In the (essentially) one-party city of Northampton, Massachusetts zoning regulations were ratified in September 2006 on behalf of Smith College, an elite private nonprofit corporation with more than one billion dollars in endowments. An issue area known as an Educational Use Overlay Zoning District (EU) was proposed in August 2005 as a key component of a Development Agreement (DA) privately entered into by Northampton Mayor Mary Clare Higgins and Smith College President Carol Christ. Designed without public involvement, the city’s legislative branch was also bypassed and there was no information disseminated through traditional media outlets. Thus the powerless were excluded from the earliest stages of the DA process. The chief executives of the college and the city did not release details of the DA (some of them admittedly positive) until after all of its elements were agreed upon by the two, thus rendering the opinions of impacted but powerless neighborhood residents and others moot.

Smith College

The single element of the DA requiring legislative approval was the proposed EU, which would allow Smith exemptions from various zoning restrictions including local height and building square footage regulations. Smith sought the zoning change because the school had received a $10 million grant from the prestigious Ford Foundation in order to create a new science and engineering complex. The 450,000 square foot complex as proposed is completely out of scale with the abutting neighborhood, which consists mainly of naturally occurring affordable rental housing. (No problem, just remove the neighborhood.)

In seeking municipal approval for the first building, Ford Hall, Smith officials repeatedly asserted their needs to the city for zoning variances or waivers in order to move the project forward in the face of strong neighborhood resistance. Though receiving all of the necessary permits from city boards, Smith officials found the process cumbersome and time consuming and soon thereafter responded by bringing forth the EU proposal, which would streamline future building projects and stymie the issue’s emergence for the powerless. Acting as a local growth machine, Smith plans to increase their land holdings further by purchasing additional properties in the immediate area, removing existing structures and intensifying the use of the land while increasing their capital wealth.

In addressing power Domhoff (1995) outlines the over representation of some groups taking part in important government decision-making. In a city of about 29,000 citizens, Smith employs about 400 Northampton residents, a small fraction. However according to Smith’s website (though since removed), they once had representation on more than eighty local boards and agencies (most but not all Northampton based) revealing the true measure of their power and ability to influence favorable local legislation. Smith is over represented in Northampton politics and committees due to its financial holdings and social prestige.

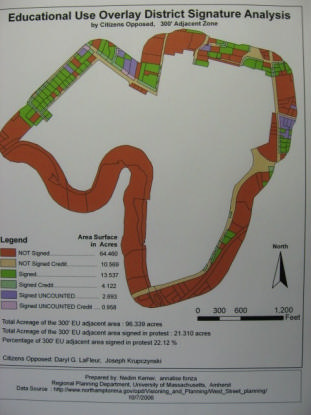

In opposing the EU, abutting or concerned residents (like this one) asserted that the zoning proposal was an infringement on the quality of life of existing residents and a petition was brought forth under the authority of Massachusetts General Law c. 40A, s. 5. The state law indicates that if signatures are presented to the (city) clerk representing owners of 20% of the area of land three hundred feet adjacent to a proposed district prior to final council action, that a three-quarters rather than a two-thirds vote of the entire city council or governing body would be required in order to adopt new zoning regulations or changes to existing ones. In Northampton that means seven of nine councilors would have needed to vote in support of the new zoning rather than six, which is the norm. Two city councilors had recused themselves from the proceedings previously citing conflicts of interest, leaving seven to deliberate. Had the petition been ratified all seven would have needed to vote in favor.

Invalidated properties shown in light purple

More than 44% of property owners abutting the proposed district signed the petition representing 22% of the area of land immediately adjacent. These signatures were submitted prior to final council action as specified by state statute. Though there are no provisions for petition deadlines in MGL c. 40A, s. 5 and the case history for zoning petitions of this nature is mostly nonexistent, Higgins instructed her employees in the planning department, employees who also publicly endorsed the proposed district, to invalidate signatures submitted past a date certain as established by the city clerk. Due to the subordinate relationship of the planning staff to the mayor’s office, opponents argued that utilizing such staff members posed a conflict of interest and that an outside independent authority should be secured in order to certify or decertify the petition. Dismissing this argument and in order to interpret state statutes, the clerk secured the services of the city solicitor, who works for the city at the discretion of the mayor alone. The solicitor expressed an opinion that the arbitrary deadline was legal and this resulted in the invalidation of signatures representing fourteen properties, reducing by 2.6% the 22% of the area of land represented. Now below the 20% threshold, the reduction meant that the two-thirds approval requirement of the city council would be maintained. The final vote was 6-1 in favor of creation of the EU. In this case it appeared the planning staff and city solicitor worked for the mayor personally rather than on behalf of residents, powerless or otherwise.

Upon contacting the state’s Attorney General’s office, petitioners were informed that because the city operates under Massachusetts’ home rule by charter provisions, that any alleged wrong-doing would need to be presented to a judge or jury through civil litigation as brought forth by a person or persons with legal standing. Since the cost estimates for such legal actions were greater than $15,000, the powerless residents did not pursue litigation. In Massachusetts city officials can make decisions, including those of an illegal variety, and if no one chooses to challenge those decisions in court, the decisions stand.

The above activities occurred because planning staff members and the city solicitor, as subordinates to the mayor, are politically expendable in an arrangement similar to the one described by Long (1949 p. 111) regarding the office of the United States president. Northampton’s mayor has charge over 22 of 23 municipal agencies and commissions in a form of government known as strong mayor-weak council. Although the city council must approve mayoral appointments, during the tenure of the current administration the council has failed to reject a single candidate as put forth by Higgins to my knowledge. Thus the mayor has almost monarchical powers that permit her to exclude the powerless from city processes if she chooses.

In this case the powerless but impacted residents were not allowed access to the DA or EU policy processes by a supposedly fragmented government.

Domhoff, William G. 1995. "Who Rules America?" Pp. 324-337 in Theda Skocpol and John Campbell (eds.) American Society of Politics. New York: Macgraw Hill.

Long, Norton. 2005. [1949]. "Power and Administration." Pp. 106-111 in Richard J. Stillman II’s Public Administration: Concepts and Cases. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.