A recent post by Marisa Parham about students’ hesitation to use the “f” word (feminism) struck a chord with me. I have heard this for a decade from students as well as from my peer group (folks in their mid 30s). Since this disavowal of “feminism” seems so severe and pervasive I’ve tried to sort out its genesis. My thoughts go something like this: In an age when film stars and politicians speak about “big” issues like global warming, AIDS, childhood poverty and violence around the world, “feminism” can seem limited and limiting. It can feel self-indulgent and individual, much like the “feminism” invoked in the recent “Mommy Wars." In some ways I don’t blame my fellow Americans who shun not only the politics of feminism but the word itself. After all, where do we see or hear feminism in popular culture or politics? To what greater good is it connected?

For years, as a way to bring feminism back as a viable “ism,” I’ve turned to the history of feminism’s second wave. But while in my earliest days of teaching women’s studies I would highlight the “sisterhood” (a la Robin Morgan) aspect of the era and its relevance in a specific historical moment, more recently I have focused on how second wave feminism can instruct us regarding the important work of social movements broadly. After all, because gender and power are always related, it focuses our attention on the ways in which social justice work requires gender analysis.

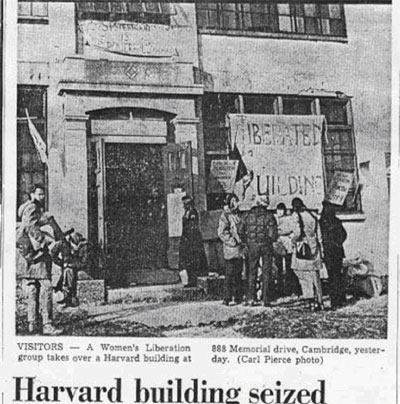

“This is a Liberated Building” (image from March 1971 takeover)

The impetus for this shift was stumbling across a wonderful case study: the little-known takeover of 888 Memorial Drive in Cambridge, MA (a Harvard-owned building) by Boston-area feminist activists in 1971. The event led to the establishment of the Cambridge Women’s Center, and the story it tells about second wave feminism may be my best argument yet for why we should all shout “feminism” from the mountaintop. Why? Because the event’s contours offer a rich set of lessons for both those who would dismiss “feminism” out of hand and those who hope to learn from its second wave. What follows are some takeover highlights and a lesson each one might offer to those looking for a “usable second wave” amidst skepticism and cynicism of our supposedly “post-feminist” age.

“Not Chicks” from CWLU Herstory Website Gallery

The 888 Takeover: HIGHLIGHTS AND LESSONS

Highlight #1: The Personal was Political – but not in a simple, singular way.

The Cambridge Women’s Center was born out a ten day takeover of a Harvard-owned building by Boston area women on International Women’s Day, 1971. The event was organized by members of the socialist feminist group Bread and Roses to highlight the need for a women’s center as well as raise awareness of Harvard’s poor treatment of women and residents of the working class and minority area of Cambridge called Riverside. But the March 6 date spoke to another takeover goal: linking the plight and needs of women in the Boston area with a very broad (and related) social agenda that included anti-war and anti-imperialist activities, anti-corporate activism and race and class-based concerns across the world.

Lesson #1: The personal CAN be political if you think big.

The women who spearheaded the takeover of 888 saw themselves as part of a much larger social and political struggle and acted on that. The personal (their experiences as women in a male-centered society) might have been political but takeover organizers saw the implications of the personal in very broad terms, linked to big, global issues. In some ways, because gender-based activism is so very much about highlighting power differentials, gender as a category of analysis becomes even more powerful when linked to broadly to challenging the status quo.

Highlight #2: 1971 came to the Women’s Movement

Despite the many potential unifying forces at play in the Harvard takeover, what became obvious early on in the event was that the notion of a united “sisterhood” was being challenged by participant worries over whose issues/needs were most pressing and who had the power to speak for the “group.” There were arguments over such things as displays of affection between women, whether to negotiate with Harvard or not and the extent to which the Riverside concerns could or should remain part of the professed conditions of evacuation. Although women of all colors, educational levels, sexual orientation and marital and employment status, spent time inside 888, discussions (arguments even) raged over what the movement meant to each group and whether all females in the building (or outside) could be part of the era’s “sisterhood”. In many ways this event typified one 1972 statement that “The United States of America” happened to Women’s Liberation in 1971.

Lesson #2: Real people, with multiple markers of identity make up movements and to understand any movement (or if you are thinking of starting your own) it is prudent to recognize this fact at the outset.

The 888 takeover reminds us that no person is defined only by gender. This is not to say that sex (or gender) does not unite, but to me one important area in which the significance of the second wave far outstrips that of the first wave (a.k.a the suffrage era) is the extent to which women of the second wave tried to address and acknowledge diverse needs, experiences and agendas within a supposedly monolithic group called “women.” In large part because of the second wave, no “movement” today can assume a one-size-fits-all approach to its agenda or membership.

Highlight #3: Controlled Discord and Long Term Success

As the ten days wore on women inside 888 struggled to find common ground. But in the end, the takeover was a success because of, not despite, the debates. Discord was controlled enough to get Harvard to take up the issue of Riverside and not attack the building, and the event stirred up enough sympathy from one anonymous supporter to give $5,000 for a Women’s Center. The ten days spawned not only a new institution but a new awareness of the range of groups needed to meet all women’s needs in the Boston area. The tensions of the takeover days encouraged women to strike out on a variety of paths in a quest to meet needs they had felt most pressing—and sometimes un-addressed—inside 888. Following the 888 takeover, women created a host of new community organizations in the Boston area. In Boston, post 888 “feminism” seems to be in direct response to the lament (and challenge) of Robert Salper, feminist critic and female liberation member, speaking in the early 1970s:“A movement that can not learn from its past, that is too insecure and fearful to engage in self-criticism, that is too self -interested to be able to change its direction , too blind to see that all women are NOT sisters— that class exploitation and racism…exist within the women’s movement—becomes a trap, not a means to liberation.”

Lesson #3: Disagreement is necessary for social change/growth.

The 888 takeover offers us a case-in-point for arguing that discord/discontent is the lifeblood of true social change. So often I encounter peers and students who avoid disagreeing with one another. Perhaps they are being polite but my sense is that this reticence is tied more closely to the absence of models of public disagreement leading to positive change. Talk radio, congressional debates, and talking heads of all sorts seem to suggest that debate and argument leads to impasse and polarization. The tensions of the 888 days were real and they were unpleasant at times, but living with the tension allowed new possibilities to emerge. This is a lesson we can all use.

THE PAYOFF: A USABLE SECOND WAVE

So how exactly does this story relate to my peers’ and students’ dismissal of “feminism” today? First, it seems to me that if we can de-mythologize the second-wave by expanding our image of it beyond its most iconic and well-publicized moments to include little-studied events like the 888 takeover the “second wave” becomes a much more usable model for all of us because the movement emerges as something messy and complex with permeable and flexible boundaries. Second, the 888 takeover story offers a way to think about second wave feminism as a model for linking the personal and the political in real, dynamic ways that are constantly shifting and re-forming as new concerns, disconnections and needs arise. Finally, the 888 story is important because the event was intended to link personal concerns with broad social justice issues. Being a woman and being an advocate for women was part of the struggle, but not the end in itself. Advocating for women, reshaping the political geography of Cambridge to include women, and creating tangible markers of women’s presence were all part of a massive strategy to attack and alter numerous social, economic and political hierarchies of a particular time and place. This broader, more global, more holistic view of the second wave is what seems to resonate most with me and it is this image of “second wave feminism” that seems most “usable” for today’s world.

Final Note: In the interest of full disclosure: Recently, it has been my pleasure to serve as a consultant for the 888 Women’s History Project, Inc., (funded by the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities) which is producing a documentary about the 888 takeover. Look for it in a year or so!

“Lipstick and Violence” from CWLU Herstory Website Gallery

— Elizabeth Duclos-Orsello, Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, Salem State College