. In both plays, the drama is regularly interrupted by unruly children, but to quite different effect. In BTG’s Cat, Gooper’s five “no-neck monsters,” as Maggie calls them, are represented by just one eavesdropping, cap-gun-slinging girl (Julianna Salinovici), exploding moments of tension or tenderness. In WTF’s Tattoo, three urchins scamper noisily in and out, adding to the atmosphere of lively hubbub. (And speaking of kids, a live goat has a couple of walk-ons.)

Here’s where the two shows differ. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is one of Williams’ “big” plays, on a par with A Streetcar Named Desire and The Glass Menagerie, all of them anguished studies of regret, discontent, self-deception and lies (the leitmotif word in Cat is “mendacity”). Themes of homosexuality – hidden, guilt-ridden, castigated – wind through all three of these and more in Williams’ work.

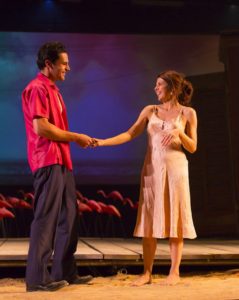

The Rose Tattoo, by contrast, is a comedy, and an exuberantly heterosexual one to boot. In Trip Cullman’s wonderfully steamy but sometimes overheated production, Tomei’s Serafina is so profusely horny that she’s, well, like a cat in heat on a hot tin roof, though sometimes her ardent physicality becomes a bit clownish. Serafina’s teenage daughter Rose and her sailor boyfriend (a radiant Gus Birney and a sweet Will Pullen) likewise feel the insistent pull of needy hormones in virgin bodies. The play’s near-operatic passions are further enriched by Lindsay Mendez, who gives glorious voice to Italian folksongs during transitions.

The Rose Tattoo, by contrast, is a comedy, and an exuberantly heterosexual one to boot. In Trip Cullman’s wonderfully steamy but sometimes overheated production, Tomei’s Serafina is so profusely horny that she’s, well, like a cat in heat on a hot tin roof, though sometimes her ardent physicality becomes a bit clownish. Serafina’s teenage daughter Rose and her sailor boyfriend (a radiant Gus Birney and a sweet Will Pullen) likewise feel the insistent pull of needy hormones in virgin bodies. The play’s near-operatic passions are further enriched by Lindsay Mendez, who gives glorious voice to Italian folksongs during transitions.

In David Auburn’s sensitive staging of Cat, Brooksher’s enthralling performance is augmented by a strong supporting cast: Michael Raymond-James, a surly but aching Brick; Linda Gehringer, poignantly exasperating as fussy Big Mama; Jenn Harris as Gooper’s vampiric wife Mae; Festival favorite David Adkins in a tipsy cameo; and above all Jim Beaver, alternately gruff, rude, vulgar, nostalgic, querulous and volcanic as Big Daddy.

For me, seeing these two plays back to back last week was a reminder of Tennessee Williams’ dramatic and verbal power, and of the enormous heart that suffused all his work. A recommended two-fer, but hurry: Both of them close this weekend.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof photos by Emma K. Rothenberg-Ware

The Rose Tattoo photos: T. Charles Erickson and Daniel Rader

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com