My Pal George

Written and performed by Rick Cleveland; directed by Eric Simonson. Through July 21, Berkshire Theatre Festival (Unicorn Theatre), Main Street, Stockbridge, (413) 298-5576.

Two summers ago, Rick Cleveland sat at a center-stage table in the Berkshire Theatre Festival's intimate Unicorn Theatre and read the script of his one-man show, My Buddy Bill, to a wildly receptive audience. It was a humorous account of his brief friendship with Bill Clinton and the presidential dog, Buddy. This year he's brought its sequel back for a trial run.

My Pal George plays at BTF through this weekend. It recounts, with the tongue even deeper in the cheek, Cleveland's attempts to potty-train the current president's Scottish terrier, Barney, who has, as Dubya puts it, "a urinification problem."

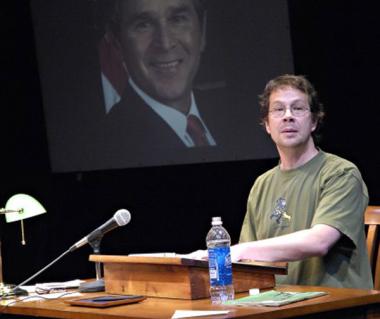

Cleveland, a soft-spoken, unassuming man, is primarily a television writer, most recently for Six Feet Under and before that for The West Wing. His delivery is deadpan, and his vocal caricatures of Bush and Cheney are minimal but effective. Seated again, with script in hand, he is backed by a huge reproduction of the iconic painting "Washington Crossing the Delaware." The heroic imagery is riddled with historical inaccuracies, and serves as an appropriate metaphor for both this fictionalized memoir and the Bush presidency: an exercise in deception for, respectively, aesthetic and political purposes.

After a performance last week, Cleveland reflected on the art, craft and pitfalls of political comedy.

Advocate: Though it's told like a true story, and is based on real incidents, it's pretty clear that a lot of your narrative is made up. Where do you draw the line between truth and fiction?

Cleveland: Spalding Gray was a mentor of mine, and it was amazing to me how much fiction and embellishment there was in his pieces. Then I started reading a lot of Mark Twain and I realized he used to do this, too. He would speak extemporaneously, and if there was a famous person in the audience he might include them in a tall tale. It's like an illusion. You use your own name and tell a story. But I always figure that people at some point realize that it's a shaggy dog story—no pun intended. Hopefully they enjoy it and I get to sneak in some trenchant political observations, and that's even better.

Have you found your observations too trenchant for some people?

When Comedy Central made me the offer to do My Buddy Bill as a special, we started looking for a theater. I had a relationship with the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, and [Artistic Director] Bob Falls said, "Well, you can do it, but you can't make the George Bush joke you've got at the end. It makes it too overtly political." And I was like, "Well, it is overtly political, disguised as a comedy." Then somebody told me, "You know, they have board members and subscribers who are Republicans."

When I left graduate school in 1995 I thought, "I'm never going to write for television, because only on the stage can you say anything." And now, at least in this instance, it's reversed. You can now say anything you want on television—on HBO or Comedy Central, anyway.

What about BTF's audience? There must be Republicans in it.

Well, this is Western Massachusetts, and I think it's pretty diehard liberal Democrat. One person said to me on opening night, "You should draw more blood!" That was the one criticism I got. Plus, I think the zeitgeist now, it's no longer a minority that are calling [Iraq] a quagmire, we have Republicans that are going over to the other side one after the other. It's not rats off a ship yet, but it's going to get there, certainly before the next election.

You ended up doing the Comedy Central shoot at the 92nd Street Y in New York. Did you think that audience might take offense at the cracks you make about the Clintons?

I was worried they were going to kill me, because—well, I don't really bash Hillary, but I do take a few shots at her. And the more I went after Hillary they not only laughed, but they stood up and gave me ovations after every Hillary joke. I don't know what that tells you about the Upper East Side of New York, but it doesn't sound good.

Are you doing revisions of My Pal George while you're performing it here?

I'm changing it almost every night. I put in a bit about Mitt Romney driving to Canada with his dog strapped to the roof of his car, then took it out, then put it back in tonight. I'm still feeling it out. Also cutting. It runs 75 minutes. I think that's a good length. Nobody has to go to the bathroom. I worked at Second City, and—this is a crude phrase, but as [Second City "guru"] Del Close used say, "Fart and get offstage." That's what I try and do.

What have you learned from trying it out in front of an audience?

The audience tells you everything. You hear the laughs, you hear when the laughs are a little off, you hear when butts move around in seats, you hear coughing, you hear all these things. I'm a huge Marx Brothers fan. They performed their shows on the road, all over the country, then did them on Broadway, and then went out to Los Angeles and committed them to film. And they are the only comedy act from that era that holds for laughs on film. Groucho said that comedy is math. If you add a wrong syllable, or too few hard consonant sounds in a punchline, it doesn't work. I'm certainly not that caliber of a mathematician, but being here makes it so much more ready to go to the next place.

Are there things you've found that don't work?

There are some things here that aren't working because it's an older audience, but if I hear younger people laughing, I know I'm not going to cut it, because I know where I'm eventually headed. I like to do university one-nights, and I hope Comedy Central will want to do this one too. In the last piece I had a whole section on Billy Bob Thornton. I did it in this theater, and in the Geffen Playhouse in L.A. too. Both places, I could hear people in the audience saying, "Who's Billy Bob Thornton?" And I would go, "All right, but I'm not cutting that—I'm just going to go for a younger audience."