Decades later and General Electric still hasn’t remedied its contamination of the Housatonic.

Woods Pond in Lenox is the picture of quaint backwoods New England: the kind of place leaf-peepers flock annually to the Berkshires to behold. The golden yellows and fiery oranges of the remaining foliage pop from the gray sky and cast their reflection on the water’s surface, but beneath the tranquil veneer lies a hidden danger:

This pond has one of the highest concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyl, better known as PCBs, in the Housatonic River, a waterway that was polluted by the suspected cancer-causing agent for decades.

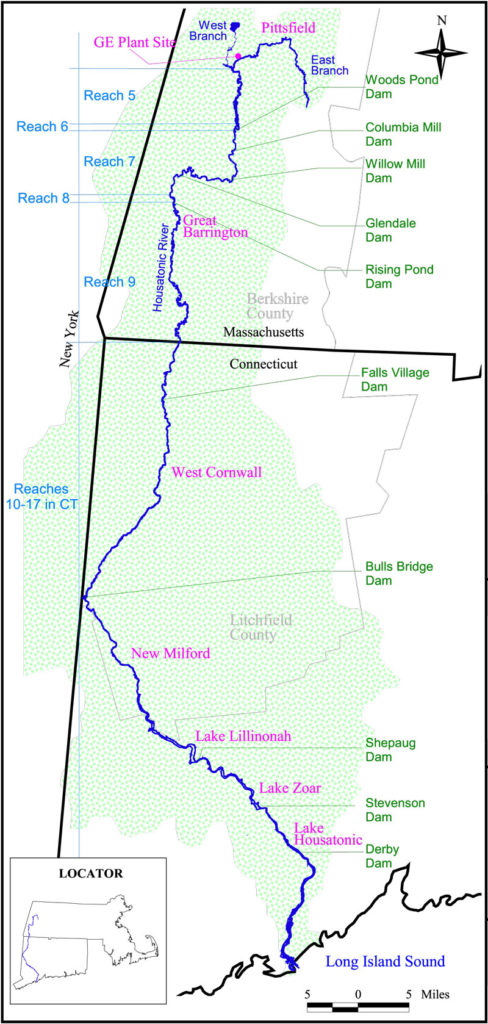

The chemicals — shown to be toxic to humans and banned as probable human carcinogens by the federal Environmental Protection Agency — were used by General Electric from about 1932 to 1977 in the manufacture of electrical transformers at their Pittsfield plant. During that time, the EPA estimates that GE dumped between 100,000 and 600,000 pounds of PCBs into the Housatonic, traces of which can now be found all the way down to the Long Island Sound. PCBs can persist in the environment for hundreds of years, and the EPA ruled in 1991 that GE was on the hook for cleaning up its mess.

The company cleaned up the the first two miles of the Housatonic downstream from the Pittsfield plant, dredging nearly 110,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil from the river between 1999 and 2011. An additional 15,815 cubic yards (20,580 tons) was dredged from the nearby Silver Lake site in subsequent years, and 158,000 more was removed from 19 off-site areas.

And GE still has a lot more work to do, according to both activists and the EPA — but just how much work depends on who you ask.

In late October, the EPA issued the long-awaited final permit modification, which allows GE to begin remediation efforts on the Rest of River project. It largely ignored GE’s opposition to aspects of the plan, most notably the stipulation that GE transport the contaminated material to licensed out-of-state waste facilities. GE favors a plan to create a local disposal site instead — a move that’s left local governments and activists up in arms.

GE has gone as far as to purchase or lease land for three potential disposal sites close to the river in Lee, Lenox, and Great Barrington — including a parcel near Woods Pond — despite condemnation from the community and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection on the grounds that the creation of a PCB dump would not only violate state law, but would not do enough to ensure that those same PCBs don’t leach back into the groundwater.

The six most affected towns — Lenox, Lee, Stockbridge, Great Barrington, and Sheffield — have formed the Housatonic Rest of River Municipal Committee to ensure that the towns are legal interests are represented during the cleanup. Nat Karns is the director of the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission, which coordinates and advises the committee.

“Under the cleanup, GE’s being allowed to leave a whole lot of PCBs behind,” says Karns. “They’re not being required to clean up all of the area to what really is the scientific standard. They’re getting away with murder anyway. They shouldn’t be allowed to then create a landfill on top of that.”

“GE will clean the Housatonic Rest of River,” GE spokesperson Susan Bishop wrote in a statement following the release of the final permit. “The only question is how it will be cleaned. We remain committed to a common-sense solution — supported by fact, science and law — for the Housatonic Rest of River that protects human health and the environment, does not result in unnecessary destruction of the surrounding habitat, and is cost effective. We are currently reviewing the EPA’s final decision and look forward to resolving its shortcomings.”

A GE statement out in March says out-of-state transportation of contaminated soil would add another $200 to $300 million to the cleanup. The total cost of the15-year project is expected to top $613 million. The statement also criticizes the EPA plan as ecologically unsound in the amount of dredging it requires the company to perform and has promised to appeal to the EPA Environmental Appeals Board. At the time the Advocate went to press, GE had not yet submitted its appeal of the final decision and company officials declined to answer questions about the details of remediation.

Advocates say GE’s appeal is one in a long line of delay tactics meant to stall the cleanup.

“It’s GE basically wanting to let the stuff sit there for hundreds of years [and] let nature take its course,” says Nat Karns. “Don’t worry that the ducks aren’t edible and the fish aren’t edible and that the ecosystem is harmed by their PCBs. That’s corporate B.S. And GE is definitely legally permanently responsible for their PCBs.

“And it’s right over a drinking water aquifer,” says Karns, who worries a liner to protect the soil and water from contaminants wouldn’t necessarily last the lifespan of the PCBs.

“Just as GE has made it clear that we’ll all be in court forever, towns on the landfill issue feel the same way,” Karns says.

GE’s challenge to the EPA’s final decision further delays a process that’s been slow-tracked since 1991, but it’s not the only legal hurdle facing the EPA’s plan. The Housatonic River Initiative — a group that advocates for the river’s cleanup — filed an appeal against the EPA plan on Nov. 7 on the grounds that it doesn’t do enough to clean up the river. The appeal was accompanied by a petition with 2,675 signatures demanding that the EPA investigate more natural remediation options, block efforts by GE to dispose of PCBs locally, and to make GE remove over 94,000 pounds of PCBs instead of the 47,000 pounds the EPA plan currently requires.

Tim Gray is the group’s executive director and has been fighting to get the river cleaned up since the beginning.

“We think that EPA has really fell short of doing their job under the Clean Water Act,” Gray says. “That law calls for a swimmable, fishable river someday. And we know the cleanup that’s proposed right now will not give us that when they’re done cleaning up and they say we have to wait another 30, 50 years before fish will start to be edible.”

One thing that Gray and GE seem to agree on is that the first phase of the cleanup — the two miles of the river immediately downstream of the Pittsfield plant that GE restored — was a resounding success. He says that this pokes holes in GE’s assertion that the dredging called for in the Rest of River plan is too ecologically invasive.

“There’s a vibrant plant and tree community growing in these two miles to where now you go back and look at it, you can’t even tell that it was dredged a number of years ago,” Gray says. “If you study it, you find out that that 2-miles stretch was a success story that GE can dredge a river, they can clean it up, and then you can restore it… but their rhetoric says leave us alone, we don’t think we should have to clean up our mess.”

In 2014, a GE report showed that levels of PCBs found in fish in the Housatonic River in Connecticut were higher than at any point in the past decade. The cause of the spike remains unknown, but Gray thinks it’s possible that the breach of a dam in Pittsfield in the preceding years or the stirring sediments by storms might be a factor.

“It shows you that these PCBs are active,” he says.

EPA spokesperson Jim Murphy says that GE is utilizing all the legal options laid out under their original agreement with the EPA.

“Getting to the decisions has often taken more time than people would like to see,” Murphy says. “They have their positions, and unfortunately that’s the process. There’s dispute resolution options for them and they often take advantage of those, so it’s not surprising. The basic thing is that once we finally get to a cleanup decision, we usually work very well together.”

Murphy also says that EPA has adequately explored bioremediation solutions.

“We’re pretty convinced that there’s nothing out there at the moment that would be appropriate for this work,” Murphy says.

Meanwhile, the impact PCBs are having on residents in the area is hard to discern in the absence of long-term studies. While certain types of cancer have spiked in the Pittsfield area in recent years, the rise has not been definitively tied to PCB exposure.

Laura Vandenberg is an assistant professor and director of the Environmental Health Sciences program at UMass.

Vandenburg says that part of the reason that PCBs are so harmful is that they accumulate in the body, especially in fatty tissues and breast milk.

“There’s a sort of very cynical saying for women that the best way to get these chemicals out of your body is to breastfeed,” Vandenberg says. “Exposure to PCBs alters the function of thyroid hormones. In adults, thyroid hormone is important for things like maintaining body weight and maintaining body temperature, but for fetuses and children, thyroid hormone is essential for brain development.”

They’ve also been shown to cause cancer in lab animals, she says. The EPA and other regulatory bodies consider PCBs probable human carcinogens, she says, because of the absence of human trials. She, like many other toxicologists she knows, is reasonably convinced that the chemicals cause cancer in humans.

“I think sometimes people think oh, that’s banned so we don’t have to keep talking about it, we don’t have to keep worrying about it, we’ve done our job,” she says. “For chemicals like that, it’s not true. We’re going to be stuck with these things for a couple more generations, which means we’re going to be stuck with their health effects.”

EPA officials have argued that the stiff wave of local resistance to the local landfills will make efforts to implement them unreasonable, and that it would be “highly unusual” to do so in the face of such local opposition anyway.

During the initial phase of the project, GE was allowed to dispose of PCBs on-site at the Pittsfield plant — the now-infamous Hill 78 site — about 400 feet from Allendale Elementary School. The site is now capped on top, but not beneath. A monitoring program is currently in place to watch for groundwater contamination. PCBs have been shown to vaporize and the EPA conducts air sampling in the vicinity of the plant. The EPA has not detected substantial PCB levels in the air since 1994, when “elevated levels” were documented in the vicinity of Silver Lake.

People in the area are still wary of using the river.

“PCBs in ducks tested so high that you could consider them hazardous waste,” says Tim Hickey, an environmental science instructor at Berkshire Community College and lifelong Lee resident.

Hickey was at Arcadian Shop, an outdoor outfitter in Lenox, to have some work done to his kayak last month. He takes his students out paddling on the river in order to teach them how to perform basic analyses and make water quality assessments, asking them to assess the feasibility of a program to reintroduce salmon into the river. But, he says, eating any of those hypothetical salmon would be out of the question because of the PCB contamination. He’s angry with GE for what he says is “corporate negligence,” he’s joining others who say that the company has known about the threat posed by PCBs since the 1930s.

GE argues that local objections to the disposal sites are not legally relevant and have sought to dismiss them from legal consideration, according to EPA statements, but the EPA’s regional legal counsel Carl Dierker found that considering the concerns of residents was reasonable.

Dierker released a statement just before the final decision, in which he wrote: “EPA here has come to the conclusion that the long-standing and vigorous opposition to a new PCB landfill by state and local stakeholders … effectively means that a certain path forward (i.e., on-site disposal) would be difficult or impossible to pursue, and thus would not be implementable. … Moreover, it would be highly unusual for any major RCRA [Resource Conservation and Recovery Act] or Superfund cleanup plan to be selected and implemented by EPA in the face of strong state opposition.”

GE argued in a January 2016 position paper that not only should it be allowed to create the landfills locally — because it argues that EPA acknowledged that transporting material to licensed out-of-state facilities is no more safe than creating local ones — but that it should have to remove only 44,000 cubic yards of material from Woods Pond before capping it, not the 340,000 yards the EPA had set forward. Why? Because the company asserts that EPA’s own models showed no discernable difference. Additionally, GE suggested that the now-infamous Hill 78 and Building 71 “on-plant consolidation areas” — permitted under the 2000 agreement — offer legal precedent for local disposal sites.

“EPA asserts that on-site disposal would be difficult to implement,” writes Ann R. Klee, GE’s vice president of Global Operations for Environment, Health & Safety in the March statement. “It is incontrovertible that on-site disposal is EPA’s ‘presumptive remedy’ for the disposal of PCB-contaminated sediment and soil, which it has approved and implemented at many other sites across the United States, including in Pittsfield and other locations in Massachusetts.”

Gray worries, too, that GE could still get its way on the local PCB dumps.

“Hill 78, which is where they dumped it is this huge PCB dump that goes up about 45 feet in the air and there’s about 4 to 5 acres of PCBs right next to an elementary school. That’s a precedent that was set in the first consent decree,” Gray says. “We think in the end that if it gets before a judge and there’s precedent there that the powerful GE lawyers — which they are — might be able to win against the EPA. But he EPA promises us what they say — and the state of Massachusetts is part of that promise, too — they have been ‘no dump’ in their orders. But do they have the guts, the money, everything they need to fight GE in the courts in Boston?”

Peter Vancini can be reached at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.