Two world premieres kick off the season at Williamstown Theatre Festival, one a raucous comedy, the other a brief, intimate tragedy. The Closet holds forth on WTF’s Main Stage through July 14th, while The Sound Inside plays through the 8th on the smaller Nikos Stage. Both feature bona fide stars in roles that fit them well.

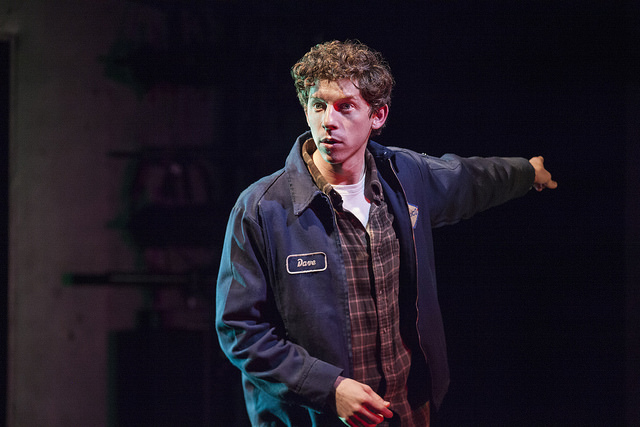

Adam Rapp’s The Sound Inside, unfolding over an intermissionless 90 minutes, is is a rather bleak two-hander that circles around a pair of lives rooted in words. Bella (Mary-Louise Parker) is a Yale professor teaching a course called Reading Fiction for Craft. The key text is Crime and Punishment. She published a novel years ago and seems to be having trouble pulling the next one out. Christopher (Will Hochman) is one of her students, an intense freshman working on his own first novel. He narrates it to her piecemeal, evoking the 19th-century practice of publishing novels in installments.

On one level, the play is about the human connections – and disconnections – it uncovers. But mostly it’s about literature. Much of the talk revolves around books, and not just the story but the style and structure are shaped by literary conventions.

On one level, the play is about the human connections – and disconnections – it uncovers. But mostly it’s about literature. Much of the talk revolves around books, and not just the story but the style and structure are shaped by literary conventions.

Bella begins in a spotlight, speaking to us as if she were describing someone else speaking about us: “A middle-aged professor … stands before an audience of strangers. She can’t quite see them but they’re out there.” After a while she shifts into the first person, but never abandons the narrative stance, objective and dispassionate, even when revealing she has cancer, having sex with a bar pickup, or pondering suicide.

When Christopher bursts into her office, half the dialogue is paraphrased in asides: “I ask him if he’s happy with his prose. He says he’s not even thinking about it.” She’s narrating her own life like a novel written in the first person.

Alexander Woodward’s set accentuates the play’s themes of distance and alienation. Bella’s office is a cramped, featureless box pushed to the back of the empty stage. Darkness surrounds everything, and Heather Gilbert’s lighting is sparing with the wattage.

Parker’s Bella, in big professorial glasses, is sardonic, ironic, opaque, and virtually emotionless. We get barely a smile from her and rarely a departure from the impassive tone of voice. This makes Christopher the more interesting character, and Hochman’s performance the more engaging. He’s awkward and naïve, opinionated and volatile, obsessed by the sound inside himself that drives his writing – the voice that eludes Bella.

Parker’s Bella, in big professorial glasses, is sardonic, ironic, opaque, and virtually emotionless. We get barely a smile from her and rarely a departure from the impassive tone of voice. This makes Christopher the more interesting character, and Hochman’s performance the more engaging. He’s awkward and naïve, opinionated and volatile, obsessed by the sound inside himself that drives his writing – the voice that eludes Bella.

Both of them are loners, isolated and disaffected, like Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov (and an impulsive, senseless murder figures here, too). David Cromer, who won a Tony this year for directing The Band’s Visit, guides the intersecting trajectories with a sure hand that helps to boost the piece beyond its literary conceits.

Coming Out

If the Nikos Stage is skeletally bare, Allen Moyer’s set for The Closet more than makes up for it. Douglas Carter Beane’s comedy takes place in the shipping office of the Good Shepherd Catholic Supply Warehouse in Scranton, PA, its back wall an Everest of shelves stacked with parochial paraphernalia – candles, chalices, plaster figurines – while three cluttered desks crowd the floor.

Based on Francis Veber’s play and film of the same name (Le Placard in French), it’s a classic farce, provoked by a misunderstanding (in this case, intentional) that gets out of control and leads to confusion, frantic action, and a panicked first-act curtain.

Based on Francis Veber’s play and film of the same name (Le Placard in French), it’s a classic farce, provoked by a misunderstanding (in this case, intentional) that gets out of control and leads to confusion, frantic action, and a panicked first-act curtain.

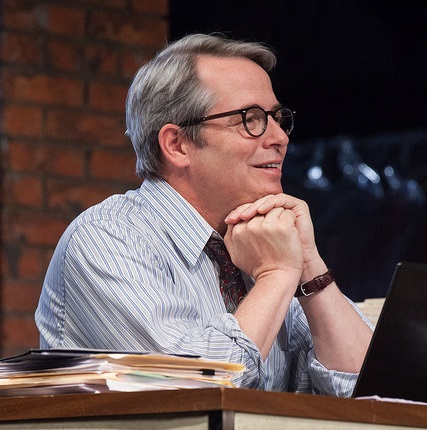

Martin (Matthew Broderick) is a colorless desk jockey in the warehouse, resigned to his shitty life – his wife has divorced him, his son hates him – and to the likelihood that he’s about to be fired from his shitty job. He has decided to rent out one floor of his sprawling old house, a move made in resignation, but which proves to be his salvation.

His new tenant, the extravagantly gay Ronnie, recognizes that in this age of minority rights, the company won’t dare fire Martin if he’s part of a protected group – a homosexual, for example. A kind of fairy godfather, strewing joy and chaos, he starts a rumor that quickly spreads to everyone in the office and then goes viral.

The comedy feeds off the notion that in today’s (somewhat) more tolerant culture, it’s not only okay to be “different,” it’s cool. Martin’s estranged teenage son suddenly admires his father’s apparent bravery in coming out. His relentlessly perky officemate Brenda (Ann Harada) is delighted and starts belting out show tunes for Martin’s bewildered benefit. His boss, Roland (Will Cobbs), finds that the “news” kindles a faint stirring of his own.

The comedy feeds off the notion that in today’s (somewhat) more tolerant culture, it’s not only okay to be “different,” it’s cool. Martin’s estranged teenage son suddenly admires his father’s apparent bravery in coming out. His relentlessly perky officemate Brenda (Ann Harada) is delighted and starts belting out show tunes for Martin’s bewildered benefit. His boss, Roland (Will Cobbs), finds that the “news” kindles a faint stirring of his own.

The seamless ensemble, under Mark Brokaw’s spirited direction, are hilarious and perfectly cast. As Ronnie, Brooks Ashmanskas, owner of a complete vocabulary of camp moves and mannerisms, employs them all, shall we say, fabulously. Broderick is the marquee name, but he mostly plays, um, straight man to the others’ quirkier characters. He does it amusingly and affectingly, at first baffled, then embracing the subterfuge with a dorky enthusiasm, learning to “act gay” under Ronnie’s flamboyant tutelage.

Act One is clockwork-tight, first introducing the premise then spinning out its complications and consequences. After the intermission, the playwright runs into the dreaded “second act problem” – how to maintain the momentum and amp up the situation. With such a delicious hypothesis, the play needs and deserves more comic snags and a more explosive payoff. Aside from a couple of predictable twists, the second half is mostly a series of comings-out of various kinds, as everyone ventures out of their own hiding places.

Act One is clockwork-tight, first introducing the premise then spinning out its complications and consequences. After the intermission, the playwright runs into the dreaded “second act problem” – how to maintain the momentum and amp up the situation. With such a delicious hypothesis, the play needs and deserves more comic snags and a more explosive payoff. Aside from a couple of predictable twists, the second half is mostly a series of comings-out of various kinds, as everyone ventures out of their own hiding places.

Which is the playwright’s larger purpose – to suggest that we all may have our own “closets” where we hide from our true selves. Despite the soft landing, though, in this Closet the laughs far outweigh the lessons.

Photos by Carolyn Brown

Chris Rohmann is at StageStruck@crocker.com and valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann