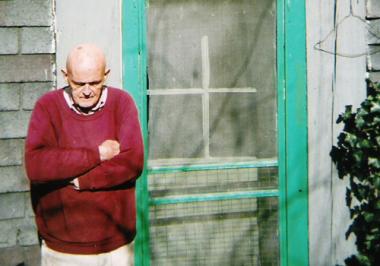

After a year of national misrule and global misery, I badly needed to end 2007 on an up beat. I found that grace note through sculptor Bill Kent (pictured), whom one art critic has called "the greatest living carver of wood in the world." I am honored to call him a friend.

Last April, while working on one of his most original works, a 4-foot-long "torpedo fish," the 87-year-old Kent began to experience pain in his lower right leg. He continued to work until the pain was debilitating. "Peripheral vascular disease," the doctor said; it was "untreatable." Kent the sculptor was sculpted by surgeons at Meriden's MidState Hospital; the leg was amputated just above the knee. Kent now gets around in a wheelchair and with the aid of a prosthetic leg he's dubbed "the Monster."

I have never known anyone like Bill Kent, and I doubt there are many who could equal his pure devotion to artistic creation. Since 1964, he has lived alone and worked out of a converted barn in Durham, Conn. After he got out of the hospital, he returned to this haven to ponder the next hurdle: getting back to work. His work in progress still sat atop his work bench. His sculpting tools were out on his table, like a surgeon's scalpels.

"I want to get back to work but I don't know what's going to happen," he told me at the time. Bill Kent without wood to sculpt, without ideas to ponder, without his piano to play (he graduated from the Yale School of Music, where he studied under Paul Hindemith) was unthinkable; rather, it did not bear thinking about.

Concerned friends, my family among them, gathered to welcome Bill back. No friend was more concerned, or caring, than Joan Baer, who has for the past year become his lifeline to the world of art. This week she sent me a message that buoyed my spirits more than anything I've heard this year: "Bill is well and continues to work at least four hours every day. His latest piece is a monumental sculpture called 'Naked Chicken # 2'." She told me that more dealers and collectors have learned of his work and that the Lyman Allyn Museum is planning an exhibition of his political prints—made from 200-pound slabs of slate on which he has carved the images.

It's not as if Bill Kent has gone unrecognized. In the 1950s, he had five separate critically acclaimed one-man shows in New York and was in the Whitney's Biennial show—but what he has accomplished warrants a major retrospective in a major museum.

"Who cares if the New York dealers or critics can't figure it out? Time settles things out in art," he says. Yet he is stung by the neglect. He points to Cezanne, who was 80 before "receiving any real attention," or Blake, about whom even now art historians are at a loss. And yet, with his hands slowed by his medical problems, the need for recognition is palpable.

Until now, Kent's best revenge has been to keep working. Like a monk on a mission, for the past 40 years he has risen each morning at 4:30, walked the few dozen feet from his quarters to his barn, worked for five hours, broken for lunch, played the piano, then returned to the wood, hammering, chiseling, sanding and, when it was time to stop, planning his next day's goal. This was seven days a week, 365 days a year. That he has rescued at least half of that prodigious schedule is something close to a Christmas miracle for me.

Longtime New Haven curator Johnes Ruta was present at Bill's homecoming. "His is a young man's vision, and you look at Bill and he's 87," said Ruta, who curates shows at the New Haven Public Library and venues in Branford and Bridgeport. "Yet he's one of the youngest people I know. How do you account for this? Maybe art just keeps you young, keeps you going. Look at Merce Cunningham or Martha Graham. I put Bill up there with them, an 87-year-old young man."