Domenic Sarno knew that plenty of people dismissed his campaign for mayor of Springfield as unwinnable. And he was OK with that, he said. "Nobody gave Deval Patrick a shot in hell of winning," he pointed out to the Advocate in an interview last summer. "If people run me down as an underdog, that's fine."

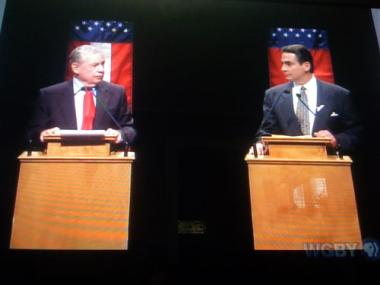

At the time, it seemed like a standard campaign line, the kind of thing a challenger says when faced with a well-established incumbent. Of course, in the end, Sarno had the last laugh (or at least he would, were he not too scrupulously polite to gloat). Last week—in a development that caught-off-guard election-watchers, most notably the local media, alternately describe as "shocking" or "stunning"—Sarno beat two-term incumbent Charlie Ryan by about five percentage points, or 1,100 votes.

While reporters and other self-appointed pundits might have been left scratching our heads over how Sarno pulled off the allegedly undoable, we were not joined by one group within the city: the roughly 11,100 voters who cast their votes for him. And shame on us for forgetting them; after all, in his four terms on the City Council, Sarno has always been an impressive vote-getter, consistently hovering near or landing at the top of the ticket. Still, some questioned whether popularity as a councilor would translate in a mayor's race. Bill Foley has been a steadily popular councilor over the past 20-plus years, but it's hard to imagine him being elected mayor (on second thought, given last week's developments, scratch that).

There are several options for city councilors who want to distinguish themselves from the pack. They can set themselves in direct opposition to the sitting administration, seizing every opportunity to beat up on the incumbent and implying, if not insisting, that they could do a better job (think city councilor Mike Albano, who went on to be elected mayor). They can position themselves as the voice of reason, someone willing to take politically controversial stands because they and their supporters think it's the right thing to do (think former councilor Tim Ryan or current councilor Tim Rooke). Or they can embrace the constituent services part of the job, hitting every civic association meeting; listening intently to, and then following up on, every pothole complaint; always remembering to ask after new babies and ailing parents.

Sarno chose the latter route; the most fulfilling part of his job, he says, is being able to help people out with their problems, big or small. Ask Sarno's supporters—not the would-be political rainmakers but the real, everyday city residents—what they like about him and they will invariably mention his accessibility, his responsiveness. Sarno might be teased for his impeccably slicked-back hair, his gleaming white shirts and gleaming company manners, but to many in the city, he's a local boy made good, a regular guy from humble roots who's done well but hasn't forgotten where he's from. In a proudly working-class city like Springfield, that means a lot.

Perhaps, then, what's really shocking is that voters were willing to give up on Ryan. What Ryan has achieved for Springfield over the past four years has been damned near miraculous: digging the city out of a $41 million deficit and stowing away $17 million in reserves, nudging up Springfield's woeful bond rating and luring private investment back into the city, professionalizing city hall and shutting out the scoundrels who'd been draining it for so long.

Needless to say, Ryan didn't do it alone; much of the progress would have been unachievable without the Finance Control Board imposed by the state in 2004 and the interest-free credit line that came with the board. But that state support, many believe, would not have been forthcoming under another mayor. Given the city's sorry state, state lawmakers were wary about betting on Springfield; Ryan—a well-regarded attorney who also served as Springfield's mayor back in the early '60s—was probably one of the few local leaders who could have inspired enough confidence for them not simply to throw the city into receivership. He had a good working relationship with the Mitt Romney-appointed members of the Control Board, and shares a mutual respect with Gov. Deval Patrick.

Of course, being aligned with the Control Board did not exactly make a mayor a universally beloved figure. As one of two local members on the board, Ryan went into Election Day bearing the burden of every unpopular move made by the board, from its creation of a new trash fee for city residents to its hardline stance with municipal workers during contract negotiations. And his clean-cut reputation did not endear Ryan to some in the city, especially those accustomed to the fast-and-loose days of the Albano administration.

More generally, Ryan has run the city during a remarkably difficult time, and while he did it extremely well—indeed, did much to turn things around—for some voters, he is inextricably linked with this grim time. Many voters, it appears, are eager for these dour days to be over, and they're banking on Sarno to have the energy and optimism to lead the way.

Now, of course, comes the hard part: Sarno's success as a councilor—and, it's clear, much of the enjoyment he gets from that job—derives from his reputation as a likeable guy, a reliable and responsive leader who listens to residents and takes them seriously. And while he says he intends to take that approach with him to the mayor's office, in practical terms, that's going to be tough to pull off. No mayor has the time a councilor does to attend endless community meetings, return endless phone calls from residents.

And as a mayor presiding over a much-improved but still vulnerable city, Sarno will be forced to make unpopular decisions—something his critics say he's been loath to do during his political career. Sarno's detractors say he's avoided taking controversial positions during his time on the Council, instead embracing causes that might be important to residents—noise ordinances, crack-downs on drag racing—but that few would oppose.

Signs from the campaign trail, however, suggest Sarno may not be completely averse to controversy. He's called for the School Committee to replace School Superintendent Joe Burke, whose habit of sending out resumes for jobs in other cities doesn't exactly suggest an inspiring dedication to Springfield's school kids; as mayor, Sarno will become de facto chair of the School Committee.

Candidate Sarno also called for the resignation of Police Commissioner Ed Flynn after it came out that Flynn, after 19 months on the job, was a finalist for the police chief job in Milwaukee. Until and unless Flynn is offered that job or another (and the commissioner says he hasn't been looking elsewhere), Sarno will have to tackle the centerpiece issue of his campaign—public safety—with a strained relationship with his top cop.

Meanwhile, Sarno will undoubtedly face the heat of former Council colleagues and other aspirants who want the mayor's job for themselves and are already looking forward to November, 2009.

mturner@valleyadvocate.com